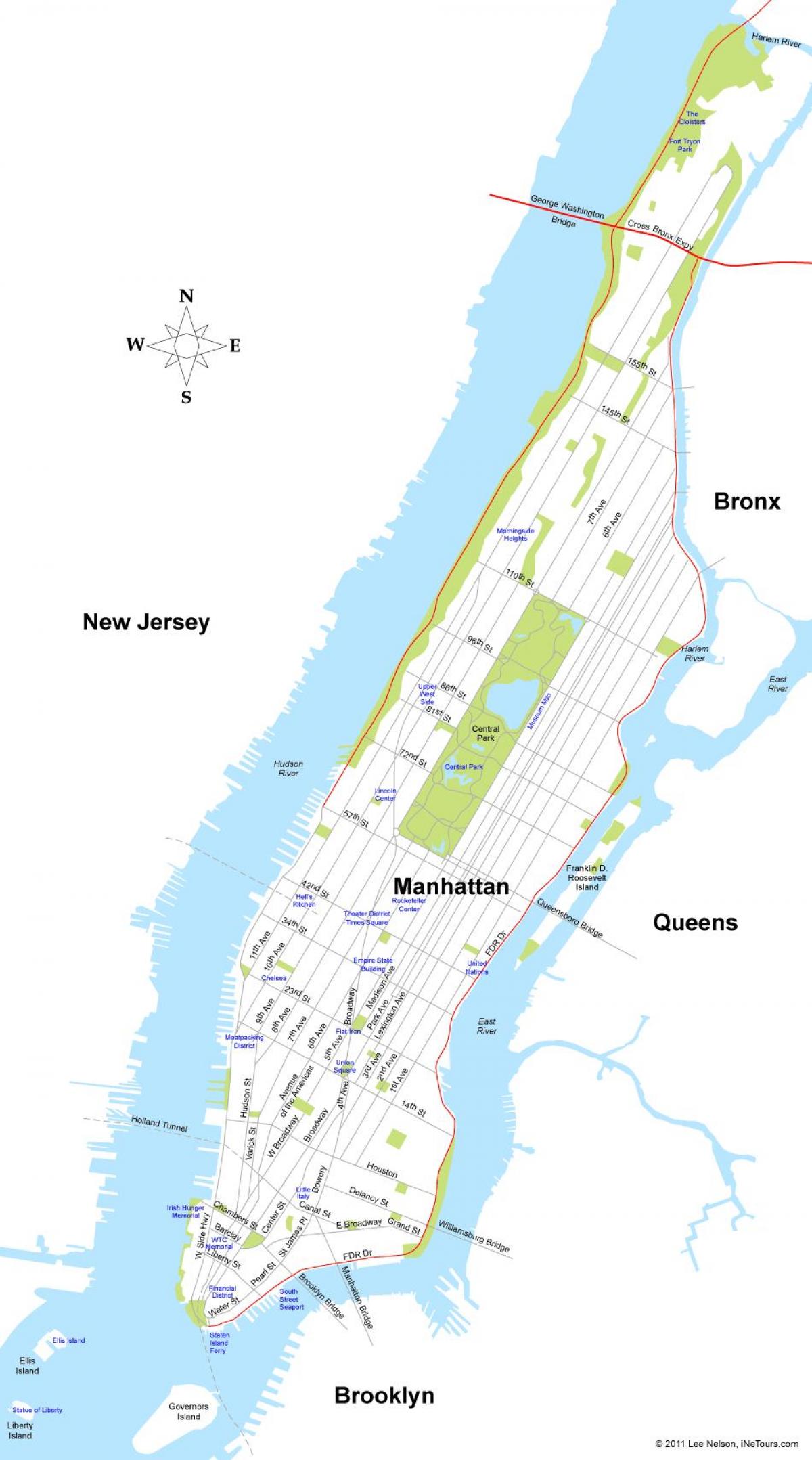

Look at it. Just look at it. If you open a standard map of New York City, your eyes go straight to that skinny, vertical sliver right in the middle. That’s Manhattan. It’s basically a 13-mile-long rock floating between the Hudson and East Rivers. But honestly, finding Manhattan island on map is the easy part; understanding why it looks like a giant Tetris grid is where things get interesting. Most people think the city was always this organized. It wasn’t. Before the planners got their hands on it, the island was a mess of hills, swamps, and jagged trails that made absolutely no sense to anyone trying to build a global powerhouse.

The Grid That Tamed the Island

Back in 1811, some guys—specifically the Commissioners—decided they’d had enough of the chaotic, winding streets of Lower Manhattan. They laid down a plan. It was bold. It was arguably boring. But it was efficient. They draped a rectangular grid over the entire island, stretching from what we now call Houston Street all the way up to 155th. If you’re looking at Manhattan island on map today, you see those straight lines and right angles. That’s the 1811 Commissioners' Plan in action.

