If you pull up a basic digital layout and look for the Appalachian Mountains on the map, you’ll probably see a jagged green smudge stretching from Alabama up toward Canada. It looks manageable. It looks like a weekend drive. Honestly, that’s the first mistake most people make because the scale of this range is absolutely massive, and its "map footprint" is more of a geological puzzle than a single line of peaks.

They’re old. Like, really old. We are talking about 480 million years of history. When these mountains first pushed upward during the Ordovician Period, they were likely as tall as the Himalayas are today. Time, rain, and ice ground them down into the rolling, blue-misted ridges we see now. But don't let the soft edges fool you. The "Appalachians" aren't just one mountain range; they’re a collection of distinct provinces that make mapping them a nightmare for cartographers who want simplicity.

💡 You might also like: The Crazy Horse Memorial Gift Shop: Where to Find Real Art in a World of Plastic Souvenirs

Where the Lines Actually Fall

Mapping the Appalachians is tricky because the "geological" map doesn't always match the "cultural" map. If you’re looking at a standard physical map, you’ll see the chain starts down in northern Alabama and Georgia. It then snakes through Tennessee and North Carolina—home to the Great Smokies—before narrowing through the Virginias and Maryland.

Then it gets weird.

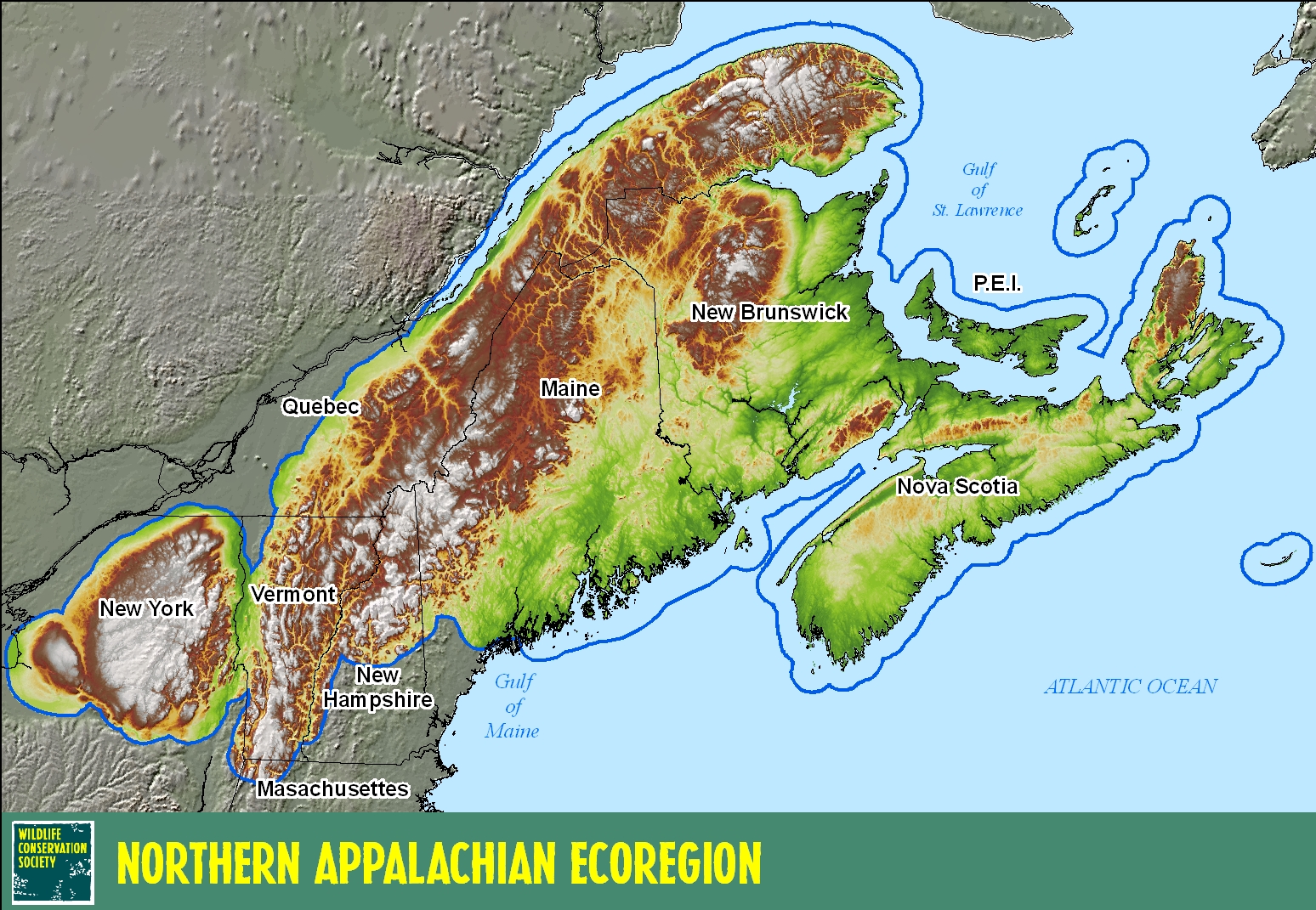

Once you hit Pennsylvania, the mountains sort of shatter into the Ridge-and-Valley province. You've seen this from a plane window, right? Those long, parallel lines that look like a giant took a rake to the earth? That’s the heart of the chain. From there, it heads into the Catskills in New York, the Green Mountains of Vermont, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. It finally "ends" at Mount Katahdin in Maine, at least for the hikers. Geologically? It keeps going into Canada, appearing as the Long Range Mountains in Newfoundland. Some geologists, like those at the United States Geological Survey (USGS), even argue that parts of the Scottish Highlands and the Little Atlas in Morocco are technically part of the same ancient chain from back when Pangea was a thing.

The Secret Provinces Most Maps Skip

Most people just see one big lump of green. But if you want to understand the Appalachian Mountains on the map like an expert, you have to look at the three distinct layers.

