If you look for Iwo Jima on a map, you’re probably going to need to zoom in. A lot. It’s barely a smudge in the vast, blue emptiness of the Pacific Ocean. Just an eight-square-mile volcanic rock sitting about 750 miles south of Tokyo. Honestly, it looks like a teardrop or a burnt pork chop depending on how much coffee you’ve had. But for thirty-six days in 1945, this tiny, sulfurous crust of land was the most expensive real estate on the planet.

Most people think they know the story because of the flag-raising photo. They think of the grit and the Marines. But when you actually stare at the coordinates—$24.7539° N, 141.3271° E$—you start to realize the sheer isolation of the place. It’s part of the Volcano Islands, a chain that’s basically the jagged spine of an underwater mountain range.

There is no natural water. No trees to speak of back then, just scrub and volcanic ash. Yet, because of its specific location on the map, thousands of men died for it.

Where Exactly is Iwo Jima on a Map?

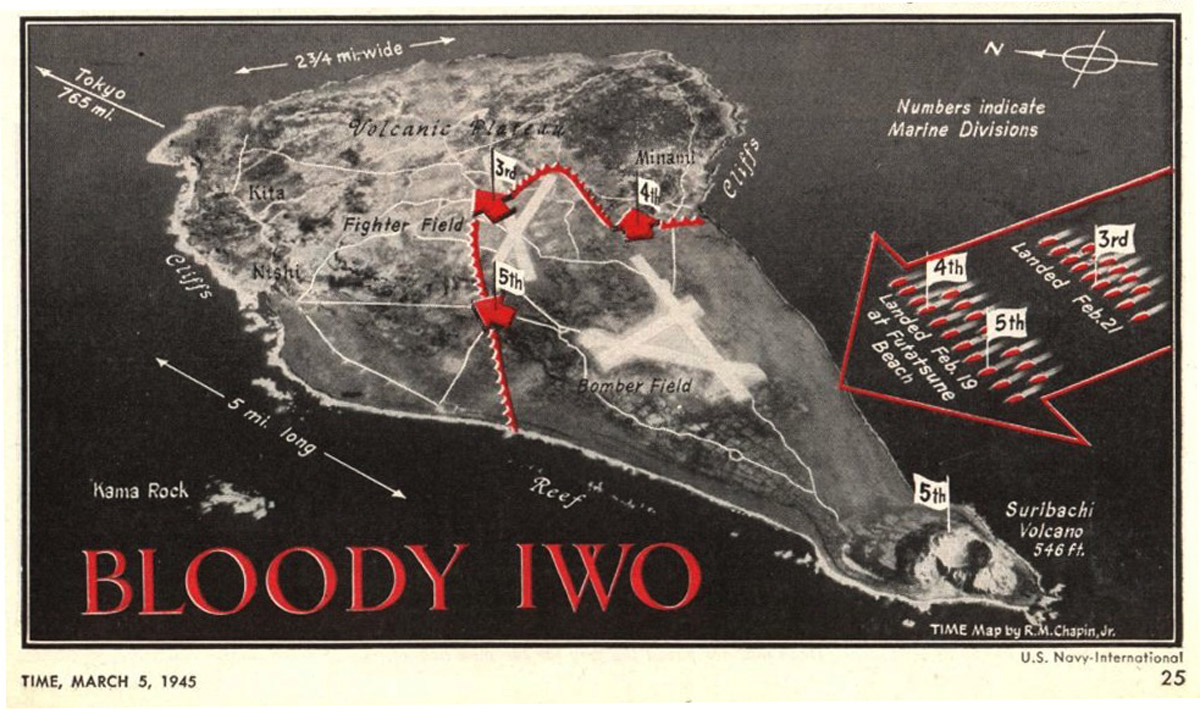

To understand why the U.S. military was so obsessed with this place, you have to look at the "Point A to Point B" of B-29 bomber runs. In 1944, American long-range bombers were flying out of the Mariana Islands—places like Saipan and Tinian. Their target was Tokyo.

