The ocean is a massive, salt-water graveyard that doesn't like giving up its secrets. For decades, the most famous shipwreck of World War II—John F. Kennedy’s torpedo boat—was basically a ghost. People knew where it happened, roughly. They knew about the collision with the Japanese destroyer Amagiri. But seeing it? That was a different story entirely. When the first PT 109 wreck pictures finally surfaced in 2002, they didn't look like a boat. They looked like a pile of twisted metal and shadow, resting 1,200 feet down in the Blackett Strait.

It’s a haunting sight.

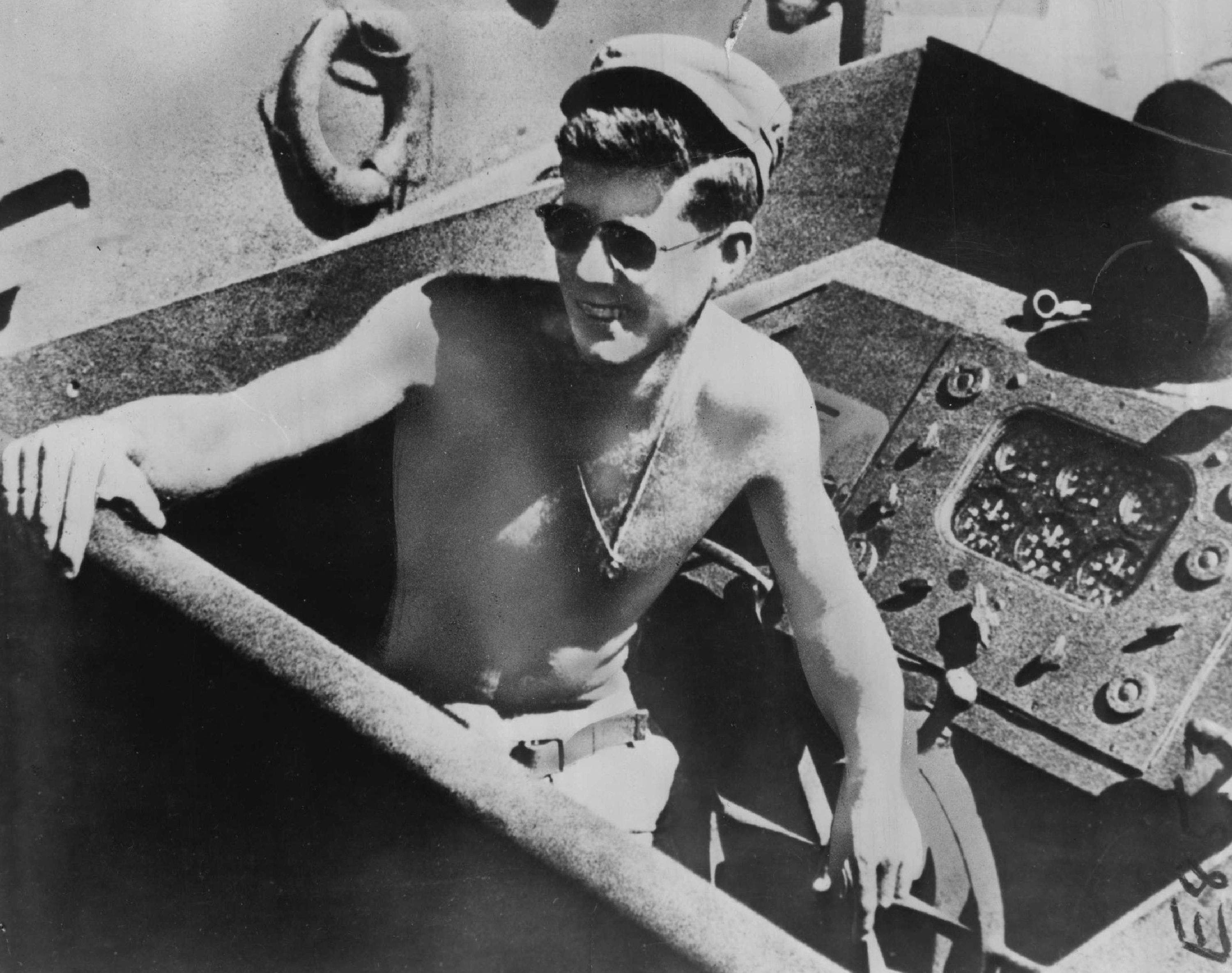

You've probably seen the grainy, black-and-white photos of a young, shirtless JFK on the deck of his boat. He looks invincible. But the images captured by Robert Ballard’s team tell a much grittier, more violent story of survival. There is no intact hull. There are no flags waving. Instead, the cameras captured the stark reality of a boat that was literally sliced in half by thousands of tons of steel moving at high speed.

Why the Hunt for PT 109 Took Fifty Years

Finding a wooden boat in the middle of the Pacific is a nightmare. Most PT boats were made of mahogany. In the warm, shipworm-infested waters of the Solomon Islands, wood usually lasts about as long as a New Year's resolution. It rots. It gets eaten. It disappears.

Robert Ballard, the same guy who found the Titanic and the Bismarck, knew this. He wasn't looking for a wooden hull. He was looking for the heavy stuff. He was hunting for the Packard engines. Those three massive engines, along with the torpedo tubes and the anti-aircraft guns, are the only things that could survive sixty years on the seafloor.

The search wasn't just a random hobby. It was a high-stakes archaeological mission supported by the National Geographic Society and the US Navy. They used side-scan sonar to map the floor of the Blackett Strait. The terrain is brutal. It's full of volcanic ridges and deep silt. For days, they found nothing but rocks. Then, a "target" appeared on the screen. It was small. It was isolated. It was exactly where the current would have pushed the wreckage on that dark night in August 1943.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

The First PT 109 Wreck Pictures: What Did We Actually See?

