You’ve seen them. Those neon-streaked stock photos of a runner blurred into a smear of blue light, or maybe that one classic shot of a roller coaster plunging down a 45-degree drop. Most people searching for pictures for kinetic energy are looking for a shortcut to explain motion, but honestly, most of the images you find online are kinda lying to you. They show "speed," sure. But kinetic energy isn't just speed. It’s a relationship between how heavy something is and how fast it’s hauling itself through space.

If you’re a teacher or a student trying to visualize $E_k = \frac{1}{2}mv^2$, a blurry photo of a Ferrari doesn't actually tell the whole story. You need to see the "mass" part of the equation too.

✨ Don't miss: Antimatter: Why the Most Valuable Thing Ever Costs 62 Trillion Dollars

The Visual Lie: Why "Blurry" Doesn't Always Mean Energy

Most pictures for kinetic energy rely on motion blur. It’s a photography trick. You keep the shutter open a fraction of a second longer, and suddenly a walking toddler looks like The Flash. But in the real world of physics—the kind of stuff NASA engineers or structural researchers like those at MIT deal with—kinetic energy is more about the potential for impact.

Think about a bowling ball and a ping-pong ball. If they’re both moving at the same speed, a photo makes them look identical in terms of "action." However, the bowling ball has vastly more kinetic energy because of its mass. This is where most visual aids fail. They ignore the weight.

To really "see" kinetic energy in an image, you shouldn't just look for speed lines. You should look for the consequences of that motion. Look for the bow wave of a massive cargo ship. Look for the way a literal ton of water deforms when it hits a pier. That’s the energy actually doing something.

Why Mass is the Secret Character in Kinetic Energy Photos

Let’s get technical for a second, but keep it simple. If you double the mass of an object, you double its kinetic energy. Simple. But if you double the speed, you quadruple the energy. This is why a picture of a bullet—which weighs almost nothing but travels incredibly fast—is such a common go-to for pictures for kinetic energy.

High-speed photography is probably the best way to actually "see" this concept. When you look at Harold Edgerton’s famous photographs from the mid-20th century—like the bullet piercing the apple—you aren't just seeing a cool trick. You’re seeing the precise moment that kinetic energy is transferred into work (breaking the apple fibers).