It was a 1,500-mile trip. One way.

If a plane got hit over Japan or had engine trouble, there was nowhere to land. They were ditching in the ocean, and in the 1940s, "ditching" usually meant you weren't coming home. Iwo Jima sat almost exactly halfway between the Marianas and mainland Japan. For the Japanese, it was an early warning station. They’d see the planes coming and radio Tokyo: "Hey, get the fighters ready." For the Americans, it was a potential emergency landing strip and a base for P-51 Mustang escorts.

The island is dominated by Mount Suribachi at the southern tip. When you see it on a topographic map, Suribachi looks like a pimple on the end of a long, flat face. That "face" is the plateau where the airfields were built. The Japanese, led by General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, didn't fight on the beach like they did at Tarawa. They fought from inside the map. They dug 11 miles of tunnels. They turned the island into a literal honeycomb of death.

The Geology of a Nightmare

The sand isn't sand. It’s volcanic ash. Black, soft, and bottomless.

When the Marines landed, they found they couldn't run. Their boots sank past the ankles. Tanks churned in place, belly-deep in the grit, becoming sitting ducks for the Japanese artillery hidden in the cliffs of Suribachi. If you look at a modern satellite view of Iwo Jima on a map, you can still see the brownish-black tint of the shoreline. It’s a stark contrast to the white-sand tropical paradises you see in travel brochures for the Caribbean.

It’s hot there, too. Not just tropical heat, but geothermal heat. Steam vents—fumaroles—hissed out of the ground. Soldiers digging foxholes would find the earth too hot to touch. It’s a miserable, stinking place that smells like rotten eggs because of the sulfur. In fact, the name Iwo To (the current official name) literally means "Sulfur Island."

Changing the Name: Iwo Jima vs. Iwo To

Names change. Maps change.

Before the war, the few hundred civilians living there called it Iwo To. The "Jima" part came from a misreading of the kanji characters by Japanese naval officers and later the Americans. In 2007, the Japanese government officially changed the name back to Iwo To at the request of the original inhabitants' descendants.

✨ Don't miss: Flights from Tampa to Honolulu HI: What Most People Get Wrong

You’ll still see it as Iwo Jima on most Western historical maps, though. It’s one of those things where the history is so heavy that the old name just sticks.

Today, if you try to visit, you’re basically out of luck unless you’re with a military pilgrimage. It’s a restricted base for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. There are no hotels. No restaurants. No gift shops selling "I climbed Suribachi" t-shirts. It’s a graveyard. Over 21,000 Japanese soldiers died there, and the remains of roughly half of them are still there, sealed in collapsed tunnels. On the American side, nearly 7,000 men were lost.

The weight of those numbers on such a small piece of land is hard to wrap your head around.

Logistics of the Modern Map

If you’re looking at Google Maps right now, you’ll notice the runway. It’s a massive, paved strip that takes up a huge chunk of the island's flat northern area.

- Distance to Tokyo: ~1,200 km (750 miles)

- Distance to Guam: ~1,200 km

- Surface Area: 21 square kilometers

It’s essentially a stationary aircraft carrier. That was its value in 1945, and strategically, that's why it remains important to the Japanese military today. It sits in a position that monitors the Philippine Sea and the approaches to the main islands of Japan.

Why the Location Mattered to the B-29s

Some historians argue about whether the island was actually "worth it."

The "emergency landing" stat is often cited: 2,251 B-29s landed on Iwo Jima by the end of the war. With 11 men per crew, that’s 24,761 airmen. People say the battle saved their lives.

It’s more complicated than that.

Many of those landings weren't "we're going to crash" emergencies; they were "we have a funky gauge and I'd rather land here than risk the ocean" stops. But the psychological boost for the flyers was massive. Knowing that Iwo Jima on a map was there—a solid piece of ground in a thousand miles of water—changed how they flew.

