Rome is a dot. Honestly, if you look at a standard atlas, that’s all you get—a tiny black circle nestled on the "boot" of Italy. But trying to find Rome on the map isn't just about GPS coordinates or spotting the Tiber River winding toward the Tyrrhenian Sea. It's about understanding how a single city managed to center itself in the middle of the known world for a thousand years.

You’ve probably seen the classic satellite views. You see the dense, terracotta-roofed sprawl. You see the green patches of the Villa Borghese. But maps are lying to you, or at least they’re oversimplifying things.

Most travelers pull up Google Maps, type in "Rome," and follow the blue dot. They miss the logic of the Seven Hills. They ignore why the city sits exactly 15 miles inland. Maps show you where Rome is, but they rarely show you why it is.

Where Exactly Is Rome on the Map?

Let’s get the technicalities out of the way before we get into the weird stuff. Rome sits at roughly 41.9 degrees North latitude and 12.4 degrees East longitude. If you’re looking at a map of Europe, it’s almost exactly halfway down the Italian peninsula on the western side.

It’s in the Lazio region.

People often think Rome is a coastal city because of its history as a Mediterranean superpower. It isn’t. Not quite. The heart of the city is tucked away from the salt air, protected by those famous hills—the Palatine, Aventine, Capitoline, and the rest. The Tiber River was the original highway. It connected the inland hills to the port at Ostia. Without that specific river placement on the map, Rome would have been just another hilltop village that got swallowed by its neighbors.

The terrain matters. If you look at a topographical map, you’ll notice the city sits in a volcanic area. The "Campagna Romana" is a low-lying plain surrounding the city. To the east, you’ve got the Apennine Mountains acting like a giant spine for Italy. To the west, the sea. Rome is the bottleneck. It’s the perfect place to control north-south traffic.

📖 Related: How to Actually Book the Hangover Suite Caesars Las Vegas Without Getting Fooled

The Seven Hills and the Grid (Or Lack Thereof)

Ancient Romans were obsessed with maps, but not like we are. They used things like the Forma Urbis Romae, a massive marble map of the city created under Emperor Septimius Severus. It was 60 feet wide. Imagine a marble wall showing every floor plan of every building in the city.

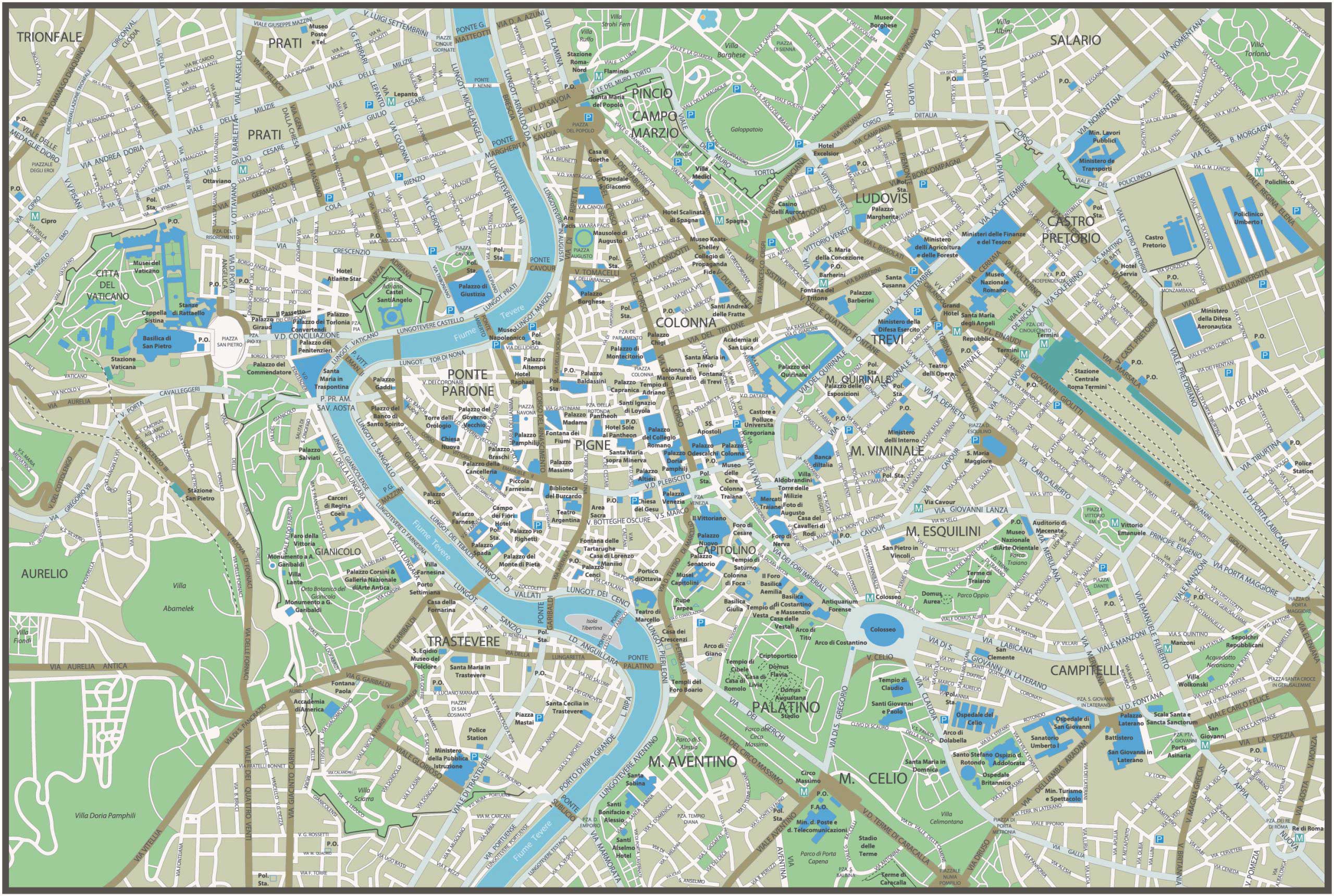

Today, if you try to navigate Rome using a standard grid mindset, you’ll lose your mind. The city wasn't planned; it erupted.

