If you try to find Tenochtitlan on a map today, you’re basically looking for a ghost. You'll see the sprawling, high-altitude chaos of Mexico City instead. Most people think the old Aztec capital was just "under" the modern streets, like a basement, but it’s more complicated than that. It was an island. A literal floating city in the middle of a massive, salty lake system that doesn't even exist anymore. Honestly, looking at a modern Google Map of the Zócalo and trying to imagine 200,000 people living on chinampas (artificial islands) is a trip.

The scale was massive. When Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier with Hernán Cortés, first saw it in 1519, he basically thought he was dreaming. He wrote about seeing "enchanted visions" from the book of Amadis. It wasn't just a village; it was a sophisticated urban grid that made 16th-century London look like a muddy backwater.

The Geography of a Vanished Lake

The first thing you have to understand about the location is Lake Texcoco. This wasn't some little pond. It was part of a five-lake system in the Valley of Mexico. Tenochtitlan sat on an island in the western part of that lake. If you’re looking at a historical reconstruction of Tenochtitlan on a map, you’ll notice it’s connected to the mainland by three main causeways: Tepeyac to the north, Iztapalapa to the south, and Tlacopan to the west.

These weren't just skinny bridges. They were massive stone highways wide enough for ten horses to ride abreast. They had removable sections too. If an enemy tried to invade, the Aztecs just pulled up the wooden planks and—boom—the city was a fortress.

The water management was honestly genius. Nezahualcoyotl, the "Poet King" of Texcoco, helped design a 10-mile-long dike to separate the fresh spring water near the city from the salty, brackish water of the main lake. Imagine that. They were terraforming at a level most modern engineers would find intimidating. They also had a double aqueduct system bringing fresh water from the springs at Chapultepec. If one pipe needed cleaning, they just switched to the other.

Why Your Modern Map Looks So Different

So, where did the water go?

Short answer: the Spanish hated it.

The Aztecs lived with the water. They used canoes for everything. But the Spanish wanted dry land. They wanted horses and carts and European-style streets. After the siege in 1521, they spent centuries draining the lake. They saw the water as a threat—a source of floods and "bad airs." By the 19th and 20th centuries, the Desagüe (the great drainage project) had basically turned a lush, aquatic paradise into a dusty basin.

📖 Related: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

When you look at Tenochtitlan on a map from the 1500s versus a map of CDMX today, the difference is jarring. The "lake" is now just pavement. This is also why Mexico City is sinking. The city is literally crushing the soft, clay-heavy lakebed it was built on. Parts of the city drop by twenty inches a year. You can see it in the old churches; they’re leaning at angles that would make the Tower of Pisa look stable.

The Sacred Precinct: The Heart of the Grid

If you want to find the exact center of the old city, go to the Templo Mayor. It's right next to the Metropolitan Cathedral. For centuries, people forgot exactly where the Great Temple was. Then, in 1978, some electrical workers digging a trench hit a massive stone disk depicting the goddess Coyolxauhqui.

- The Templo Mayor was the symbolic center of the universe (the axis mundi).

- It was dedicated to two gods: Huitzilopochtli (war/sun) and Tlaloc (rain).

- It was rebuilt seven times, each layer encased in the next like a Russian nesting doll.

Everything radiated out from this point. The four main neighborhoods—Cuepopan, Moyotlan, Zoquiapan, and Atzacoalco—corresponded to the cardinal directions. It was a perfectly ordered cosmos made of stone and mud.

Navigating the Lost Canals

Basically, the streets were canals. If you were a merchant coming from the south with a load of cacao or quetzal feathers, you didn't use a cart. You paddled. The city had thousands of canoes moving every single day.

The chinampas are the part people get wrong most often. They call them "floating gardens," but they didn't actually float. They were more like "anchored gardens." Farmers would weave fences of giant reeds, sink them into the lakebed, and fill them with mud and rotting vegetation. They planted willow trees (ahuejotes) at the corners because the roots would grow straight down and anchor the plot to the bottom.

