Math is everywhere. We see it in the way skyscraper windows align and in the sharp corners of a fresh sheet of paper. But honestly, when you search for a picture of a perpendicular line, you usually get these sterile, digital diagrams that feel totally disconnected from the real world. They’re just two black sticks crossing at a right angle on a white background. It’s boring. It’s also kinda misleading because perpendicularity isn't just a concept in a geometry textbook; it’s the literal backbone of how we build things that don't fall over.

You’ve probably seen the symbol $\perp$ before. That’s the shorthand. If you were to look at a picture of a perpendicular line in a professional drafting setting, you’d see a tiny little square tucked into the corner where the lines meet. That’s the universal "yep, this is 90 degrees" sign.

But why does it matter? If a carpenter is framing a house and their vertical studs aren’t perpendicular to the floor joists, the whole structure starts to lean. This is called being "out of plumb." Gravity is a relentless jerk, and it’s constantly trying to pull things down. Perpendicular lines are the only way to ensure that weight is distributed directly toward the earth’s center.

The visual anatomy of 90 degrees

When you’re looking at a picture of a perpendicular line, you’re seeing an intersection. Two lines meet, and they create four right angles. If any of those angles is $89.9^\circ$ or $90.1^\circ$, they aren't perpendicular. They’re just intersecting.

Precision matters. In high-end manufacturing, like at companies such as Zeiss or Mitutoyo, they use coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) to verify perpendicularity down to the micron. It’s wild. Think about the screen on your phone. If the internal grid of transistors wasn’t perfectly perpendicular, the pixels would be skewed, and your high-definition movies would look like a Funhouse mirror.

👉 See also: Campbell Hall Virginia Tech Explained (Simply)

Most people confuse "perpendicular" with "vertical." They aren’t the same thing. A line can be slanted at a 45-degree angle, and as long as another line hits it at a perfect right angle, they are perpendicular to each other. Orientation doesn't change the relationship.

Where to find a picture of a perpendicular line in your house

Stop reading for a second. Look at your door frame. See that corner? That’s it. That’s the real-world picture of a perpendicular line you interact with every single day. If that corner wasn't a perfect $90^\circ$ angle, your door would stick. It would squeak. It would drive you absolutely insane.

- The tiles on your bathroom floor? Perpendicular.

- The legs of your kitchen table relative to the floor? Perpendicular (hopefully).

- The "T" on your keyboard? Yep, perpendicular.

Even the way we write letters relies on this. An "L" is just two perpendicular segments. A "T" is a perpendicular intersection. Our entire written language in the Latin alphabet is basically a collection of right angles and curves.

Why artists sometimes hate perfect right angles

While engineers love them, artists sometimes find a perfect picture of a perpendicular line to be a bit "static." In photography, there’s a concept called the "Dutch Angle." This is where the camera is tilted so that the horizon line isn't parallel to the bottom of the frame, which means the vertical lines of buildings are no longer perpendicular to the viewer's eye level. It creates tension. It makes you feel like something is wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Burnsville Minnesota United States: Why This South Metro Hub Isn't Just Another Suburb

Basically, we are subconsciously programmed to find comfort in perpendicularity. It represents stability. When an architect like Frank Gehry designs a building like the Walt Disney Concert Hall, it’s famous specifically because it avoids those traditional 90-degree intersections. It feels fluid and chaotic because it’s fighting against our natural expectation of a picture of a perpendicular line holding up a roof.

