Look at a map. Really look at it. Most people think they know exactly what they're seeing when they search for Manhattan on a map, but the reality is way more cramped and complicated than the glossy postcards suggest. It’s a skinny sliver of rock. Roughly 13.4 miles long and barely 2.3 miles wide at its fattest point.

Honestly, it’s tiny.

But that tiny footprint holds the weight of the world's economy. When you pull up a digital map of New York City, your eyes are naturally drawn to that central vertical rectangle, the one flanked by the Hudson River on the west and the East River on the... well, east. It’s easy to get turned around because Manhattan doesn't actually sit perfectly north-to-south. The whole island is tilted about 29 degrees east of true north. This is why "uptown" isn't actually north, and "crosstown" is a diagonal nightmare for tourists who trust their compass apps too much.

The First Thing You Notice About Manhattan on a Map

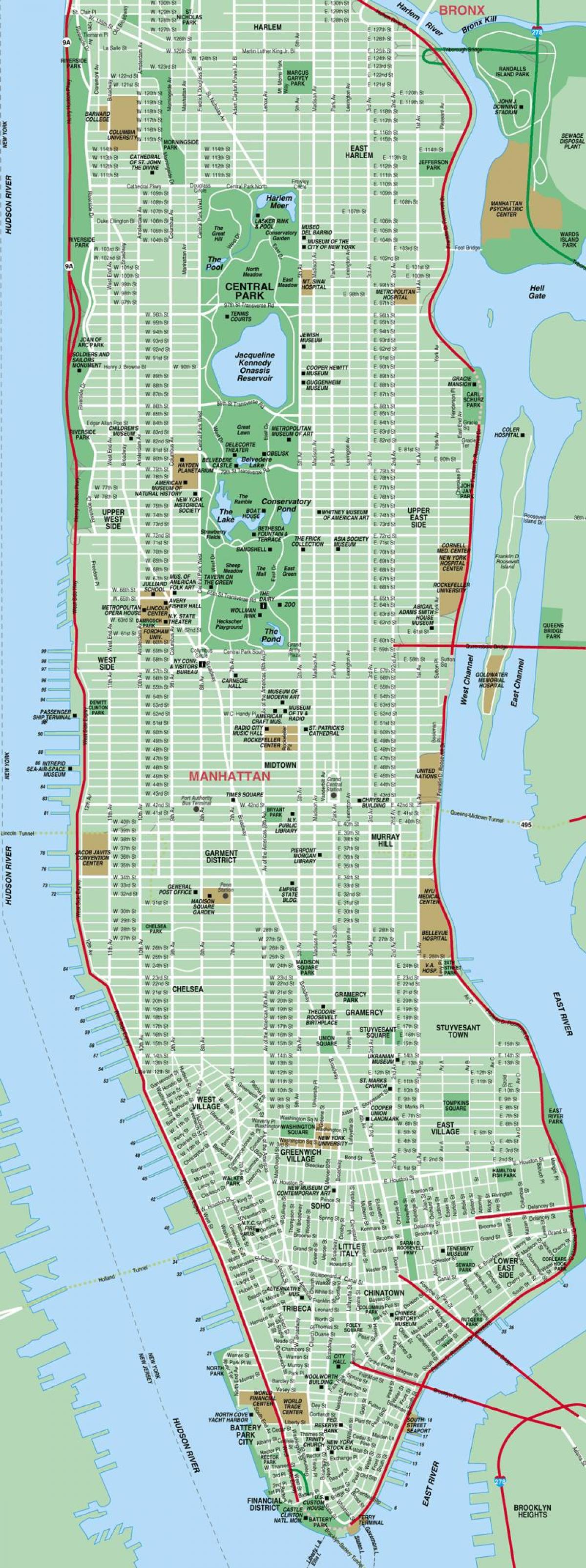

The grid. It’s the defining characteristic. If you’re looking at a map of the island, you’ll see the rigid, mathematical precision of the Commissioners' Plan of 1811. Before that, Manhattan was a mess of cow paths and swampy trails, which you can still see if you look at the bottom of the map—Lower Manhattan.

Down there, the streets are chaotic. Wall Street, Pearl Street, and Maiden Lane twist and turn like they were laid out by someone who had one too many ales at a colonial tavern. This is the original Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam. But move your eyes up past Houston Street (pronounced HOW-stun, never like the city in Texas), and the map suddenly snaps into a rigid, predictable cage.

Why the change? Efficiency. The city planners wanted to squeeze every dime out of the real estate. They didn't care about views or parks back then. In fact, if you look at the original 1811 map, Central Park isn't even there. It was a massive oversight that had to be corrected decades later when the city realized people actually need to breathe. Now, that green rectangle is the most recognizable landmark when you spot Manhattan on a map from a satellite view. It's the "lungs" of the city, sitting right there between 59th Street and 110th Street.

The Rivers Are Lying to You

Here’s a fun fact that most people get wrong: The East River isn't actually a river. If you’re tracing the border of Manhattan on a map, you’re looking at a tidal strait. It connects the Upper New York Bay to the Long Island Sound. It’s salt water. It flows both ways depending on the tide.

The Hudson River, on the western side, is a real river, but even it behaves like an estuary all the way up to Troy. This geography matters because it’s why Manhattan became a powerhouse. Deep water on both sides meant ships could dock almost anywhere. If you zoom in on a high-resolution map of the West Side or the Seaport area, you can still see the "finger piers" jutting out like teeth. Most are gone or turned into parks like Little Island or Pier 57, but the map still remembers the industrial past.

Identifying the Neighborhoods Without Labels

You don't need text labels to understand what you're looking at if you know the visual cues.

