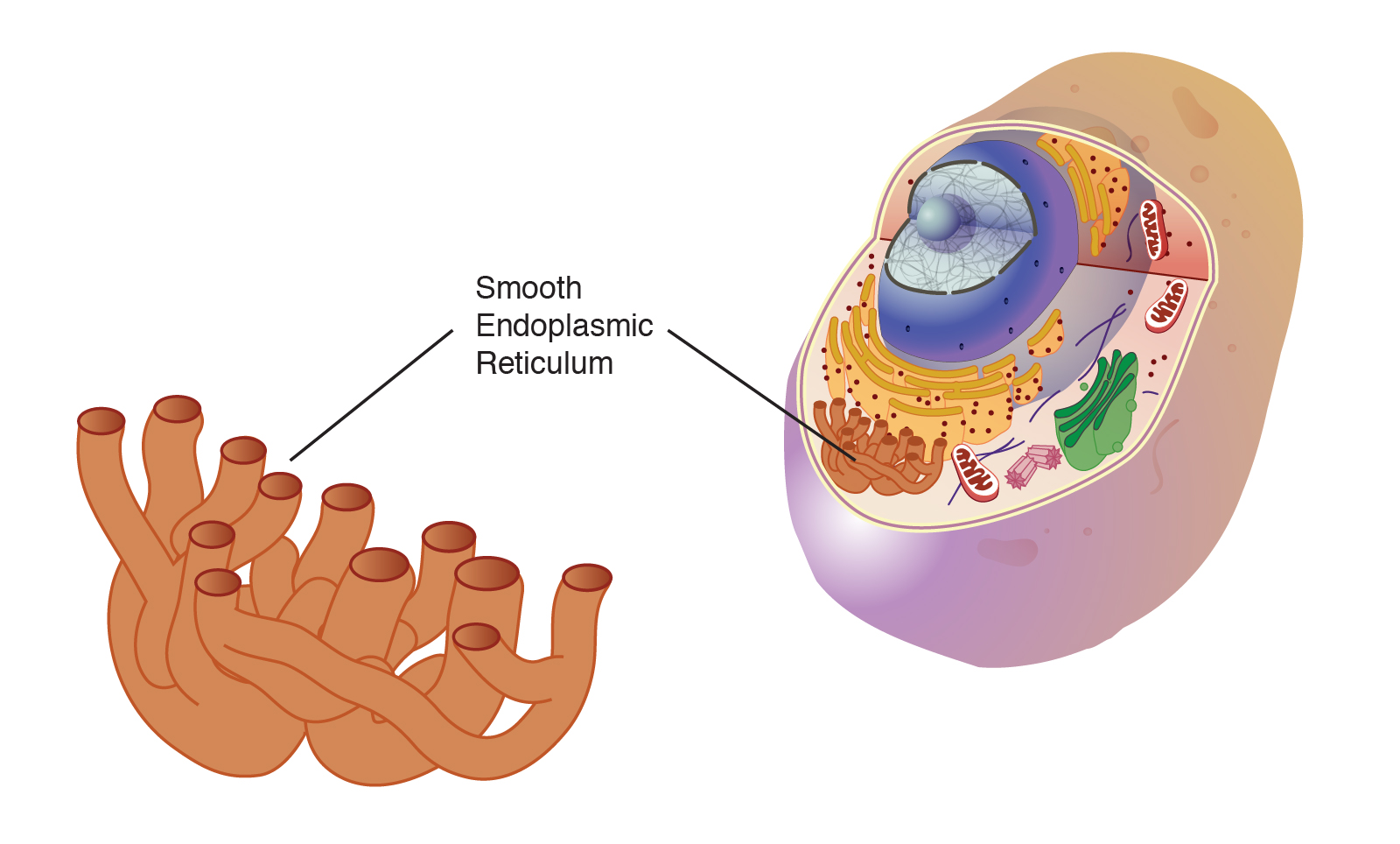

You’ve seen the drawings. Those neon-pink, wavy tubes huddled next to the nucleus in every high school biology book since 1995. They look like a pile of coral or maybe some discarded linguine. But if you actually go looking for a smooth endoplasmic reticulum image captured via electron microscopy, reality looks a lot messier. And honestly, it’s way more interesting than the simplified cartoons suggest.

The smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) is the cellular equivalent of a specialized factory floor that doesn't use heavy machinery. While its cousin, the Rough ER, is covered in ribosomes—those little protein-making dots that give it a sandpaper look—the SER is sleek. It’s a branching network of tubules and vesicles. It’s where your body handles the "greasy" stuff: lipids, steroids, and detoxifying the literal poisons you put in your body.