The Roller Coaster Trap

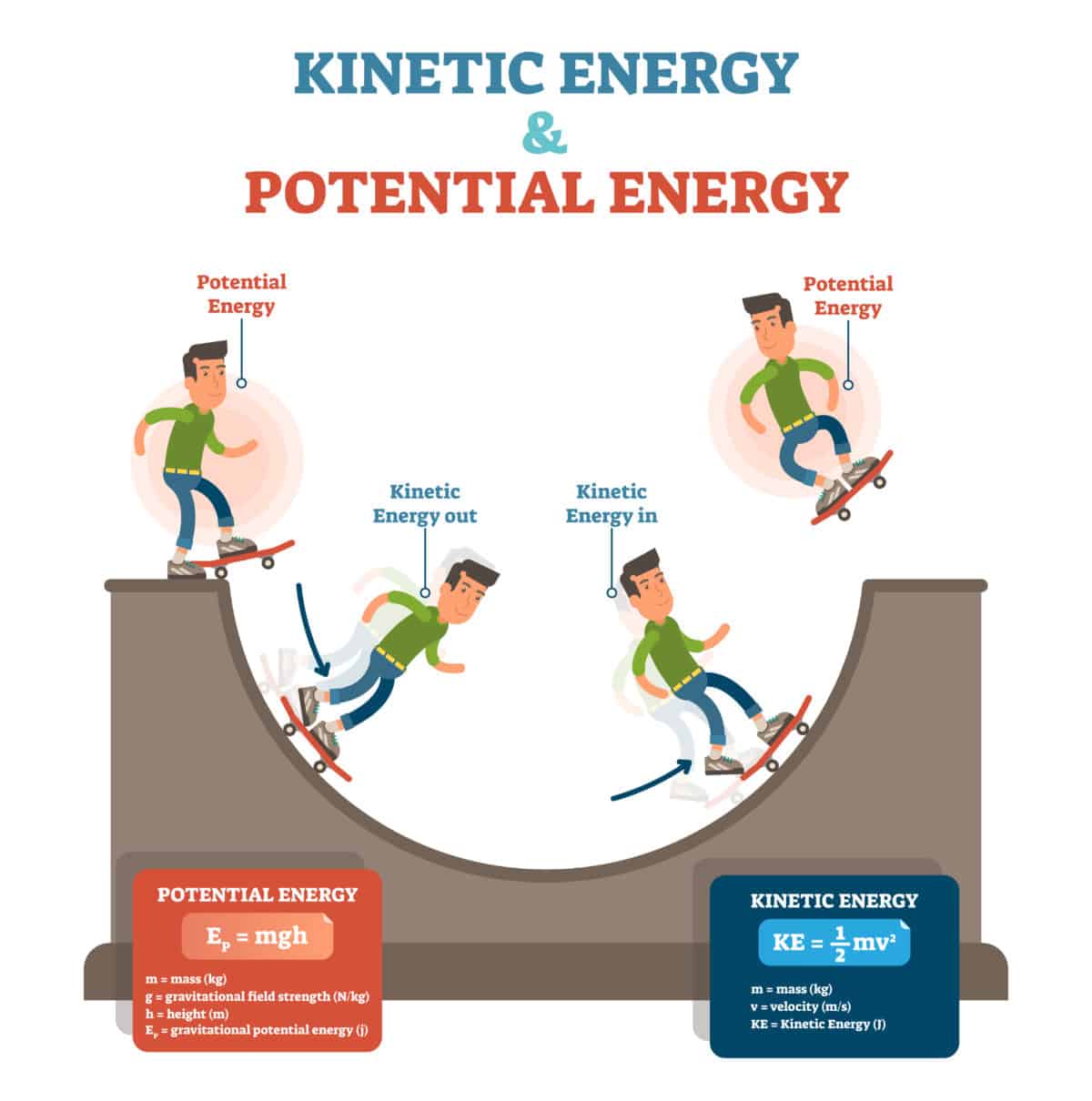

Every textbook uses them. The roller coaster at the top of the hill is "potential," and the one at the bottom is "kinetic." It’s a bit of a cliché, isn't it?

The problem is that these pictures usually feel static. To find a truly effective visual, you need to see the vibration of the tracks or the wind whipping the riders' hair. Real energy is messy. It’s loud. Static photos of coasters often feel like they’re stuck in a vacuum, which is exactly where physics problems happen, but not where real life happens.

Finding Better Pictures for Kinetic Energy in Everyday Life

You don't need a lab. You don't need a million-dollar camera. Honestly, some of the best examples are right in your driveway or at the local park.

- The Pendulum: A wrecking ball at a construction site is the ultimate mass-meets-velocity visual. When it's swinging, that's pure, terrifying kinetic energy.

- Weather Events: A photo of a hurricane isn't just a weather map. It’s a visualization of trillions of joules of kinetic energy in the form of moving air and water.

- Sports: A shot of a linebacker mid-tackle is better than a shot of a sprinter. Why? Because you can see the "m" (mass) and the "v" (velocity) colliding.

If you're scouring Unsplash or Pexels for pictures for kinetic energy, stop typing "energy." Start typing "collision," "impact," or "momentum." You’ll find much more visceral images that actually explain the science without needing a caption.

The Math Behind the Imagery

It’s easy to forget that these photos represent a hard mathematical reality. When we look at a car crash test photo, we are looking at the $v^2$ part of the equation. Because velocity is squared, the damage (the work done by the energy) increases exponentially with speed.

A car hitting a wall at 60 mph isn't twice as bad as one hitting at 30 mph. It’s four times as bad. Visuals that show crumpled metal are the most "honest" pictures for kinetic energy because they show the energy being used up. Energy cannot be destroyed, only transformed. In a crash photo, you're seeing kinetic energy transform into heat, sound, and the deformation of steel.

How to Select Photos for Educational Projects

If you’re building a presentation and need pictures for kinetic energy, follow these rules. Don't just grab the first glowing lightbulb you see—that's electrical or thermal energy, not kinetic.

First, look for scale. A train moving slowly has more kinetic energy than a bird flying fast. Find an image that captures that sense of scale. Second, look for the "before and after." The best way to represent energy is to show what it does to the environment. Dust kicking up behind a desert racer? Perfect. That’s energy being transferred to the ground.

Common Misconceptions in Visuals

Avoid anything with "lightning" or "plasma balls" unless you are specifically talking about the kinetic energy of particles (which is basically what temperature is). For general physics, these are usually distracting.

Also, skip the "battery" icons. It sounds obvious, but a lot of AI-generated imagery for "energy" defaults to green batteries or glowing leaves. That has nothing to do with the physics of motion.

Actionable Steps for Using Kinetic Energy Visuals

To make the most of your visual search, change your strategy from looking for "energy" to looking for "force."

- Look for Displacement: Find photos where an object has clearly moved something else (like a foot kicking a ball).

- Prioritize Realism: Use photos of real objects, like a river flowing or a windmill spinning, rather than abstract 3D renders. Abstract renders often lose the sense of "mass" that is vital for understanding.

- Check the Context: Ensure the image shows something in an active state of motion. A parked plane has zero kinetic energy, no matter how fast it can go.

- Use High-Speed Stills: Search for "strobe photography" or "high-speed capture" to find images that freeze a moment in time, showing the exact point where kinetic energy is at its peak.

When you stop looking for "concept art" and start looking for "consequences of motion," your collection of pictures for kinetic energy will actually start making sense to whoever is looking at them. Focus on the weight, the speed, and the impact. That’s where the real science lives.