This system was so productive it could feed the entire city. They could get up to seven harvests a year. Seven! In a world where most European farmers were lucky to get two, the Aztecs were living in post-scarcity abundance. You can still see a remnant of this at Xochimilco today. It’s the closest you’ll get to seeing what the outskirts of Tenochtitlan on a map actually felt like.

The Tlatelolco Connection

If you look at the northern part of the island on a map, you’ll see Tlatelolco. For a long time, it was a separate city. Eventually, the Tenochca (the people of Tenochtitlan) absorbed it. This was the commercial hub.

👉 See also: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

The market at Tlatelolco was insane. Cortés's guys estimated that 60,000 people gathered there every day. They had their own judges, their own "police," and everything was organized by product. Gold in one aisle, dogs for food in another, herbs over there. They even had a sophisticated currency system using cacao beans and standardized lengths of cotton cloth called quachtli.

The Map of Nuremberg (The First Look)

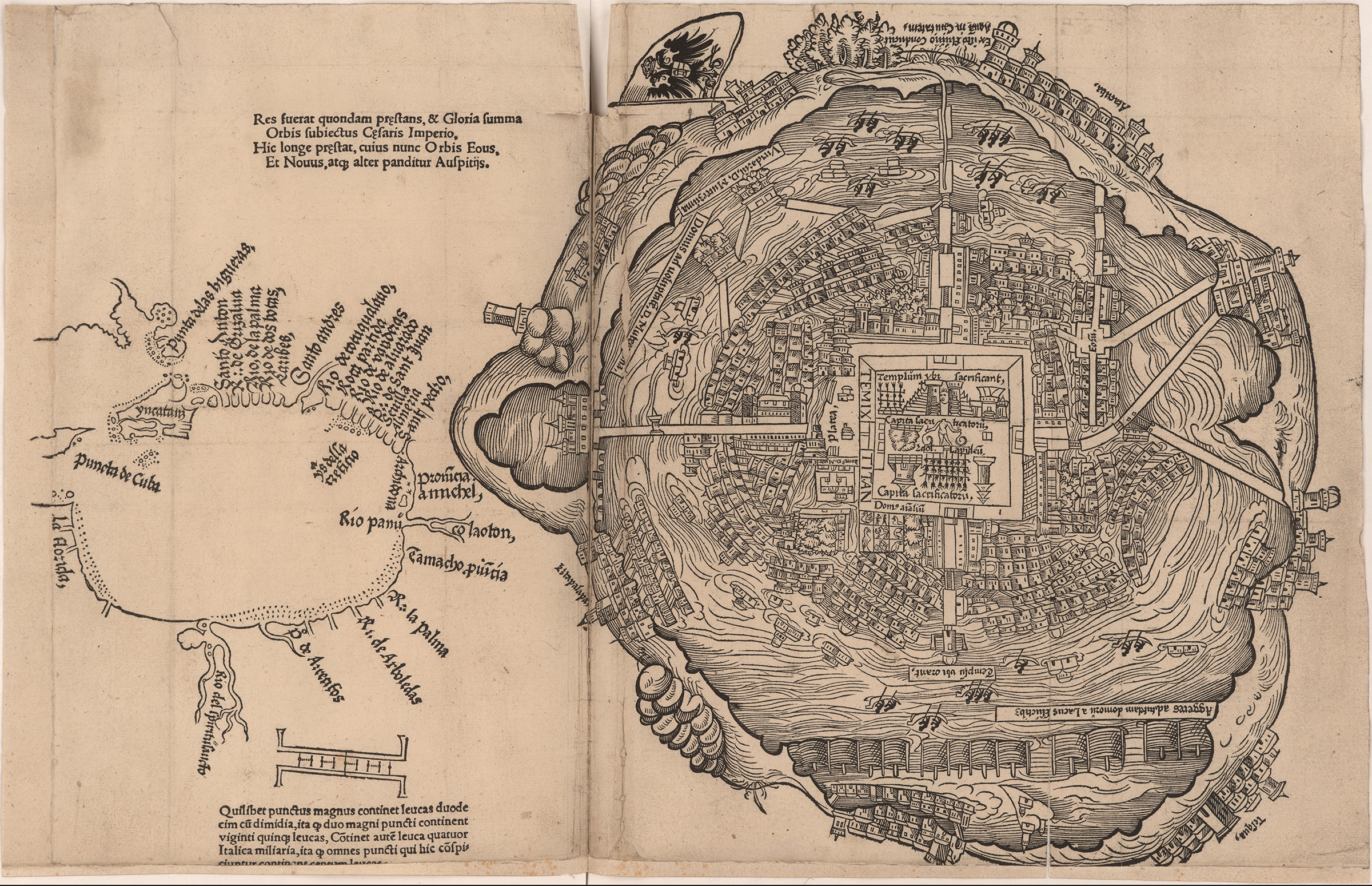

One of the most famous ways we know what the city looked like is the "Nuremberg Map," published in 1524 alongside Cortés’s letters to King Charles V. It’s a woodcut, and it’s beautiful.

It shows the city as a perfect circle with the sacred precinct in the middle. Is it perfectly accurate? Probably not. It was made by an artist in Germany who had never seen the place, based on sketches from soldiers. But it captured the vibe—the order, the canals, and the sheer impossibility of a stone city sitting on a lake 7,000 feet up in the mountains.

Tracing the Ruins Today

If you're on the ground in Mexico City and you want to "see" the map, you have to look for the ghosts.

- The Zócalo: This was the open plaza in front of Montezuma’s palace.

- Calle de Tacuba: This is one of the oldest streets in the Americas. It follows the exact path of the old Tlacopan causeway. When you walk down it, you’re walking the same route the Spanish used during the "Noche Triste" when they tried to flee the city and got decimated.

- Pino Suárez: Under the metro station here, there’s a small altar to Ehecatl (the wind god). It was part of a larger complex that just happened to be in the way of a subway line.

Mapping the Destruction