When the Remote Operated Vehicle (ROV) finally reached the site, the images it sent back were surreal. Honestly, if you didn't know what you were looking at, you might have missed it.

The most striking feature in the PT 109 wreck pictures is a Mark VIII torpedo tube. It’s sitting there, cocked at an angle, still holding a torpedo that was never fired. It’s a chilling reminder of how fast the disaster happened. Kennedy and his crew had no time to react. The Amagiri appeared out of the darkness, and within seconds, the 109 was a wreck.

The Anatomy of the Debris Field

- The Torpedo Tube: This was the "smoking gun" for Ballard's team. It’s made of metal that resisted the corrosive power of the sea.

- The Engine Remains: Deep-sea photos show the massive blocks of the Packard V-12 engines. These were the heart of the boat, and they are now silent, encrusted in a thin layer of sediment.

- The Missing Bow: You won't find the bow in the primary wreck site photos. After the collision, the bow section actually stayed afloat for several hours. It’s what the survivors clung to before swimming toward Plum Pudding Island. Eventually, it drifted away and sank somewhere else. It’s likely gone forever.

The depth is a major factor here. At 1,200 feet, there is no light. The ROV lights have to cut through "marine snow"—bits of organic matter falling from the surface—to illuminate the wreckage. This gives the pictures a snowy, ethereal quality. It feels less like a historical site and more like a crime scene.

The Controversy of the Identification

Not everyone was convinced at first. Some naval historians argued that the debris could have been from any number of PT boats lost in the Solomons. The "Slot" was a busy place during the war.

But the evidence in the PT 109 wreck pictures was hard to ignore. The location matched the historical logs of the Amagiri and the accounts of the survivors. Ballard also consulted with Dale Helmer, a PT boat expert, to verify the specific configuration of the torpedo tubes. The 109 had a unique setup because Kennedy’s crew had bolted a 37mm anti-tank gun to the foredeck just before the mission. While the gun itself hasn't been clearly photographed in a way that identifies it, the overall footprint of the debris fits the 109 perfectly.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

There's a somberness to these photos. Two men, Andrew Jackson Kirksey and Harold William Marney, died instantly when the boat was struck. Their remains were never recovered. Because of this, the site is treated as a war grave. The US Navy and the Kennedy family requested that the site not be disturbed. No artifacts were brought to the surface. No "souvenirs" were taken. The pictures are all we have.

How the Wreckage Changed the Narrative

For a long time, the story of PT 109 was told as a glossy, heroic epic. Cliff Robertson played JFK in the movies. It was all very Hollywood. But looking at the actual PT 109 wreck pictures forces a more grounded perspective.

It reminds us that these were essentially plywood "mosquito boats" going up against steel destroyers. It was an asymmetrical fight. The wreckage shows the vulnerability of the crew. When you see the mangled metal, you realize it’s a miracle anyone survived at all. Kennedy’s feat of towing a burned crewman (Patrick McMahon) by a life jacket strap held in his teeth for miles is impressive on paper. It’s unfathomable when you see the environment where it happened.

The water is dark. The currents are ripping. The wreckage is miles from any significant landmass.

Why We Don't Have More Pictures

You might wonder why there aren't high-definition, 4K videos of the wreck circulating on YouTube every day. There are a few reasons:

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

- Cost: Sending an expedition to that part of the Solomon Islands is incredibly expensive.

- Ethics: The Navy is very protective of sunken vessels. They don't want "wreck hunters" turning a grave site into a tourist attraction.

- Visibility: The silt on the bottom is easily disturbed. One wrong move by an ROV thruster and the entire site is obscured by a cloud of mud for hours.

Technical Realities of Deep Sea Photography

Taking PT 109 wreck pictures isn't like snapping a photo with your iPhone. The pressure at that depth is roughly 40 times what we feel at sea level. The camera housings have to be made of thick titanium or specialized synthetics.

The "backscatter" is the biggest enemy. If the flash is too close to the lens, the light bounces off the particles in the water and creates a white blur. Ballard’s team used "lighting platforms" that were separated from the camera to create shadows and depth. This is why the images of the torpedo tubes look so three-dimensional. They weren't just taking photos; they were mapping a tragedy in three dimensions.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're fascinated by the PT 109 story and want to dive deeper into the visual history, here is how you can actually engage with the material without becoming a deep-sea diver:

- Visit the JFK Library Digital Archives: They hold the most extensive collection of "before" photos. Comparing the pristine boat in port to the PT 109 wreck pictures from the bottom of the sea provides a jarring sense of scale and destruction.

- Study the Side-Scan Sonar Maps: National Geographic released the original sonar maps from the 2002 expedition. These are arguably more interesting than the photos because they show the "debris trail"—the path the boat took as it disintegrated.

- Check the Naval History and Heritage Command: They provide the official wreck reports. Reading the technical descriptions of the damage while looking at the photos helps you understand exactly which part of the hull you’re seeing.

- Support Marine Archaeology: Organizations like the SEARCH group continue to look for lost vessels. These missions are often the only way we get closure on "missing in action" cases from WWII.

The wreckage of PT 109 isn't just a pile of junk in the Solomon Islands. It's a physical link to a moment that changed American history. If Kennedy hadn't survived that night—if he hadn't been a strong enough swimmer or if the Amagiri had hit him five feet further back—the 1960s would have looked very different. Those pictures are a snapshot of a turning point, frozen in the dark, under a thousand feet of water.

The debris is slowly being claimed by the ocean. Eventually, even the metal will succumb to the salt and the pressure. For now, those few images remain our only window into the night the future president almost disappeared.