Charles Schulz didn’t just draw a comic strip. He basically mapped out the entire human psyche using a round-headed kid and a beagle. If you’re looking for pictures of the peanuts characters, you probably know that feeling. It's a mix of nostalgia and that weirdly specific comfort that comes from seeing Charlie Brown fail to kick a football for the thousandth time.

But here’s the thing. Not all Peanuts art is created equal.

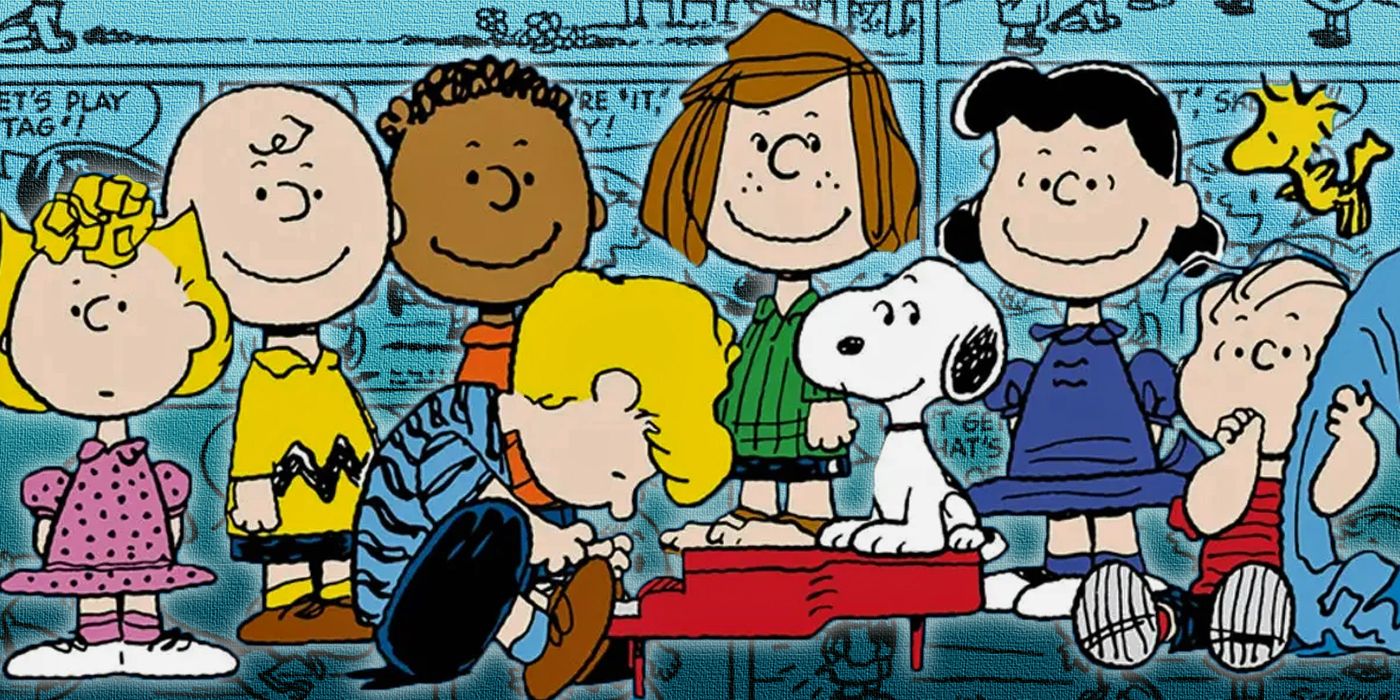

The internet is flooded with generic, polished 3D renders from the recent movies or soulless clip art used for birthday invitations. Honestly, if you want the real soul of the gang, you have to look at how the line work changed from 1950 to 1999. There is a massive difference between the "pudgy" Charlie Brown of the early fifties and the sleek, minimalist version we saw in the eighties.

The Evolution of the Line

Early pictures of the peanuts characters look almost nothing like what we see on Hallmark cards today. In the early 1950s, Snoopy actually looked like a dog. He walked on four legs. His nose was pointier. Charlie Brown’s head was more of an oval than a perfect circle. Schulz was still finding his voice, and the ink was heavy.

By the mid-1960s, everything clicked. This is what collectors call the "Golden Era." This is when Snoopy started walking on two legs and developed that iconic "Joe Cool" smirk. The lines became confident. Schulz had this way of drawing a simple slumped shoulder that conveyed more depression and hope than a thousand-page novel. If you're looking for high-quality images to frame or study, this 1960s-1970s window is where the magic lives.

Schulz famously had a "tremor" in his later years. You can see it in the art from the 1990s. The lines are shaky. Some people find it hard to look at, but for die-hard fans, those pictures are the most intimate. It’s the hand of the master refusing to let go of his pens.

Why the Sunday Strips Are Different

Most people search for Peanuts images and find the daily four-panel strips. They're great. They're punchy. But the Sunday strips? That’s where the artistry peaks. Because Sunday papers allowed for color, Schulz got to experiment with mood.

💡 You might also like: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

Think about the silhouettes.

One of the most iconic pictures of the peanuts characters isn't a close-up of a face; it’s Charlie Brown and Linus leaning against that brick wall, seen from behind. The wall is just a cross-hatched rectangle. The characters are simple shapes. Yet, you know exactly what they’re feeling. You've been there.

