You’re probably here because of a crumpled homework assignment or a DIY project that’s suddenly gone sideways. Geometry has this funny way of feeling like common sense until you actually have to put pen to paper. Honestly, most of us just remember "base times height," but then we stare at a scalene triangle with no right angles and realize that old middle school formula feels about as useful as a screen door on a submarine.

Understanding how to find area on triangle isn't just about memorizing a string of letters like $A = \frac{1}{2}bh$. It’s about seeing the relationship between shapes. If you can find the area of a rectangle, you can find the area of a triangle. Why? Because every triangle is basically just half of a parallelogram. That’s the "aha!" moment most people miss.

The Foundation: Why One-Half Matters

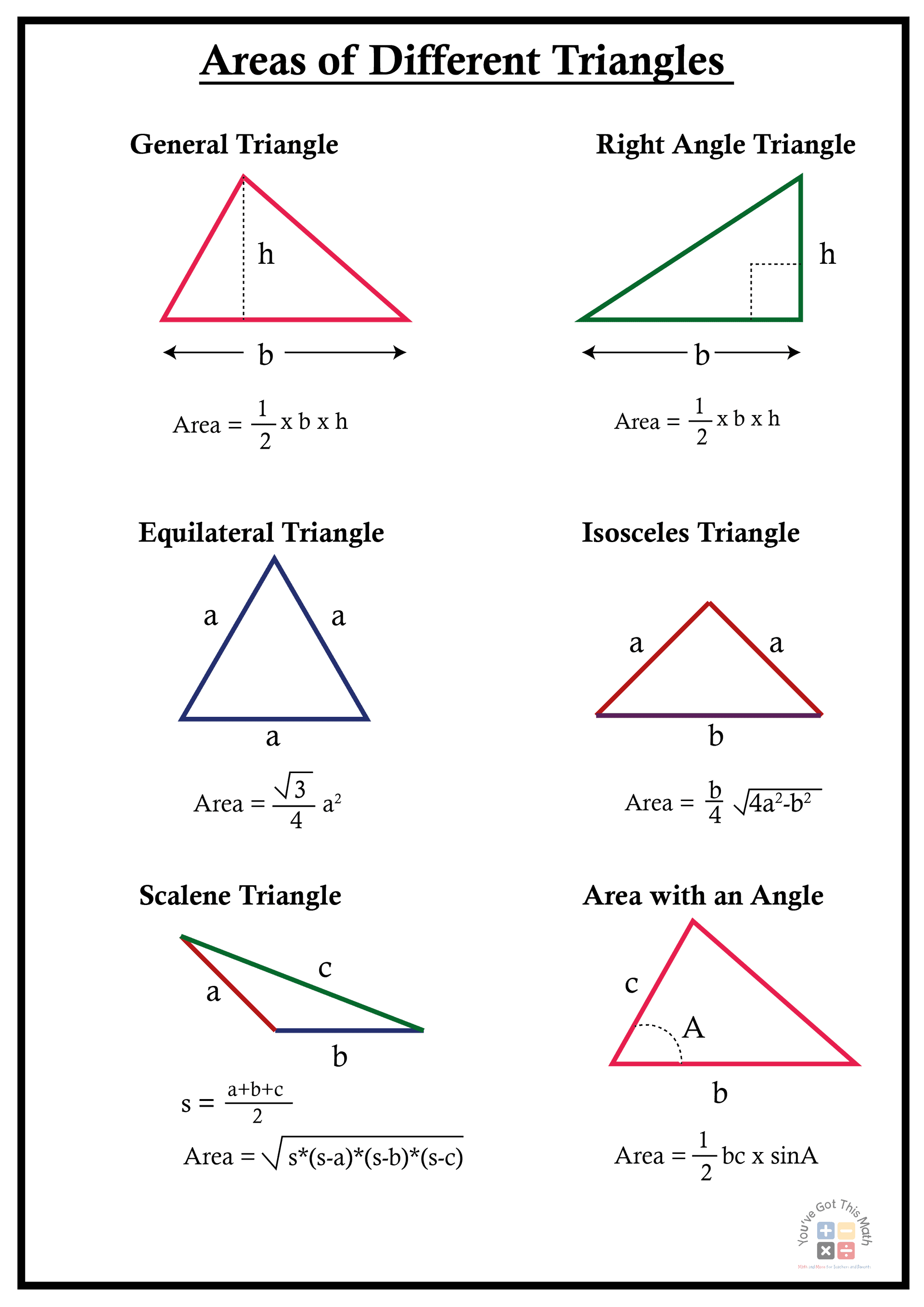

Let’s start with the classic. You have a base. You have a height. The formula $Area = \frac{1}{2} \times base \times height$ is the gold standard. But here is where it gets tricky: people constantly pick the wrong numbers for the "height."