- The Centro Storico: This is the tangle of streets where the Pantheon sits. On a map, it looks like a bowl of spilled spaghetti.

- Trastevere: Literally "across the Tiber." It’s the bohemian lung of the city, tucked into the curve of the river.

- The Vatican: A country inside a city. It’s the smallest sovereign state in the world, appearing as a tiny walled enclave on the western edge of the center.

The weird thing about looking at Rome on the map today is seeing the ring road, the Grande Raccordo Anulare (GRA). It’s a massive circular highway that traps the city in a 42-mile loop. Everything inside the GRA is "Rome," but the soul of the city is that tiny, dense core that hasn't changed its basic footprint since the days of Augustus.

Why the Tiber Looks Different Now

Look at a map from the 1700s. The Tiber River looks wild. It used to flood constantly. In the late 19th century, they built the lungotevere—the massive stone walls that line the river today. On a modern map, the river looks like a neat, controlled ribbon. In reality, it’s a sunken corridor. You can walk for miles along the water and barely see the city above you. This changed the visual "map" of Rome forever, turning the river from a chaotic neighbor into a quiet, subterranean park.

Misconceptions About Rome’s Location

One of the biggest mistakes people make when looking at Rome on a map is thinking it’s "down south."

It’s central.

👉 See also: How Far Is Tennessee To California: What Most Travelers Get Wrong

If you take a train from Rome, you can be in Florence (the north) in 90 minutes or Naples (the south) in 70 minutes. Rome is the pivot point. This is why it’s the capital. It wasn't the first choice for the capital of a unified Italy—Turin and Florence held the title first—but Rome’s position on the map was too symbolic to ignore. It’s the only city that could hold the country together because it belongs to neither the industrial north nor the agrarian south.

Another weird fact? Rome is on the same latitude as Chicago. That sounds wrong, doesn't it? You think of Rome as sunny, Mediterranean, and palm-tree-adjacent. Yet, geographically, it’s aligned with the Windy City. The only reason Romans aren't shoveling snow every January is the Mediterranean Sea, which acts as a giant heat sink, keeping the climate temperate while the US Midwest freezes.

How to Actually Read a Roman Map

If you’re planning to visit or just studying the layout, stop looking at the whole city. Focus on the rioni.

Rome is divided into 22 historic districts called rioni. Each has its own personality, and more importantly, its own map logic. Rione I is Monti. It’s the oldest part of the city, where the Suburra (the ancient slums) used to be. On a map, it’s right next to the Colosseum.

Then you have Prati. It’s near the Vatican. But Prati looks different on the map. It has wide, straight streets and a grid system. Why? Because it was built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to house the new bureaucracy of the Italian Kingdom. They intentionally designed it so you couldn't see the St. Peter’s Basilica dome from the main streets—a bit of a "middle finger" from the secular government to the Pope.

Navigating the "Hidden" Maps

There are actually three Romes on the map at any given time:

✨ Don't miss: How far is New Hampshire from Boston? The real answer depends on where you're actually going

- The Ancient Layer: The Forum, the Palatine Hill, and the ruins buried 20 feet below the current street level.

- The Catholic Layer: The 900+ churches that act as navigational landmarks.

- The Modern Layer: The graffiti-covered metro lines (there are only three, because every time they dig, they hit an ancient palace).

When you look at the map of the Metro (Line A, B, and C), you’ll notice a giant empty space in the middle. That’s the historic center. You can’t put a subway there. The map is literally dictated by the ghosts of the past. If you want to get across the "hook" of the Tiber, you’re walking or taking a bus.

The Practical Logistics of Finding Your Way

If you are trying to find your way around, don't trust the street names. One street can change names three times in four blocks.

Instead, look for the "piazze." Rome is a series of nodes. Piazza del Popolo, Piazza Navona, Piazza Venezia. If you can find these on the map, you can navigate the city. Think of the piazze as the anchors and the streets as the chaotic ropes connecting them.

And remember the fountains. Rome has over 2,000 fountains. The nasoni (big noses) are the small cast-iron fountains with free-flowing cold water. They are everywhere. There are even apps now that map nothing but these water sources. In a city that hits 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer, that’s the most important map you’ll ever own.

What You Should Do Next

Finding Rome on the map is the easy part. Understanding it requires a bit of footwork and a shift in perspective.

- Check the Elevation: Don't just look at a flat map. Use a 3D view or a topographical map to see how the hills dictate the flow of the city. Walking from the Forum to the Quirinale is a steep climb you won't see on a standard paper map.

- Study the Rioni: Before you go, pick three rioni (like Trastevere, Monti, and Testaccio) and look at their individual layouts. You’ll see the history of the city’s expansion written in the street widths.

- Look at the Gates: Find the "Porta" names on the map—Porta Pia, Porta San Giovanni. These were the gates in the Aurelian Walls. They tell you where the "real" city ended for nearly 1,500 years.

- Trace the Aqua Virgine: Research the ancient aqueducts. One of them, the Aqua Virgine, still functions and feeds the Trevi Fountain. Mapping the path of the water is a fascinating way to see how the ancient and modern cities overlap.

Rome isn't just a location; it's a stack of maps layered on top of each other. Whether you're looking at a satellite image or a hand-drawn map of the bus routes, you're looking at a puzzle that’s been under construction for 2,700 years. Stop looking for a destination and start looking for the layers.