Chemistry is weird. You’ve got these salts that supposedly don't dissolve in water, but honestly, everything dissolves a little bit. That tiny, microscopic amount that actually manages to break apart into ions is what we call molar solubility. If you can measure that, you can figure out the Solubility Product Constant, or $K_{sp}$.

It sounds easy. It’s not. Most people trip up on the math or forget that coefficients are basically the "boss" of the entire equation. If you want to master finding Ksp from molar solubility, you have to stop thinking about formulas for a second and look at how the molecules actually behave when they hit the water.

What is Molar Solubility anyway?

Before we dive into the $K_{sp}$ math, let's be real about what molar solubility actually represents. It’s the number of moles of a solute that can dissolve in a liter of solution before that solution becomes "saturated." Saturated just means the water has had enough; it literally cannot hold any more of that substance. If you add more, it just sits at the bottom of the beaker looking lonely.

Molar solubility is usually represented by the letter $s$. Think of $s$ as the "amount that disappeared" into the liquid. It's the starting point for everything. If you don't have $s$, you can't get to $K_{sp}$. Often, a textbook will give you solubility in grams per liter (g/L). That’s a trap. You have to convert that to moles per liter (mol/L) using the molar mass before you even think about the equilibrium constant.

The Equilibrium Constant and the Ice Table

$K_{sp}$ is just a specific type of equilibrium constant. It describes the balance between the solid salt and its dissolved ions. For a generic salt like $AB$, the equation looks like this:

$$AB(s) \rightleftharpoons A^+(aq) + B^-(aq)$$

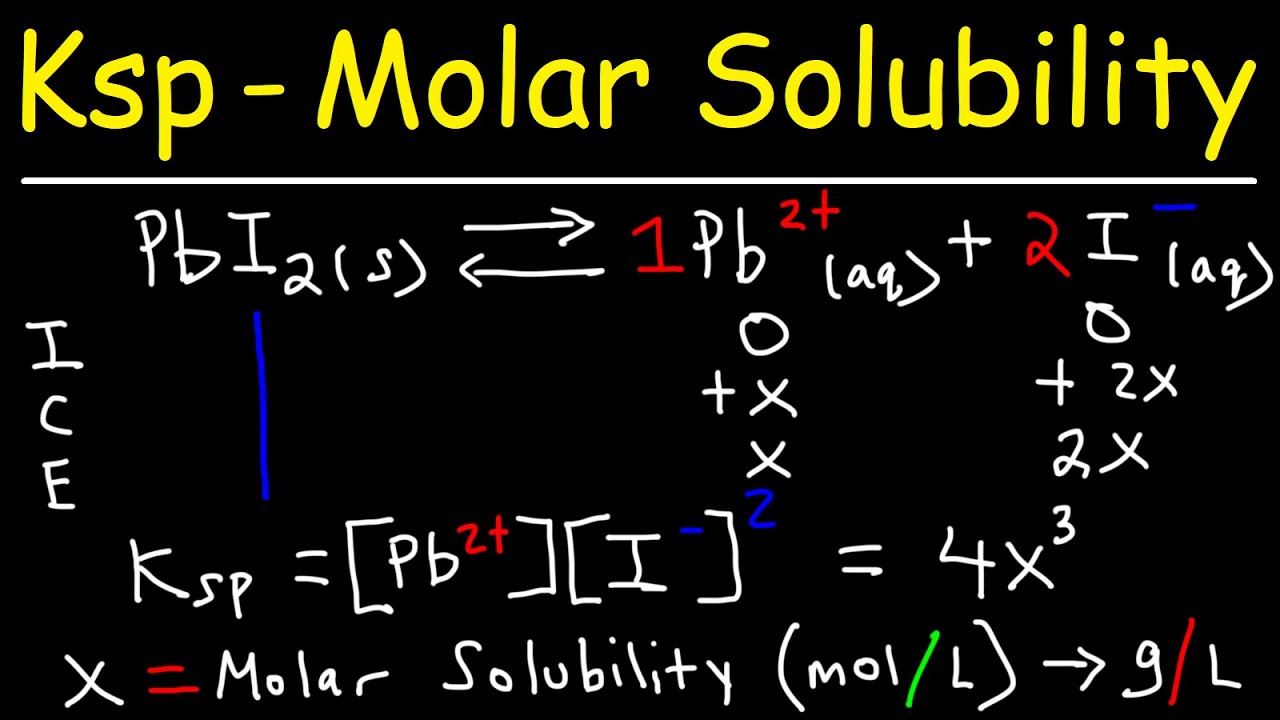

But chemistry is rarely that simple. Salts come in different "flavors" or ratios. You might have $PbCl_2$ or $Ag_2CO_3$. These ratios change the math entirely. This is where the ICE table (Initial, Change, Equilibrium) usually comes in, though most experts eventually just do the mental math.

The Step-by-Step of finding Ksp from molar solubility

Let’s look at a real example. Silver chromate ($Ag_2CrO_4$) is a classic. It’s a beautiful red-brown solid. If someone tells you the molar solubility of silver chromate is $1.3 \times 10^{-4}$ M, how do you find the $K_{sp}$?

Step 1: Write the balanced dissociation equation.

This is the most important part. If you mess this up, the rest is garbage.

$$Ag_2CrO_4(s) \rightleftharpoons 2Ag^+(aq) + CrO_4^{2-}(aq)$$

Notice that $2$ in front of the Silver? It’s going to haunt us. It means for every 1 mole of silver chromate that dissolves, you get 2 moles of Silver ions.