They didn't care about the topography. They leveled hills. They filled in streams. They wanted "right-angled houses" because they were cheaper to build and easier to sell. It’s why, if you’re standing on 5th Avenue, you can see forever. Except for Broadway. Broadway is the rebel. It follows an old Wickquasgeck trail used by Native Americans, slicing diagonally across the grid and creating those weird, triangular spaces like Times Square and Union Square.

It’s Not Actually a Straight Line

Here’s a fun fact that drives cartographers crazy: Manhattan isn't oriented North-South. Not really. If you look at a compass on a Manhattan island on map view, you’ll notice the island is tilted about 29 degrees to the east. When a New Yorker tells you to go "Uptown," they aren't telling you to go North. They’re telling you to go Northeast. This tilt is the secret behind "Manhattanhenge." Twice a year, the sunset aligns perfectly with the east-west streets. It’s a massive tourist trap now, but it’s a direct result of that specific 29-degree offset from true geographic north.

🔗 Read more: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

The island itself is tiny. We’re talking roughly 22.7 square miles. You can walk the whole length of it in a day if you have good shoes and enough caffeine. But despite its size, it holds the weight of the world—literally and figuratively. The bedrock is mostly Manhattan Schist. This stuff is incredibly tough. It’s the reason the skyline looks the way it does. In Midtown and Lower Manhattan, the schist is close to the surface, allowing developers to anchor massive skyscrapers deep into the earth. In between, like around Chelsea or Greenwich Village, the bedrock dips way down. That’s why the buildings there are shorter. The map of the skyline is just a map of the geology underneath.

The "Missing" East Side and Hidden Islands

People often forget that Manhattan isn’t just the big island. When you’re scanning a Manhattan island on map layout, you have to look for the little guys. You’ve got Roosevelt Island sitting in the East River like a skinny cigar. You’ve got U Thant Island, which is barely a patch of dirt created from subway tunnel spoils. And then there’s Marble Hill.

Marble Hill is a geographical identity crisis. Originally, it was part of the mainland of Manhattan. But then, in 1895, the city dug the Harlem River Ship Canal to make navigation easier. Suddenly, Marble Hill was an island. Then, they filled in the old creek bed that used to separate it from the Bronx. Now, Marble Hill is physically attached to the Bronx, but it’s still legally part of Manhattan. If you’re a mailman there, you’re probably annoyed. If you’re a map geek, it’s hilarious.

💡 You might also like: Where to Actually See a Space Shuttle: Your Air and Space Museum Reality Check

Why the Waterfront Looks "Fake"

Because it kinda is. If you compare a Manhattan island on map from 1609 to one from 2026, the current version is much "fatter." New Yorkers have been dumping dirt and trash into the rivers for centuries to create more real estate. Battery Park City? That’s entirely man-made. It was built using the dirt excavated from the original World Trade Center site.

The shoreline is a jagged mess of piers and bulkheads. It’s a constant battle against the water. The East River isn't even a river; it’s a tidal strait. It changes direction based on the tide, which makes it incredibly dangerous for swimmers but great for moving silt around. When you look at the map, notice how the West Side (the Hudson) has longer piers. The water is deeper there, which is why the big cruise ships and old ocean liners always docked on the West Side instead of the East.

Navigating the Map Like a Local

If you want to master the island, stop looking at the pretty colors and look at the numbers.

The street numbering system is a masterpiece of logic. 5th Avenue divides the island into East and West. As you move away from 5th, house numbers go up. 10 West 18th Street is just a few doors down from 5th. 300 West 18th Street is way over by the river. It’s predictable. It’s cold. It’s perfect.

📖 Related: Hotel Gigi San Diego: Why This New Gaslamp Spot Is Actually Different

Except for the Village.

Greenwich Village is where the grid goes to die. Because that neighborhood was already settled before the 1811 plan, the residents refused to let the city steamroll their streets. That’s why West 4th Street somehow manages to intersect with West 12th Street. It’s a topographical nightmare that humbles even the best GPS apps. If you find yourself there, just put the phone away and look for a landmark.

Practical Steps for Your Next Visit

Don't just stare at a digital screen. To really understand the scale of Manhattan island on map layouts, you need to see it from above and below.

- Get to a High Point: Go to the Edge at Hudson Yards or the One World Observatory. Look at the grid. See how the "valleys" of shorter buildings correspond to where the bedrock sinks.

- Walk the Perimeter: Use the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway. It’s a continuous path that lets you circumnavigate almost the entire island. You’ll see the bridges—21 of them connect Manhattan to the rest of the world—and realize just how isolated this rock actually is.

- Study the Subway Map: The MTA map is a "schematic," meaning it lies to you about distances to make the lines look pretty. Compare it to a geographic map to see how cramped the lines actually are in Lower Manhattan.

- Visit the High Line: It’s an old elevated rail line turned park. It gives you a "middle-ground" perspective of the street grid that you can't get from the sidewalk or a skyscraper.

Manhattan is a living organism built on a rigid skeleton. The map tells you where the streets are, but the geology and the history tell you why they stay there. Whether you're tracking the diagonal defiance of Broadway or the artificial expansion of the shoreline, the island remains a feat of stubborn engineering.