The Snoopy Effect

Snoopy hijacked the strip. It’s a known fact. Initially, he was just a silent observer, but once he climbed on top of that doghouse, the visual language of the strip shifted. The doghouse is a masterpiece of perspective—or lack thereof. We almost always see it from the side. It’s a flat plane that acts as a stage.

When you’re sourcing images of Snoopy, pay attention to his ears. Schulz used those ears like a second pair of hands. They defy gravity. They fly. They droop. They show surprise. It’s a masterclass in "squash and stretch" principles used in animation, but applied to a static comic frame.

Licensing and the "Clean" Look Problem

If you go to a big-box store today, you’ll see Peanuts merchandise everywhere. The images are crisp. The colors are bold. But something is usually missing.

Most modern pictures of the peanuts characters used in commercial licensing are "cleaned up" by digital artists. They take Schulz’s original drawings and vectorize them. They smooth out the "jitter." They make the lines perfectly uniform.

📖 Related: Brokeback Mountain Gay Scene: What Most People Get Wrong

It loses the humanity.

Real Peanuts art has "ink bleed." It has tiny imperfections where the nib of the pen caught on the paper. If you’re a creator or a fan looking for authentic visuals, seek out scans of the original newspaper proofs rather than modern digital recreations. The Museum of Fine Arts or the Charles M. Schulz Museum archives are the gold standard for this. You want to see the white-out. You want to see the pencil marks underneath the ink.

The Psychology of the Background (Or Lack Thereof)

Schulz was a minimalist. He rarely drew a horizon line. He almost never drew a house unless it was necessary for the plot. Usually, it’s just a character and a floating prop—a baseball glove, a piano, or a psychiatric booth.

This is why pictures of the peanuts characters work so well as icons or avatars. They aren't tethered to a specific "place." They exist in a void of childhood. This lack of background is a deliberate choice that forces the eye to focus on the emotional state of the character.

- Lucy: Usually drawn with her mouth wide open—a "D" shape that takes up half her face.

- Linus: Always slightly tilted toward his blanket, creating a sense of literal "lean" or dependency.

- Schroeder: Defined by the toy piano, which Schulz drew with intense technical accuracy despite it being a gag.

Where to Find High-Resolution Peanuts Art

Don't just use a basic image search. Most of those results are low-resolution thumbnails or weird fan art that gets the proportions wrong.

- The Charles M. Schulz Museum Digital Exhibits: They host high-resolution scans of original strips. This is the only way to see the actual texture of the paper Schulz used.

- Heritage Auctions: Believe it or not, auction sites are a goldmine. When original 1950s strips go up for sale, they post incredibly detailed photos. You can see the individual strokes of the brush used for Snoopy’s black fur.

- GoComics: They hold the digital distribution rights. It’s the best place for daily strips, though they are the "colored" versions which weren't always Schulz's original intent.

The Color Palette of 1960s TV Specials

We can't talk about images of these characters without mentioning A Charlie Brown Christmas or The Great Pumpkin. The art direction here, led by Bill Melendez and Lee Mendelson, is distinct from the strip.

👉 See also: British TV Show in Department Store: What Most People Get Wrong

The backgrounds in the specials are painterly. They look like watercolors. This creates a beautiful contrast with the flat, boldly outlined characters. If you want a "cozy" aesthetic, images from the 1965-1975 animated specials are the way to go. The colors are slightly muted—lots of deep purples, oranges, and blues—that capture a specific mid-century vibe.

Avoiding Common Misconceptions

People often think the Peanuts characters are "cute."

Schulz hated that.

He once said that there is no humor in happiness. The best pictures of the peanuts characters are actually quite dark or melancholic. Look at Charlie Brown sitting alone on a bench with a lunch bag. Look at the "lonely tree" visuals. When you are selecting images for a project or for your own collection, the ones that resonate most are usually the ones where the characters are dealing with some form of rejection or existential dread. That’s the "Peanuts" brand.

Actionable Steps for Collectors and Fans

If you're looking to use or collect these images, here's how to do it right:

- Prioritize Line Weight: Look for images where the line varies in thickness. If the line is the same width all the way around Charlie Brown's head, it's a cheap digital trace, not an original.

- Check the Signature: Schulz signed his name "Schulz" (no 't'). He always signed it within the panel, often integrated into the grass or the ground.

- Source the Year: Always try to find the date of the strip. A 1955 Snoopy and a 1985 Snoopy are different characters visually. Knowing the timeline helps you curate a consistent "look."

- Respect the Copyright: Peanuts Worldwide LLC is famously protective. If you're using images for anything other than personal enjoyment, make sure you understand the fair use vs. licensing boundaries.

The best way to appreciate the visual history of Peanuts is to stop looking at them as "cartoons" and start looking at them as "drawings." Every loop in Pigpen’s dust cloud was a choice. Every strand of hair on Peppermint Patty’s head was a deliberate stroke. When you find the right pictures of the peanuts characters, you’re not just looking at a brand; you’re looking at fifty years of one man’s internal life laid bare on paper.

Find a high-resolution scan of a 1960s Sunday strip. Zoom in until you can see the grain of the paper. Look at the way the black ink sits on top of the page. That's where the real Peanuts lives—in the physical act of creation.