Step 2: Express the concentrations in terms of $s$.

Since the molar solubility is $s$, the concentration of $CrO_4^{2-}$ is just $s$. But the concentration of $Ag^+$ is $2s$.

Step 3: Plug it into the Ksp expression.

The general rule for $K_{sp}$ is that you multiply the products and raise them to the power of their coefficients.

$$K_{sp} = [Ag^+]^2 [CrO_4^{2-}]$$

Now, substitute the $s$ values:

$$K_{sp} = (2s)^2 \times (s)$$

$$K_{sp} = 4s^2 \times s$$

$$K_{sp} = 4s^3$$

Step 4: Solve with the actual numbers.

Now you just plug in that $1.3 \times 10^{-4}$ for $s$.

$$K_{sp} = 4 \times (1.3 \times 10^{-4})^3$$

Doing the math (carefully!), you get roughly $8.8 \times 10^{-12}$.

Why the "Square the Double" Rule trips everyone up

Look at that $4s^3$ again. You had to double the $s$ because there were two silver ions, and then you had to square that whole term because of the coefficient in the $K_{sp}$ expression. It feels like double-dipping. It feels wrong. Students always ask, "Why am I using the 2 twice?"

The answer is simple: The first 2 accounts for the amount of ions produced. The second 2 (the exponent) accounts for the law of mass action which governs the rate of the reaction. You have to do both. No shortcuts.

Common Ratios and their Ksp Formulas

If you do this enough, you start to see patterns. You don't always need a full ICE table if you recognize the stoichiometry of the salt.

- 1:1 Salts (like AgCl or MgSO4): $K_{sp} = s^2$

- 1:2 or 2:1 Salts (like MgF2 or Li2O): $K_{sp} = 4s^3$

- 1:3 or 3:1 Salts (like Al(OH)3): $K_{sp} = 27s^4$

- 2:3 or 3:2 Salts (like Ca3(PO4)2): $K_{sp} = 108s^5$

Wait, $108s^5$? Yeah. For Calcium Phosphate, the math gets wild. You have $(3s)^3 \times (2s)^2$, which is $27s^3 \times 4s^2$. Multiply those together and you get 108. It’s basically just algebra at that point, but one small slip with a calculator and you’re miles off the correct answer.

Real-World Factors: It's never just "Pure Water"

In a lab, things get messy. We talk about finding Ksp from molar solubility as if we’re always working with pure, distilled water at exactly $25^\circ C$. Life isn't that clean.

The Common Ion Effect

If you try to dissolve AgCl in a solution that already has NaCl in it, the AgCl isn't going to dissolve nearly as much. Le Chatelier’s Principle kicks in and pushes the reaction back toward the solid side. The $K_{sp}$ value itself stays the same (usually), but the molar solubility ($s$) drops significantly.

👉 See also: How Do You Reset Your Instagram Algorithm Without Losing Your Account?

Temperature is everything

Solubility is heat-dependent. Most salts dissolve better in hot water, but not all. If your textbook doesn't specify $25^\circ C$, the $K_{sp}$ values you find in the back of the book might not match your results. This is why solubility curves are such a huge deal in industrial chemistry and pharmacology.

The pH Factor

If you're dealing with a salt that has a basic ion—like Magnesium Hydroxide $Mg(OH)_2$—the acidity of the water matters. In an acidic environment, the $OH^-$ ions get "eaten" by the $H^+$ ions, which forces more of the solid to dissolve. This is literally how acid rain destroys limestone statues.

Why this actually matters in the real world

This isn't just "busy work" for chemistry students. Understanding how to calculate these values is vital in fields like:

- Medicine: If a drug is too soluble, it might hit your bloodstream too fast. If it’s not soluble enough, your body just passes it without absorbing it. Pharmacists use $K_{sp}$ to predict how medications behave in the body.

- Environmental Engineering: When treating wastewater, engineers add chemicals to make toxic heavy metals "precipitate" out as solids. To do that, they need to know exactly how much to add to exceed the $K_{sp}$.

- Geology: The formation of stalactites and stalagmites in caves is basically one giant, slow-motion $K_{sp}$ experiment involving calcium carbonate and carbon dioxide.

Troubleshooting your calculations

If your answers are coming out weird, check these three things. Seriously.

First, check your units. Did you use grams instead of moles?

Second, check your exponents. Did you square the 2 in $(2s)^2$ to get $4s^2$, or did you leave it as $2s^2$? (Everyone forgets to square the number!).

Third, check the temperature. If you're looking up a reference value, make sure it's for the right temp.

Moving Forward with Solubility Math

Once you’ve got the hang of finding $K_{sp}$ from $s$, the next logical step is going in reverse. Can you find the molar solubility if you’re only given the $K_{sp}$? It’s the same math, just backwards—you’ll be doing a lot of cube roots and fourth roots.

To really nail this, grab a sheet of paper and practice the $108s^5$ calculation for Calcium Phosphate. If you can do that one without hitting a snag, you’ve basically mastered the concept. After that, look into the "Ion Product" ($Q_{sp}$). Comparing $Q$ to $K$ is how chemists predict whether a precipitate will form when you mix two different clear liquids together. It’s like being a weather forecaster, but for chemical "storms" in a test tube.

Start by verifying the stoichiometry of your salt. Write out the dissociation. Identify $s$. Everything else is just a calculator away.

---