In a right-angled triangle, it’s easy. The two sides forming the L-shape are your base and height. Simple. But what if the triangle is leaning? Or what if it looks like a mountain peak? The height must be the perpendicular line from the top point (the vertex) down to the base. It’s the altitude. If you use the length of a slanted side instead of the vertical height, your calculation is going to be wrong every single time.

Think of it like measuring your own height. You don't measure along your spine if you're leaning over; you measure straight up from the floor.

When You Don't Have the Height: Enter Heron’s Formula

Sometimes, life doesn't give you a nice, straight vertical line. You might just have a triangle where you know all three side lengths, but you have no clue what the altitude is. This is where Heron of Alexandria comes in. He was a Greek mathematician and engineer who lived around 10–70 AD, and he came up with a way to calculate area using only the sides.

It’s a bit more "mathy," but it’s a lifesaver for real-world measurements, like measuring a triangular patch of garden.

First, you find the semi-perimeter ($s$). You just add all the sides ($a$, $b$, and $c$) together and divide by two.

$$s = \frac{a + b + c}{2}$$

Once you have that $s$ value, you plug it into this:

👉 See also: Tommy Hilfiger: What Most People Get Wrong About the King of Prep

$$Area = \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}$$

It looks intimidating. I get it. But it’s just subtraction and multiplication. If your sides are 5, 6, and 7, your $s$ is 9. Then you’re just doing $9 \times 4 \times 3 \times 2$, then taking the square root. It works perfectly every time without ever needing a protractor or a level.

The Trigonometry Shortcut (SAS Method)

Maybe you're in a trig class, or maybe you're a woodworker with a fancy digital angle finder. If you know two sides and the angle between them (Side-Angle-Side), you don't need to go hunting for the height.

The formula uses the sine function:

$$Area = \frac{1}{2}ab \sin(C)$$

Essentially, the $\sin(C)$ part of the equation is doing the hard work of "creating" a virtual height for you. It’s elegant. If you have a triangle where two sides are 10cm and 12cm, and the angle between them is 30 degrees, the area is just $0.5 \times 10 \times 12 \times 0.5$ (since $\sin(30)$ is $0.5$). That's 30 square centimeters. Done.

Equilateral Triangles: The Specialist’s Route

If all three sides are exactly the same length, you could use Heron's formula, but that’s like using a sledgehammer to hang a picture frame. There is a faster way. Because an equilateral triangle is perfectly symmetrical, the math collapses into a very specific shortcut:

$$Area = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{4} \times side^2$$

If you’re working with a side of 4, you just square it (16), divide by 4 (getting 4), and multiply by $\sqrt{3}$ (about 1.73). It’s roughly 6.92. This is incredibly useful for tilers or designers working with geometric patterns where every piece is identical.

Why This Matters in the Real World

You might think how to find area on triangle is just for textbooks. It’s not.

I once watched a friend try to buy sod for a triangular corner of his backyard. He guessed. He ended up with about 40% too much grass because he forgot the "one-half" part of the equation. He treated the triangle like a rectangle. That’s a literal waste of money.

💡 You might also like: She’s a Cowboy Killer: Why This Viral Aesthetic is Taking Over Your Feed

Architects use these calculations to determine wind loads on gabled roofs. Civil engineers use them to calculate the stresses on bridge trusses. Even in computer graphics, every 3D model you see in a video game—from Mario to the hyper-realistic characters in The Last of Us—is made up of millions of tiny triangles. The computer is constantly calculating their area and orientation to render light and shadow.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Units of Measurement: This is the silent killer. If one side is in inches and the other is in feet, your area will be total nonsense. Convert everything to the same unit before you start multiplying.

- The "Slant" Trap: Never, ever use the slanted side of a non-right triangle as your height. It's the most frequent mistake in geometry.

- Rounding Too Early: If you’re using Heron’s formula or trig, keep those decimal points until the very end. Rounding $s$ or $\sin(C)$ too early can throw your final answer off by several whole units.

Actionable Steps for Success

- Identify what you know. Do you have a height? If yes, use $\frac{1}{2}bh$. Do you only have side lengths? Use Heron's.

- Sketch it out. Even a bad drawing helps you visualize which side is the base and where the height should drop.

- Check the angle. If there’s a square symbol in the corner, it’s a right triangle. Your life just got 10x easier—the two sides touching that square are your base and height.

- Double-check your units. Ensure you’re looking at square inches, square meters, or square miles. Area is always squared.

Finding the area isn't about being a math genius; it's about picking the right tool for the specific shape in front of you. Once you stop fearing the formulas, the shapes start making sense.