It also allowed for the "P-51 escort." Before Iwo was taken, the big bombers had to fly without fighter protection. Once the Marines secured the airfields, the Mustangs could take off from Iwo, meet the bombers mid-way, and protect them over Tokyo. This decimated the Japanese air defense.

Exploring the Island via Satellite

When you toggle to the satellite view, look at the northern end. You’ll see jagged, rocky terrain. That’s the Motoyama Plateau. This is where the heaviest fighting happened after Suribachi was taken.

The Japanese didn't just dig holes; they built underground hospitals, command centers, and barracks with electricity and ventilation. When you look at the map and see the distances between the ridges, remember that every yard was a pillbox. Every cave had a line of sight to another cave.

The U.S. Navy spent weeks shelling the island before the landing. They thought they'd flattened it. They hadn't. The Japanese were twenty feet underground, just waiting for the shelling to stop. When the Marines hit the beach, the island looked dead. Then the "dead" island started shooting back.

Common Misconceptions About the Map Location

A lot of people mix up Iwo Jima with Okinawa or Guadalcanal.

Guadalcanal is way down south near Australia. Okinawa is much closer to Taiwan. Iwo Jima is out there in the "empty" part of the Western Pacific. It’s part of the Ogasawara Administration, which is technically part of Tokyo. If you were a resident of Iwo Jima today, you’d technically be living in a suburb of Tokyo, despite being a two-hour flight away.

Another weird thing? The island is growing.

Because it’s a volcano, the ground is actually rising. This is called "uplift." Since 1945, the island has risen by several meters. Some of the sunken ships that were used to create a breakwater after the battle are now sitting high and dry on the land. The map of the island today is physically larger than the map used by General Smith and Admiral Spruance in 1945.

What to Do If You're a History Buff

You can't just book a flight on Expedia. You’ve got a few very specific options:

- Military Charters: The "Reunion of Honor" happens once a year. It's a joint ceremony for veterans and families from both the U.S. and Japan.

- Civic Tours: Occasionally, specialized history tour groups (like Military Historical Tours) get permission to fly in for a day trip. You fly in, walk the beach, go up Suribachi, and fly out. No staying overnight.

- Digital Exploration: Use the 3D view on Google Earth. You can actually "climb" Suribachi virtually. Look at the western beaches. That’s where the landing craft hit. You can see how the terrain rises sharply, giving the defenders a perfect view of the slaughter.

The Actionable Reality

If you're researching Iwo Jima on a map for a project, a trip, or just personal interest, the biggest takeaway is the scale.

💡 You might also like: Why The Hotel Roanoke & Conference Center Still Defines Virginia Hospitality

Look at the distance between the beach and the airfields. It's less than two miles. It took the Marines weeks to cover that distance. Think about that. Weeks to move two miles.

If you want to dive deeper, don't just look at the land. Look at the bathymetry—the underwater map. You’ll see that Iwo Jima is just the tip of a massive volcanic system. The water drops off to thousands of feet deep almost immediately. There's no coral reef to protect the beach, which is why the surf is so violent and why the landing was such a logistical nightmare.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Check the "Shipwreck" Coast: Zoom into the western shoreline on a high-res satellite map. You can still see the rusted outlines of the "Blockships" (old concrete freighters) the U.S. intentionally sank to create a harbor.

- Compare 1945 vs. 2026: Find a "Map 1" (the invasion map) and overlay it with a modern satellite view. You’ll see how much the island has physically expanded due to volcanic activity.

- Read the Letters: If you want the human version of the map, find "Letters from Iwo Jima" (the book by Kumiko Kakehashi). It gives the Japanese perspective of being trapped on that tiny map coordinates with no hope of escape.

The map tells you where it happened, but the geology tells you why it was so hard. It’s a 1:1 scale monument to endurance. Whether you call it Iwo Jima or Iwo To, it remains a lonely, haunting spot that proves the most important places on Earth aren't always the biggest.