The Appalachians are old. Really old. When you look at an appalachian fault line map, you aren't just looking at a few cracks in the dirt; you're looking at the scars of a literal continental car crash that happened hundreds of millions of years ago. It’s kinda weird to think about. We usually associate earthquakes and massive fault lines with California or the Pacific Northwest, where the ground is constantly reminding everyone who's boss. But the East Coast? It feels solid. Permanent.

Actually, it's a bit of a mess down there.

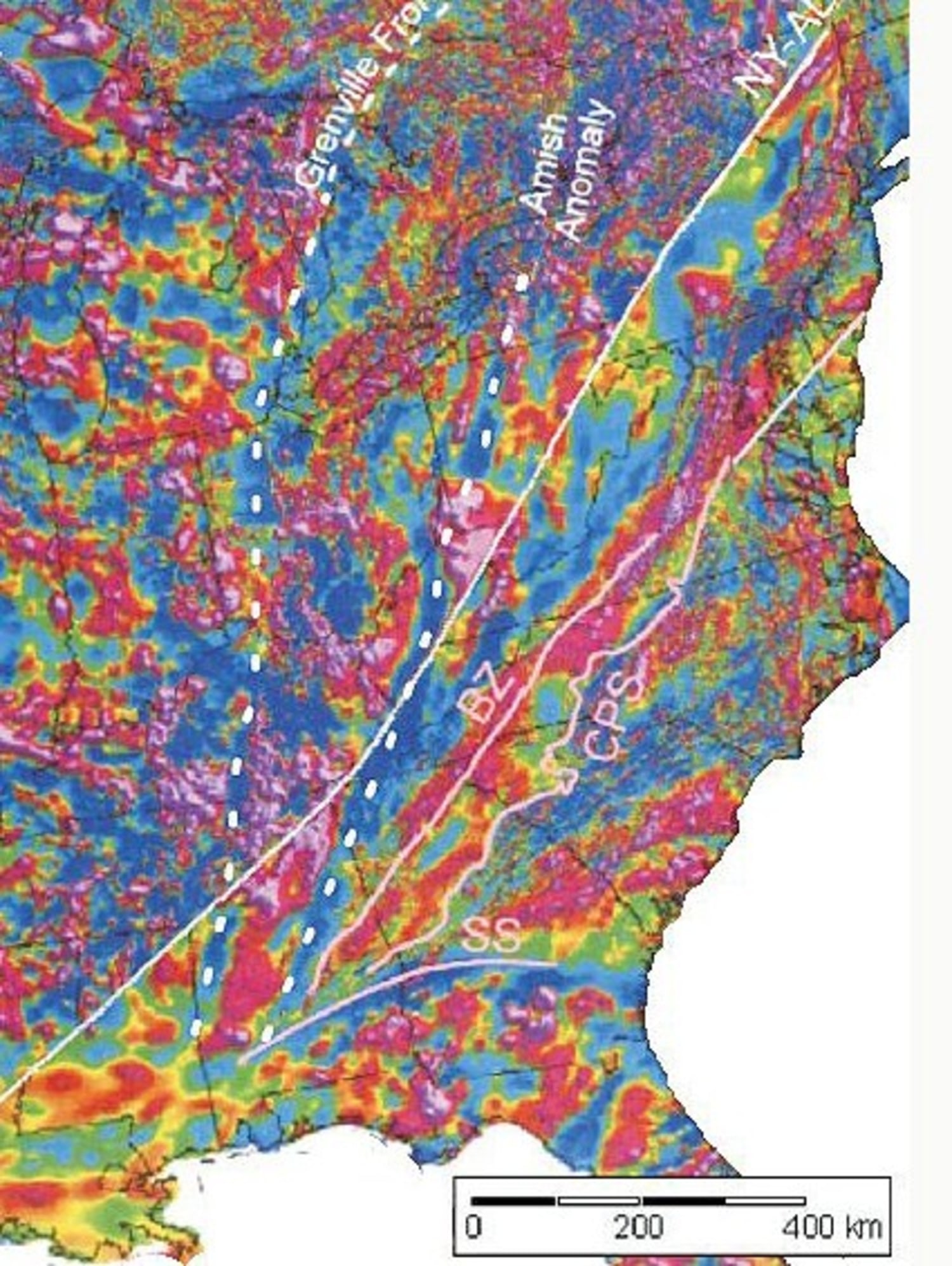

If you’re hunting for a single, clean line like the San Andreas, you’re gonna be disappointed. It doesn't exist. Instead, the Appalachian region is a tangled web of ancient sutures and "blind" faults that don't always show up on the surface. Understanding where these lines are—and why they still matter in 2026—requires a bit of a shift in how we think about geology.

