You’ve seen it a thousand times. That massive green smear across South America. When you look for the Amazon on world map displays, your eyes naturally drift toward Brazil. It’s huge. It’s iconic. But honestly, most of the maps we grew up with are kinda lying to us about the scale and the actual boundaries of this place.

The Amazon isn't just a forest. It’s a liquid heart.

If you look at a standard Mercator projection, the kind hanging in every middle school classroom, the proportions are all wonky. Greenland looks like it could swallow South America whole. In reality, you could fit Greenland into the Amazon Basin about three times. Mapping this region isn't just about drawing lines around trees; it's about understanding a watershed that touches nine different nations.

The Borders No One Talks About

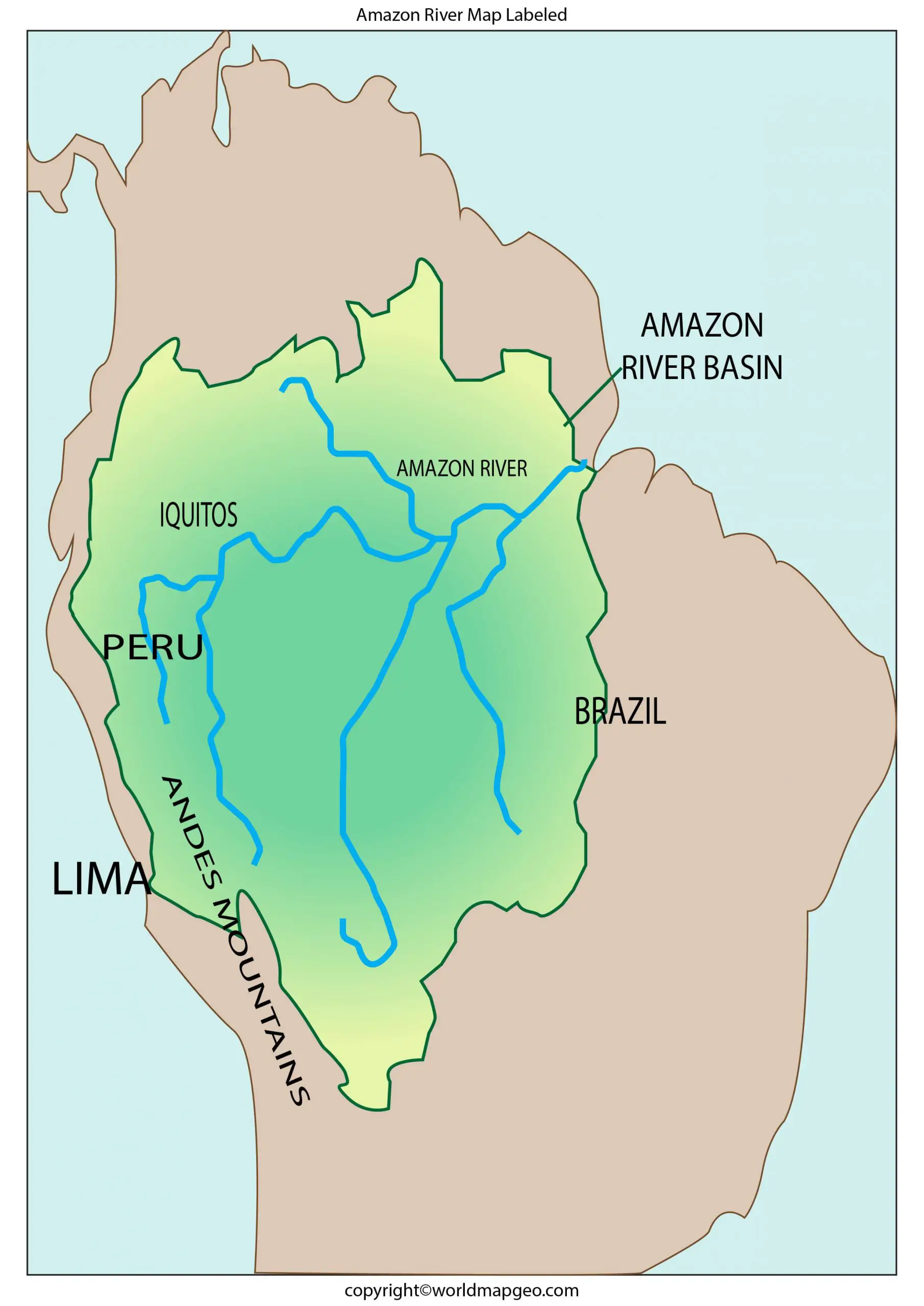

When people search for the Amazon on world map coordinates, they usually think of the "Legal Amazon" in Brazil. That’s a mistake. While Brazil holds about 60% of the rainforest, the biome spills over into Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.

It’s a geopolitical nightmare.

Mapping the Amazon requires looking at three distinct layers: the River, the Forest, and the Basin. They don't always overlap perfectly. The Amazon River itself starts as a tiny glacial stream in the Peruvian Andes—specifically at Nevado Mismi. If you’re looking at a map and don’t see that tiny blue thread starting high in the mountains, you’re missing the point of the whole system.

The Blue Line vs. The Green Mass

Geographers have spent decades arguing over where the river actually begins. For a long time, the Marañón River was the king. Then, researchers like Andrew Johnston from the Smithsonian pointed toward the Apurímac. Why does this matter for a map? Because it changes the length of the river. If you follow the newest data, the Amazon might actually be longer than the Nile.

The Amazon River discharges about 209,000 cubic meters of water into the Atlantic every single second. Think about that. It’s more than the next seven largest rivers combined. On a world map, this looks like a single vein, but it’s actually an inland sea. During the rainy season, the river can widen by thirty miles. It swallows the forest.

The forest, or the "Bioma Amazônia," covers about 6.7 million square kilometers. It’s hard to wrap your head around that number. To put it in perspective, if the Amazon were a country, it would be the ninth-largest in the world.