The Trouble With Your Average Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum Image

Most people search for a smooth endoplasmic reticulum image expecting a clear, isolated structure. They want to see a single organelle sitting by itself. But cells are incredibly crowded. In a real Transmission Electron Micrograph (TEM), the SER is often just a tangled web of faint lines and circles tucked between mitochondria and the much more obvious Rough ER.

Because the SER lacks those dark, electron-dense ribosomes, it often fades into the background of a grayscale micrograph. Scientists often have to use "false coloring" to help students identify it. If you're looking at a black-and-white scan, you have to look for the "tubular" nature. While the Rough ER looks like flat pancakes (cisternae), the SER looks more like a messy pile of pipes.

It's not just for show, either. The shape dictates the function. These tubes provide a massive surface area for enzymes to do their work without taking up too much room. Think of it like the heat exchange coils on the back of an old fridge. Maximizing surface area in a tiny 3D space is the name of the game here.

What's Actually Happening Inside Those Tubes?

If you could zoom into a high-resolution smooth endoplasmic reticulum image, you wouldn't see much movement, but the chemical activity is staggering. The SER is the primary site for lipid synthesis. This means every bit of cholesterol in your body and the phospholipids that make up your cell membranes are born here.

It’s a literal pharmacy

In your liver cells (hepatocytes), the SER is massive. Why? Because that’s where detoxification happens. When you take an aspirin or have a glass of wine, the enzymes in the SER go to work. Specifically, the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes. They take fat-soluble toxins—which are hard for the body to get rid of—and make them water-soluble so you can pee them out.

It's a adaptive system. If you drink heavily and consistently, your liver cells will actually grow more smooth ER. They physically expand to handle the load. This is why "tolerance" happens. Your cells literally build more factory space to process the alcohol faster. However, this comes at a cost. Sometimes the SER gets so overworked that it starts producing "reactive oxygen species," which is a fancy way of saying it creates chemical trash that damages the cell.

Muscle memory and calcium

If you look at a smooth endoplasmic reticulum image from a muscle cell, scientists usually call it the sarcoplasmic reticulum. It’s the same basic structure but with a hyper-specific job: hoarding calcium ions. When you want to move your arm, your nerves signal the SER to dump all that calcium into the cell. This triggers the muscle fibers to slide past each other. When you relax, the SER pumps the calcium back inside. Without this "calcium battery," you'd be a literal puddle.

Why Quality Images are Hard to Find

Most of the "cool" photos you see online are actually 3D reconstructions. Scientists take hundreds of 2D slices from an electron microscope and stack them using software. It’s a bit like a CT scan for a cell. Dr. Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute has done some incredible work using "super-resolution microscopy" to show how the SER isn't just a static pile of tubes. It’s constantly shifting, sliding, and remodeling itself.

🔗 Read more: Why Most People Get Motion Detector for Lights Installations Wrong

Older images made the ER look like a permanent fixture, like the plumbing in your house. New tech shows it’s more like a crowd of people at a concert—constantly moving, breaking apart, and fusing back together.

Spotting the SER: A Quick Checklist

When you are scrolling through a database like the Cell Image Library or looking at a biological paper, here is how you tell you're actually looking at a smooth endoplasmic reticulum image and not just some random cellular junk:

- Check for "Dots": If the tubes have little black specks on them, it’s Rough ER. The Smooth ER must be "naked."

- Look for Loops: SER tends to form "anastomosing" networks. That’s a nerd word for tubes that connect back into themselves, forming loops.

- Proximity to Mitochondria: Since the SER is involved in lipid metabolism and signaling, it’s often found snuggling up very close to mitochondria. They share "contact sites" to swap lipids and calcium.

- Vesicle Presence: You’ll often see tiny bubbles (vesicles) budding off the SER. These are the "delivery trucks" carrying newly made fats to the Golgi apparatus or the cell membrane.

The Evolutionary "Why"

Why have two different types of ER? It’s all about compartmentalization. Cells are chaotic. If you have protein synthesis (which requires a lot of water and specific pH levels) happening in the exact same spot as lipid synthesis (which is oily and hydrophobic), they’d interfere with each other. By separating the "rough" and "smooth" sections, the cell can create two totally different chemical environments just nanometers apart.

It’s also an energy-saving move. By keeping the SER enzymes localized, the cell doesn't have to flood the entire cytoplasm with chemicals. It just keeps them concentrated inside the tubules.

To get the most out of your study of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, don't just rely on the first diagram you see in a Google search. Search specifically for "Transmission Electron Micrograph Smooth ER" to see the raw, unedited reality of cellular biology. Cross-reference those images with diagrams from reputable sources like the Molecular Biology of the Cell (Alberts et al.) to understand how the 2D "lines" you see in a photo translate to the 3D "tubes" that keep you alive. If you're a student, try sketching a micrograph yourself; it's the fastest way to train your eyes to see the subtle textures that define different organelles.