First, there’s the Blue Ridge. This is the "pretty" part people put on postcards. It’s a narrow strip of igneous and metamorphic rock. It’s where you find the highest peak in the eastern U.S., Mount Mitchell, standing at 6,684 feet. If you’re looking at a map of North Carolina, this is the spine.

To the west of that is the Ridge and Valley province. This is where the folding happened. It’s a series of sandstone ridges and limestone valleys. It’s why the roads in West Virginia are so curvy. You can't just drive straight; you’re trapped by the geometry of the earth.

Finally, there’s the Appalachian Plateau. This is the rugged, dissected highland to the far west. It includes the Alleghenies and the Cumberland Plateau. On a map, this looks less like "peaks" and more like a high table that’s been eroded by a million tiny streams. It covers a huge chunk of Kentucky and West Virginia. Honestly, if you live in Pittsburgh, you’re technically on the Appalachian Plateau, even if it feels like a city of hills rather than a "mountain range."

Why the Human Map is Different

There is a huge difference between the geological boundary and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) map. The ARC is a federal-state partnership, and their map is based on economics and sociology.

Their map includes 423 counties across 13 states.

Interestingly, the ARC map includes parts of Mississippi and Ohio that no geologist would ever call "mountainous." Why? Because the "Appalachian" identity is tied to the coal industry, timber, and specific rural challenges. So, when you search for the Appalachian Mountains on the map, you have to ask yourself: am I looking for rocks, or am I looking for people?

The cultural map is much wider than the physical one. It’s a region defined by resilience and a specific type of folklore that doesn't care where the sandstone ends.

Surprising Spots You Didn't Know Were Appalachian

You probably think of Virginia or Tennessee. But did you know the mountains technically clip the corner of New Jersey? The Kittatinny Mountains are part of the ridge-and-valley section. Even parts of Alabama that feel like "the deep south" are fundamentally shaped by the tail end of this range.

- Birmingham, Alabama: Sits right at the foot of the southern Appalachians. The iron ore found in those mountains is the whole reason the city exists.