The Reality of the Appalachian Fault Line Map

Most people start their search because they felt a rattle. Maybe it was a small tremor in Virginia or a strange vibration in North Carolina. They want to see the map. They want to see the "red zone."

When you look at a professional appalachian fault line map provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), you’ll notice something immediately: it's crowded. There isn't one line. There are thousands. Most of these are "inactive," meaning they haven't moved since the dinosaurs were walking around. But "inactive" is a tricky word in geology. It basically means "hasn't moved in a while," but the stress of the North American plate drifting westward still puts pressure on these old breaks.

The most famous of these is the Brevard Fault Zone. It runs roughly from Alabama up through the Carolinas and into Virginia. If you’ve ever driven the Blue Ridge Parkway, you’ve probably crossed it a dozen times without realizing it. It’s a massive shear zone. Back when the supercontinent Pangea was forming, Africa literally slammed into North America. That collision crumpled the crust like the hood of a car in a head-on collision. The Brevard Fault is one of the biggest "scars" from that event.

Why the New Madrid Gets All the Press

People often confuse Appalachian faults with the New Madrid Seismic Zone. They aren't the same thing. The New Madrid is out near the Mississippi River and it's scary because it’s active and buried under deep river sediment. Appalachian faults are different. They are mostly in hard, crystalline rock.

Hard rock is a great conductor. Think of it like this: if you hit a piece of wood with a hammer, the vibration stops pretty quick. If you hit a steel rail with a hammer, you can hear it a mile away. Because the Appalachian crust is so old and dense, an earthquake on an Appalachian fault travels way further than one in California.

Remember the 2011 Mineral, Virginia quake? It was a 5.8 magnitude. In California, that’s a Tuesday. People might not even spill their coffee. But in the East? It was felt from Canada down to Georgia. It cracked the Washington Monument. That’s the power of the Appalachian geology. The appalachian fault line map isn't just a guide to where the ground might break; it's a map of how energy travels through the entire Eastern Seaboard.

The Eastern Piedmont Fault System

If the Brevard Fault is the "celebrity" of the region, the Eastern Piedmont Fault System is the workhorse. This is a collection of faults that runs along the "Fall Line"—that transition point where the hard rocks of the mountains meet the soft sands of the coastal plain.

Cities like Richmond, Raleigh, and Columbia sit right near this transition.

Geologists like Dr. Robert Hatcher, who spent decades mapping these structures, have pointed out that these faults are incredibly complex. They aren't just vertical cracks. They are often "thrust faults," where one slab of Earth has been shoved on top of another.

Imagine trying to map a stack of pancakes that someone stepped on. That's what the USGS is dealing with.

- The Ramapo Fault: This one is a big deal for folks in New York and New Jersey. It runs through the Highlands and has been blamed for various small tremors over the years.

- The Central Virginia Seismic Zone: This isn't one single fault line you can point to on a map and say "there it is." It's a localized area of crustal weakness. It’s basically a shattered zone in the bedrock.

- The Giles County Seismic Zone: Located in Southwest Virginia, this area has a history of larger quakes, including a massive one in 1897 that was felt across twelve states.

The "Blind" Danger: Why Maps Are Often Incomplete

Here is the thing that keeps geologists up at night: many of the faults in the Appalachians are "blind."

In the West, a fault often leaves a visible scar on the surface called a fault scarp. You can walk up to it and touch it. In the East, we have rain. We have trees. We have millions of years of erosion and thick forest cover. The ground heals its surface wounds very quickly.