The siege of Tenochtitlan lasted about 80 days. It wasn't just a battle; it was urban's wrecking. Because the city was built on water, the Spanish couldn't use their cavalry effectively. So, they built brigantines—small ships—and fought a naval war in the middle of the mountains.

As they took the city, they tore down the buildings and used the rubble to fill in the canals. They literally paved over the Aztec world with its own bones. When you look at Tenochtitlan on a map today, you’re looking at a site of massive ecological and cultural transformation. The salt water of the lake became the dust of the city.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Explorer

Mapping this place in your mind is easier if you follow these steps:

✨ Don't miss: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

Visit the National Museum of Anthropology first. Don't just go to the ruins. Go to the museum in Chapultepec Park. They have a massive scale model of the city that makes the geography click. You’ll see how the mountains (the Sierra Nevada) hemmed in the lake.

Walk the "Triple Alliance" points.

To get a sense of the lake's scale, visit the sites of the other members of the alliance: Texcoco to the east and Tlacopan (Tacuba) to the west. Seeing the distance between them helps you realize how much water was actually drained.

Use the "Guía de Forasteros" overlays.

There are several digital projects, like the ones from UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), that allow you to overlay 1519 maps onto modern satellite imagery. Use these while standing in the Zócalo to see where the old canals ran right under your feet.

Check the water levels.

If you visit Xochimilco, take a trajinera (boat) but try to go to the "chinampa de la llorona" or the more remote areas. The central tourist zones are loud, but the quiet back-canals still feel like the 1400s.

Look at the stones.

Look at the walls of the Metropolitan Cathedral. You’ll see carved Aztec stones built into the foundations. The map didn't just disappear; it was recycled.

Understanding the layout of Tenochtitlan isn't just a history lesson. It’s a lesson in how humans interact with their environment. The Aztecs built a city that breathed with the lake. The Spanish built a city that fought it. We are still seeing the results of that conflict in the way Mexico City functions—or doesn't—today. The map is still there, hiding under the asphalt, waiting for a heavy rain to remind everyone that this was, and always will be, a lakebed.

***