- The Hudson Valley: The mountains basically form the walls of this iconic New York landscape.

- Belle Isle, Newfoundland: This is the rugged, lonely northern terminus where the mountains finally sink into the Atlantic.

The Evolution of the Map

Back in the 1700s, maps of this area were wildly inaccurate. Early European explorers called them the "Apalatchen" mountains, borrowing the name from the Apalachee tribe in Florida (who didn't even live in the mountains). John Mitchell’s 1755 map—one of the most important in American history—showed them as a massive, almost impenetrable wall. This helped keep the British colonies pinned to the coast for decades.

Today, we use LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging). This technology lets us "see" through the dense forest canopy. What we’ve found is that the Appalachian map is covered in "scars" from ancient landslides and human mining that were invisible just twenty years ago. We are literally re-mapping the range as we speak.

Navigating the Terrain Practically

If you’re planning to visit based on what you see on a map, you need to understand "Appalachian Miles." A mile on a flat map of Kansas is a minute. A mile in the Appalachians is a workout.

The elevation changes are relentless. Because the range is so old, the soil is deep and the forests are thick. In the West, you can see a storm coming from fifty miles away. In the Appalachians, you won't see it until the sky turns gray and the first drop hits your windshield.

What to look for on a high-quality map:

- Contour lines: If they are tightly packed, you’re in the Blue Ridge or the high Alleghenies.

- Gap names: Look for "Wind Gap" or "Water Gap." These are spots where ancient rivers cut through the ridges, and they are almost always where the highways (and historical migration routes) are located.

- National Forest boundaries: The Monongahela, George Washington, and Cherokee National Forests mark the wildest, least-developed sections of the map.

Moving Beyond the Paper

Maps are just representations. To truly "locate" the Appalachians, you have to look at the intersection of biology and geology. This range is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet outside of the tropics. It’s a "refuge" for plants and animals that moved south during the last Ice Age.

The map of the Appalachians is also a map of water. These mountains form the Eastern Continental Divide. Rain falling on one side of a ridge in Virginia goes to the Atlantic; rain on the other side travels all the way to the Gulf of Mexico via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. That’s a massive responsibility for a bunch of "old, small" mountains.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

Stop looking at the whole chain and pick a province. If you want jagged cliffs and high vistas, target the High Peaks of the North Carolina/Tennessee border or the Presidential Range in New Hampshire. If you want deep, misty gorges and incredible whitewater, the Appalachian Plateau in West Virginia (specifically the New River Gorge) is your spot.

Don't trust GPS travel times blindly. Digital maps often struggle with the "verticality" of mountain roads. Add at least 20% to any estimated drive time in the rural parts of the range.

For the most accurate physical representation, use the USGS TopoView tool. It allows you to overlay historical maps with modern satellite imagery. It’s the best way to see how the Appalachian Mountains on the map have "changed" as our technology got better at measuring them.

Check the "Proclamation Line of 1763" on historical maps if you want to understand why these mountains are the reason the United States looks the way it does today. That line, drawn along the crest of the Appalachians, was meant to stop westward expansion—and it was the spark that helped ignite the American Revolution. The map isn't just geography; it's the blueprint of American history.

Key Takeaways for Explorers

- Download Offline Maps: Cell service is a myth in the deep hollers of the Ridge and Valley province.

- Check the Elevation Profile: A 5-mile hike in the Appalachians can involve 3,000 feet of gain. That is not a "stroll."

- Respect the Gaps: When driving, follow the rivers. The gaps are the natural "highways" and usually offer the most scenic (and easiest) transit.

- Study the Forest Service Maps: They provide much more detail on fire roads and trailheads than Google or Apple Maps ever will.

The Appalachians aren't just a place you find on a map; they are a 2,000-mile long physical barrier that shaped the climate, the culture, and the very boundaries of the Eastern United States. Understanding the layers—from the Blue Ridge to the Plateau—is the only way to truly see what you're looking at.