Honestly, if you’ve ever tried to find a clear, accurate image of woman anatomy online, you know it’s a bit of a minefield. You either get these hyper-stylized illustrations that look like they belong in a 1950s textbook or incredibly complex diagrams that require a medical degree just to label the pelvis. It's frustrating. We live in an era where information is everywhere, yet the basic understanding of the female body remains shrouded in weird euphemisms or clinical coldness.

The reality is that anatomical literacy matters. It’s not just for doctors. When you can visualize what’s happening inside—whether it’s the placement of the uterus relative to the bladder or how the pelvic floor muscles actually cradle your organs—you advocate for your health better. You ask better questions at the OB-GYN. You stop worrying about things that are actually totally normal.

Why Most Anatomy Diagrams Feel "Off"

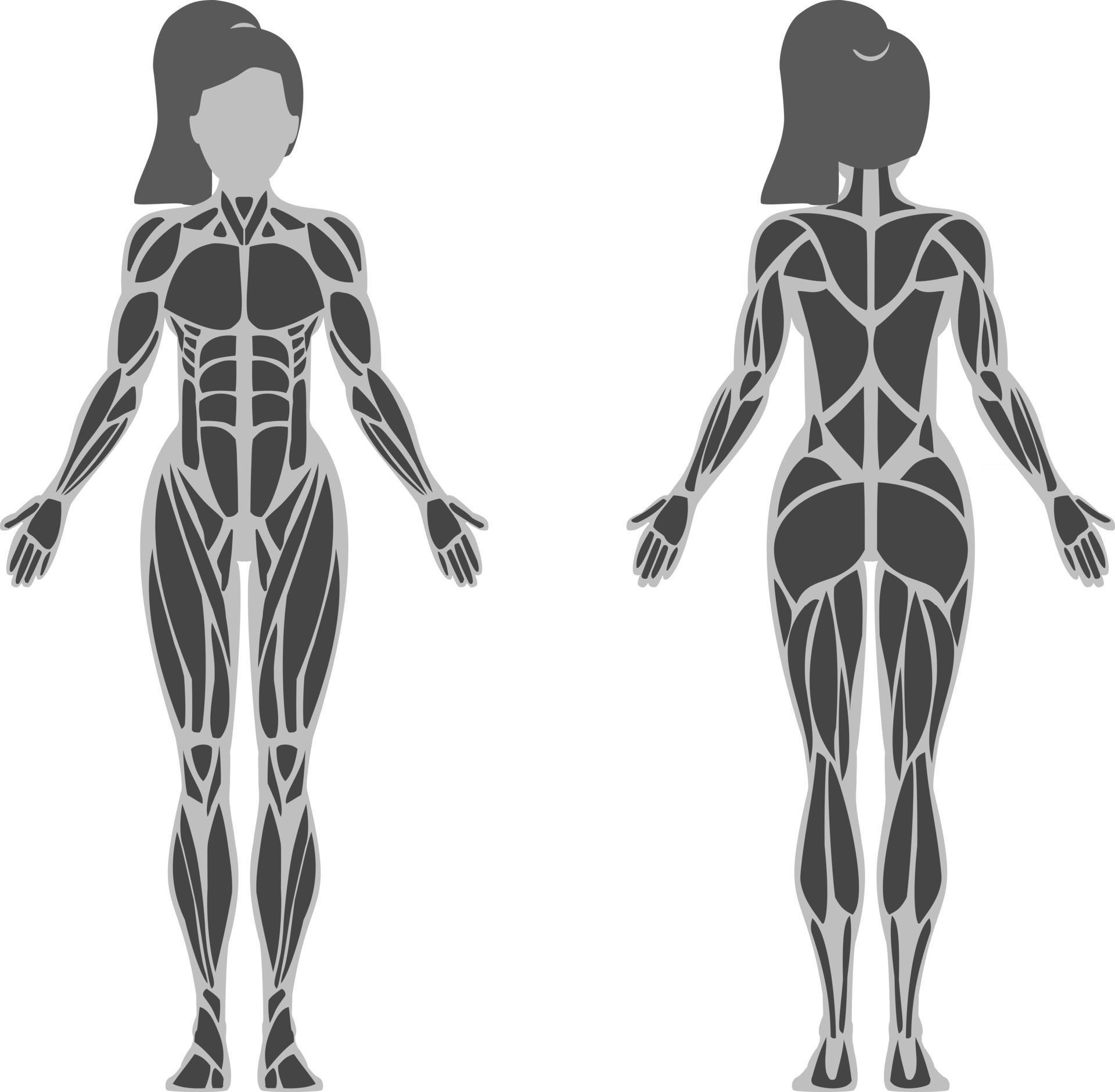

Have you noticed how many diagrams are still based on a "default" male model with female parts just sort of swapped in? It’s a systemic issue. Historically, medical illustration relied heavily on the male form as the standard. This means an image of woman anatomy often misses the nuances of volume, space, and the shifting nature of these organs.