Why Your Digital Map is Probably Outdated

The Amazon on world map views provided by Google Earth or satellite imagery offer a different, more somber story than the political maps of the 1990s. We’re seeing "fishbone" patterns. These are the marks of roads like the BR-163 or the Trans-Amazonian Highway.

When you zoom in, you see the reality of the "Arc of Deforestation."

Logging and cattle ranching have carved out massive chunks of the southern and eastern edges. This isn't just environmentalist talk; it’s a geographical shift. When the trees go, the "flying rivers" disappear.

✨ Don't miss: SFO to French Polynesia: What Most Travelers Get Wrong About the Flight

The Flying Rivers Phenomenon

You won’t see these on a standard map. "Flying rivers" are massive currents of water vapor that travel through the atmosphere. A single large tree can release 1,000 liters of water into the air per day through evapotranspiration. This moisture travels across the continent, hitting the Andes Mountains and turning south to water the farms in Argentina and Uruguay.

If you map the Amazon without considering the atmosphere, you're only seeing half the picture. The Amazon actually creates its own weather.

The Human Map: Uncontacted Tribes and Urban Jungles

Most people imagine the Amazon as a void. A green blank spot.

That’s a colonial way of looking at a map.

There are roughly 35 million people living in the Amazon. That includes major cities like Manaus, a metropolis of two million people sitting right in the middle of the jungle with an opera house and a massive industrial zone. Mapping the Amazon requires acknowledging the 400+ indigenous groups who have lived there for millennia.

FUNAI, the Brazilian indigenous affairs agency, has identified over 100 "uncontacted" groups. Their territories are often protected by law, but they are under constant pressure. On a digital Amazon on world map layout, these areas are often marked as "Indigenous Territories," but the borders are porous. Gold miners (garimpeiros) and loggers often ignore the lines drawn in Brasília.

The Hidden Cities of the Past

Recent LiDAR technology (Light Detection and Ranging) has completely flipped our historical maps upside down. Researchers like Heiko Prümers have found evidence of complex urban centers in the Llanos de Mojos of Bolivia.