🔗 Read more: Getting From the Eiffel Tower to Louvre: What the Guidebooks Usually Miss

The "Bow" of the island is the Battery. That's the very southern tip. From there, the island widens. Look for the massive cluster of gray and beige blocks around Mid-town—that’s where the bedrock is strongest. Geologists like Charles Merguerian have pointed out for years that the skyscrapers are where they are because of the Manhattan Schist. It’s a tough metamorphic rock that can support the weight of the Empire State Building.

If you see a dip in the skyline on a 3D map between Midtown and Financial District, that’s because the bedrock dives deep underground. The buildings there are shorter because it was too expensive to dig down to the rock. The map tells the story of the ground beneath it.

Then there’s the "Marble Hill" quirk. If you look at the very top of Manhattan on a map, you might see a tiny piece of land that looks like it belongs to the Bronx. It’s called Marble Hill. Geographically, it’s attached to the mainland. Legally? It’s Manhattan. In 1895, the city dug the Harlem River Ship Canal, which physically cut Marble Hill off from the rest of the island. Eventually, they filled in the old creek bed, physically attaching it to the Bronx. But the residents there still vote in Manhattan and have Manhattan zip codes. It’s a cartographic glitch that drives GPS systems crazy.

Scale is Everything

People underestimate the walkability. Or they overestimate it.

You see that stretch from the bottom of the map to the top? If you tried to walk it, you’re looking at about 4 to 5 hours of steady moving, assuming you don't stop for a bagel. The "blocks" in Manhattan are asymmetrical. Walking 20 blocks north-south (Avenues) is roughly one mile. Walking just 3 blocks east-west (Streets) can be the same distance. This is why "Crosstown" is a dirty word in New York. The map makes it look like a quick skip, but the reality is a slog through traffic and long stretches of concrete.

The Secret Islands of the Borough

When people search for Manhattan on a map, they usually just look at the big island. But Manhattan actually includes several smaller islands that are often ignored.

- Roosevelt Island: That long, skinny sliver in the East River. It’s got its own tram.

- Governors Island: The ice cream cone-shaped park at the bottom. It used to be a military base.

- Randall’s and Wards Islands: Connected to the Upper East Side and Harlem by bridges, mostly used for parks and facilities.

- Ellis Island and Liberty Island: This is where it gets spicy. While the Statue of Liberty is in New York waters and is technically part of Manhattan’s territory (mostly), Ellis Island is actually split between New York and New Jersey. A 1998 Supreme Court case decided that the filled-in portions of Ellis Island belong to New Jersey. So, if you’re looking at a precise political map, you’ll see a jagged line cutting right through the buildings.

The Impact of "Manhattanhenge" on the Map

Twice a year, the sun aligns perfectly with the east-west streets of the Manhattan grid. This happens because of that 29-degree tilt I mentioned earlier. If the island were perfectly aligned with the poles, this wouldn't happen on the dates it does. It’s a moment where the physical layout of the city—that rigid map—interacts with the cosmos. It turns the streets into "urban canyons."

🔗 Read more: Why Jones Mill Mountain Bike Trail is Middle Tennessee's Best Kept Secret

Why Digital Maps are Changing the Island

In the old days, you’d carry a folded Hagstrom map. It was huge. It was tactile. Today, Google Maps and Apple Maps have changed how we perceive Manhattan on a map. We no longer see the whole island; we see a blue dot in a 500-foot radius.

This has actually made people worse at navigating. We lose the sense of where the water is. In Manhattan, the water is your north star. If you know where the Hudson is, you can’t get lost. Digital maps prioritize "Points of Interest," which clutters the screen with coffee shop icons and obscures the actual geography. If you want to understand the island, turn off the "labels" layer on your map and just look at the bones of the streets.

Getting the Most Out of Your Map Search

If you’re planning a trip or just trying to understand the layout, don't just look for a flat image.

- Use the 3D toggle. This shows the "Manhattan Valley" in Morningside Heights and the massive cliffs of Washington Heights (which is the highest natural point on the island at 265 feet).

- Check the subway overlay. Manhattan’s geography is dictated by the trains. The "West Side" (1/2/3 and A/C/E) and the "East Side" (4/5/6 and Q) are distinct worlds because the geography of the island makes it hard to move between them.

- Look at the bathymetry. If you can find a map that shows the depth of the water surrounding Manhattan, you’ll see why the ports were built where they were. The "Narrows" at the bottom of the map acts like a funnel, protecting the harbor from the worst of the Atlantic's moods.

Manhattan isn't just a place; it's a masterpiece of engineering laid over a rugged, rocky spine. Whether you're looking at a vintage 19th-century lithograph or a 2026 satellite feed, the island's shape remains iconic. It’s a testament to how humans can take a small, swampy piece of land and turn it into the center of the universe.

👉 See also: South Padre Island on map: Why Most People Get Lost Before They Even Arrive

Actionable Insights for Your Next Map Search

- Orient yourself by the grid: Remember that 5th Avenue divides the East and West sides. Anything with a "West" address is toward the Hudson; "East" is toward the East River.

- Don't ignore the "Heights": If the map shows a lot of green and winding roads at the very top, you’re looking at Inwood and Washington Heights. It’s the only part of the island that still feels like the original, hilly terrain.

- Identify the "Super-talls": On modern 3D maps, look for the "Billionaire's Row" cluster just south of Central Park. These needles are the newest addition to the cartographic profile of the island.

- Watch the shadows: If you're using a satellite map, the length of the shadows can tell you the time of day the photo was taken, which is a fun way to see how the "canyon effect" works in real life.

Stop looking at it as just a destination. Look at it as a puzzle. Every street name and every pier has a reason for being there. Next time you pull up Manhattan on a map, look past the tourist traps and see the rock, the grid, and the water that made it all possible.