Organs aren't static. They move. A bladder looks different when it's full versus empty. A uterus changes shape and position during a menstrual cycle, and it definitely changes during pregnancy. Most static images fail to capture this "living" aspect of anatomy. They make everything look like it’s bolted into place, but it’s more like a crowded suitcase where everything is squished together and affecting everything else.

The Pelvic Floor: More Than Just "Kegels"

People talk about the pelvic floor like it’s a single rubber band. It’s not. It’s a complex, multi-layered hammock of muscles. When you look at a high-quality image of woman anatomy from a bird's-eye view—looking down into the pelvis—you see a sophisticated web. These muscles support the weight of the bladder, the uterus, and the bowel.

If you’ve ever dealt with "leaking" when you sneeze or chronic lower back pain, the culprit is often found in these muscles. Experts like Dr. Jen Gunter have frequently pointed out that we oversimplify this area. It’s not just about "tightening." Sometimes these muscles are too tight (hypertonic) and need to learn how to relax. You can’t understand that concept until you see how they attach to the pubic bone and the tailbone.

👉 See also: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

Internal Organs and the Myth of "Empty Space"

There is zero empty space in the human abdomen. None.

When you see a 3D image of woman anatomy, the most striking thing is how the small intestine just fills every available gap. The uterus sits right between the bladder (in front) and the rectum (in back). This explains a lot. It explains why you have to pee every five minutes during your period—the uterus is slightly inflamed or contracting, and it’s literally pressing against your bladder. It explains why some people get "period poops" because of the hormonal proximity of the bowel to the uterine wall.

- The Uterus: Typically the size of a small pear, but incredibly muscular.

- The Ovaries: Not actually "attached" to the fallopian tubes like they’re glued on; the tubes have finger-like projections called fimbriae that "catch" the egg.

- The Cervix: The "gatekeeper" that changes texture and position throughout the month.

It's dynamic. It's crowded. It’s a masterpiece of biological engineering that has to be flexible enough to expand a thousand times its size during gestation and then snap back.

The Clitoris: The Full Picture

We need to talk about the fact that most people—and even some older medical textbooks—only represent the clitoris as a tiny pea-sized nub. That’s just the glans. It’s the tip of the iceberg.

A modern, accurate image of woman anatomy shows that the clitoris is actually a large, wishbone-shaped organ that wraps around the vaginal opening. It has "legs" (crura) and bulbs that engorge with blood. It’s roughly 9 to 12 centimeters long. This wasn't even widely mapped until the late 90s by researchers like Dr. Helen O'Connell. If your reference material doesn't show this internal structure, it’s outdated. Period.

✨ Don't miss: Why Doing Leg Lifts on a Pull Up Bar is Harder Than You Think

Navigating the Visuals: What to Look For

If you are searching for images for educational purposes, stop using generic search engines and start looking at dedicated medical repositories.

- Netter’s Anatomy: This is the gold standard. Frank Netter’s illustrations are legendary because they have a human quality that digital renders often lack.

- Visible Body: If you want 3D models you can rotate, this is the way to go. It shows how the layers of fascia (connective tissue) hold everything together.

- The Vagina Museum (UK): They provide excellent, science-backed visual guides that strip away the shame and focus on the fascinating biology.

Addressing the "Normal" Variance

Standardized images are helpful, but they can also create "anatomy anxiety." You might see an image of woman anatomy and think, "Wait, mine doesn't look like that."

Labiaplasty is one of the fastest-growing plastic surgeries because people see "perfect" diagrams and think their own natural variation is a deformity. It’s not. Labia come in all shapes, sizes, and colors. Ovaries can be slightly asymmetrical. Uteruses can be "tilted" or "retroverted," which sounds like a medical condition but is actually just a normal variation for about 20% of the population.

Actionable Steps for Anatomical Literacy

If you want to actually use this information to improve your life, don't just look at a picture and move on.

Map your own cycle to the visuals.

When you feel ovulation pain (mittelschmerz), look at a diagram of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Visualize where that follicle is. It makes the sensation less "scary" and more "process-oriented."

🔗 Read more: Why That Reddit Blackhead on Nose That Won’t Pop Might Not Actually Be a Blackhead

Use the right terminology with your doctor.

Instead of saying "down there" or "my stomach," use the terms you see in a verified image of woman anatomy. Say "pelvic floor," "cervix," or "vulva." It changes the dynamic of your healthcare. You become a partner in your care rather than just a passive patient.

Check your sources.

If you're looking at an image on a "wellness" blog that is trying to sell you a detox tea, be skeptical. If the image is from a university, a reputable medical journal (like The Lancet or JAMA), or a specialized anatomy app, it's much more likely to be anatomically correct.

Understand the link between the core and the floor.

Your diaphragm (the muscle under your lungs) and your pelvic floor move in tandem. When you breathe in, both should drop. When you breathe out, both lift. Visualizing this "piston" movement can help with everything from lifting heavy weights to managing stress.

Anatomy isn't a static map; it's a blueprint for how you move through the world. The more you look at accurate representations, the more you realize that the female body isn't a "variation" of the male one—it's a distinct, highly optimized system with its own rules, its own strengths, and its own incredible capacity for change. Stop settling for simplified diagrams. Look for the complexity, because that’s where the real understanding lives.