We used to think the Amazon was "untouched" wilderness.

✨ Don't miss: The Las Vegas 24 Hour Buffet Pass: Is This Still a Real Thing?

We were wrong.

The maps are now being rewritten to show "garden cities," causeways, and canals that supported thousands of people long before Europeans arrived. The Amazon on world map history is actually a map of an ancient, managed landscape.

How to Actually "See" the Amazon Today

If you want to view the Amazon accurately, you need to look past the green polygons. Use tools that show real-time data.

- Global Forest Watch: This uses satellite imagery to show near real-time forest loss. It’s depressing but necessary.

- RAISG (Amazon Geo-Referenced Socio-Environmental Information Network): This is a consortium of experts from across South America. They provide the most accurate maps of indigenous lands and protected areas.

- NASA’s FIRMS: If you want to see the "fire season," this map shows thermal signatures in real-time.

Mapping the Amazon isn't a "set it and forget it" task. It's a living, breathing, and unfortunately shrinking entity. The maps from ten years ago are basically ancient history.

The Andes Connection

You can’t understand the Amazon on a world map without looking at the mountains to the west. The Andes act as a giant wall. When the trade winds blow moisture from the Atlantic across the basin, it hits the Andes and falls as rain. This runoff carries nutrients—sediment—down into the lowlands.

This is why we have "White Water" rivers and "Black Water" rivers.

The Rio Negro is black because of decomposed leaf matter (tannins). The Amazon main stem is "white" (actually muddy brown) because of Andean silt. On a high-resolution map, the "Meeting of the Waters" near Manaus is a stark line where these two colors run side-by-side without mixing for miles. It’s one of the few geographical features you can see clearly from space that isn't a mountain or a coastline.

The Geopolitical Struggle for the Map

Every country with a piece of the Amazon treats it differently.

Ecuador and Peru have to balance oil extraction with conservation. Colombia is trying to manage its "Amazonian heart" after decades of internal conflict that actually, ironically, kept some parts of the forest "protected" because people were too afraid to go there. Brazil’s policy shifts with every election, moving from strict protection to aggressive development and back again.

When you look at the Amazon on world map borders, you’re looking at a site of intense political friction. It’s a resource. It’s a carbon sink. It’s a home. It’s a sovereign territory.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Amazon Data

If you are researching the Amazon for travel, education, or investment, don't rely on a single source. The scale is too vast for one perspective.

- Check the Seasonality: Always look at "flooded forest" (Várzea) maps. If you visit the Amazon during the high-water season (May-July), the geography is totally different than the dry season (September-November).

- Verify the Source: Maps produced by mining interests will look very different from those produced by NGOs like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

- Acknowledge the Basin: Don't just look for "The Amazon." Search for the "Amazon Basin" to see the full drainage area. This includes parts of the map you’d never expect, reaching almost to the Caribbean coast.

- Use 3D Visualizations: To understand the "Flying Rivers," use atmospheric maps like those from the NOAA or Windy.com.

The Amazon is the world’s most complex puzzle. It’s a place where the map is constantly being redrawn—sometimes by nature, sometimes by a chainsaw, and sometimes by a scientist with a laser.

Understanding where the Amazon on world map coordinates sit is just the start. The real challenge is understanding how all those pieces—the water, the trees, the people, and the mountains—fit together to keep the rest of the planet breathing. It’s not just a place in South America. It’s a global utility.

Next time you open a map, look for the rivers that feed it from the Andes. Look for the way it touches the Atlantic. Don't see it as a green blob. See it as a giant, pulsing pump that moves water across an entire hemisphere. That’s the version of the map that actually matters.

To get the most accurate view of current conditions, cross-reference the MapBiomas project data with the Inpe (Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research) daily satellite feeds. These sources provide the raw, unfiltered geographical reality of the region as it exists this year, rather than the idealized versions found in older atlases. Use these tools to track forest cover changes and indigenous land boundaries with precision.