A fault might be lurking three miles underground, totally invisible to someone standing on top of it. We only find them when they move. Or when we use incredibly expensive seismic imaging—basically an ultrasound for the Earth. This means that any appalachian fault line map you find online is, by definition, a work in progress. It’s a best-guess based on the data we have right now.

Honestly, the mapping has improved a lot since 2020. Using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), scientists can now "strip away" the trees from satellite imagery to see the bare ground. They’re finding old fault scarps that nobody knew existed. It turns out the Appalachians are a bit more "broken" than we thought.

The Human Element: Building on the Lines

Should you be worried? Probably not.

The odds of a catastrophic, "movie-style" earthquake in the Appalachians are low. But they aren't zero. The real issue is infrastructure. Because we don't have major quakes every ten years, our building codes historically haven't been as strict as those in San Francisco or Tokyo.

Old brick buildings—the kind that make East Coast downtowns so beautiful—are basically death traps in a significant earthquake. They don't flex. They crumble. When you look at an appalachian fault line map, don't look for where the ground will open up. Look for where the old, unreinforced masonry is located near those zones. That's the real risk.

Mapping the Future of the Mountains

The Appalachian mountains are currently in what's called "isostatic rebound." Basically, because the mountains are eroding and becoming lighter, the Earth's crust is slowly bobbing back up, like a boat after you take a heavy crate off the deck.

This tiny, slow-motion rising puts stress on those ancient fault lines.

Most of the time, this stress is released in tiny pops—earthquakes so small you’d think it was just a heavy truck passing by. But every once in a long while, the stress builds up.

If you're looking at a map for home-buying or just out of curiosity, pay attention to the "Basement Tectonics." The surface soil doesn't matter nearly as much as the "basement" rock—the ancient, hard crust several miles down. That is where the real story of the Appalachian faults is written.

Practical Steps for Residents and Travelers

If you live in or are traveling through the Appalachian corridor, there are a few things you can actually do with this information. Don't just stare at the map and worry.

- Check the USGS Real-Time Map: The USGS maintains a "Latest Earthquakes" map. If you feel something, check it immediately. It’ll tell you the depth and the specific fault zone involved.

- Secure the Heavy Stuff: In the 2011 Virginia quake, most injuries weren't from buildings falling down. They were from bookshelves and TVs falling on people. If you live near a known zone like the Central Virginia or Giles County areas, strap your tall furniture to the wall.

- Understand Your Foundation: If you are building a home in the Appalachians, find out if you are on "fill" or "bedrock." Bedrock is your friend. Soft soil can amplify shaking, making a small quake feel much worse.

- Don't Buy the Hype: You’ll see "prophecy" maps or "disaster" maps online claiming the East Coast is going to split in half. That’s nonsense. Stick to sources like the Virginia Department of Energy or the Geological Surveys of Tennessee and North Carolina.

The Appalachian Mountains are some of the oldest on the planet. They’ve seen continents come together and rip apart. They’ve seen the rise and fall of countless species. A few modern faults aren't going to destroy them, but understanding the appalachian fault line map helps us respect the fact that the ground beneath our feet is a lot more alive than it looks.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way: The Chicago Airport Map Food You Actually Want to Eat

Instead of seeing these fault lines as a threat, think of them as the stitches holding the continent together. They are the history of the world written in stone. If you want to dive deeper, your next move should be looking up the "LiDAR topography" of your specific county. You might be surprised to see the ripples and ridges that don't show up on a standard Google Map, revealing the true, rugged skeleton of the mountains.

Actionable Insights for Property Owners and Enthusiasts:

To get the most accurate picture of your local risk, navigate to the USGS Quaternary Fault and Fold Database. This is the "gold standard" for professional mapping. Unlike a static image, this interactive database allows you to zoom into specific coordinates to see if a fault has been identified in your backyard.

Additionally, if you are in a high-risk masonry area, consider a "seismic retrofit" for your chimney. In the Appalachians, the chimney is often the first thing to go during a moderate tremor. Reinforcing it or ensuring it is properly tied to the house frame is a practical, high-value move that far outweighs the utility of simply staring at a map. Keep your emergency kit updated not just for snowstorms, but for the rare, deep-crust rumble that these ancient mountains occasionally provide.