The math behind the image

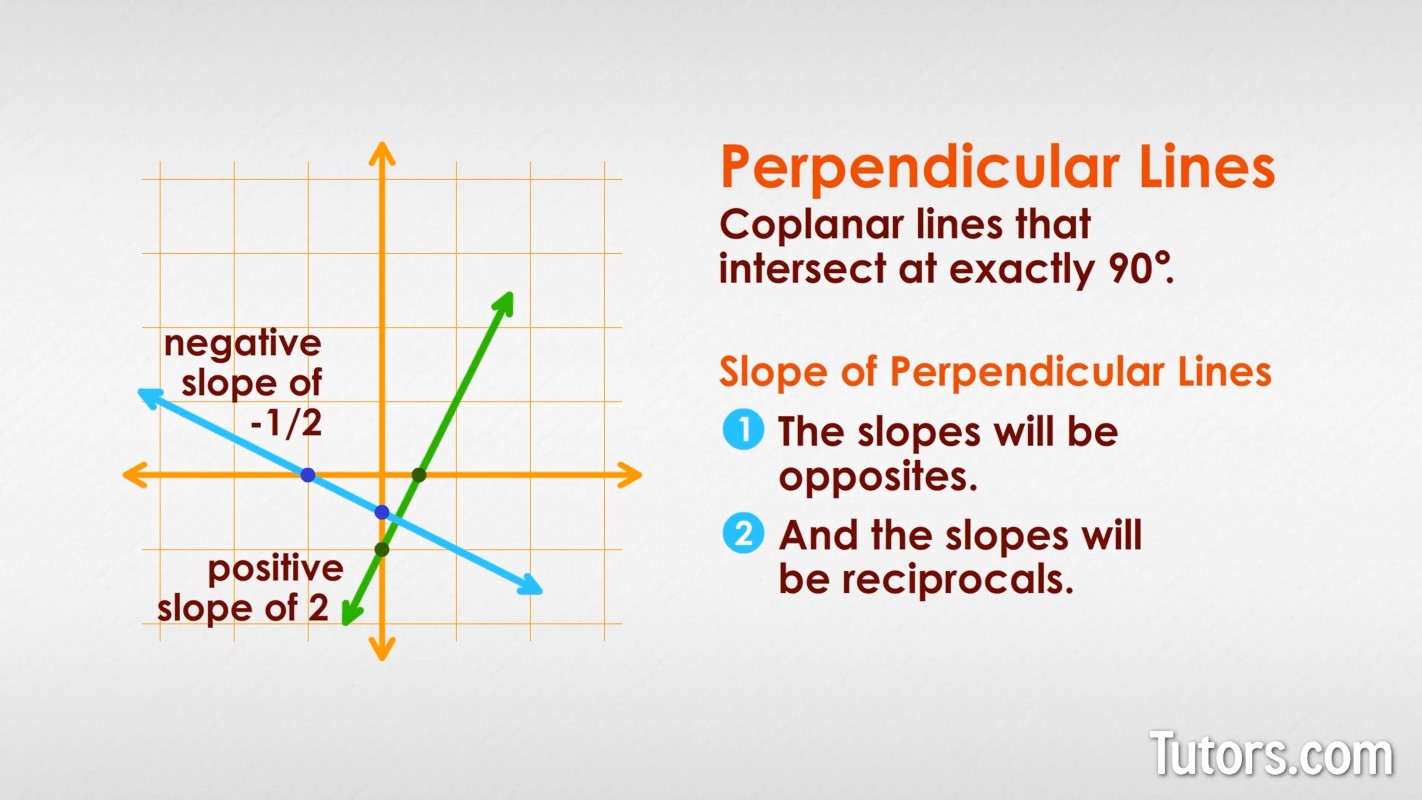

If you want to get technical—and we should—the relationship between these lines is defined by their slopes. If you have a line with a slope of $m$, the line perpendicular to it must have a slope of $-\frac{1}{m}$. This is the "negative reciprocal."

Let's say you have a line on a graph moving up 2 units for every 1 unit it moves right. Its slope is 2. To find its perpendicular partner, you flip that 2 upside down to get $1/2$ and slap a minus sign on it. So, $-1/2$. If you graphed those, you’d have a perfect picture of a perpendicular line on your screen.

Euclidean geometry, the stuff we all learned in high school from Euclid’s Elements, treats these as fundamental truths. But here’s a brain-melter: on a curved surface, like the Earth, perpendicular lines can behave weirdly. If you walk from the North Pole down to the equator, turn $90^\circ$, walk along the equator, turn $90^\circ$ again, and head back to the pole, you’ve just made a triangle with three right angles. On a flat piece of paper, that’s impossible. On a sphere? It's just Tuesday.

🔗 Read more: Bridal Hairstyles Long Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Wedding Day Look

Capturing the perfect shot

If you’re a photographer trying to take a picture of a perpendicular line in architecture, you have to worry about "keystoning." This happens when you point your camera up at a tall building. Even though the building’s corners are perpendicular to the ground, they look like they’re vanishing toward each other in your photo.

Professionals use "tilt-shift" lenses to fix this. These lenses actually slide up and down on the camera body to keep the sensor parallel to the building, ensuring the lines stay perfectly straight. It’s a literal physical correction of light to preserve that $90^\circ$ relationship.

How to use this in your own projects

If you're DIYing a shelf or building a deck, don't trust your eyes. Your eyes are liars. They get tricked by perspective and shadows. Always use a square. A "Speed Square" or a "Try Square" is basically a physical picture of a perpendicular line made of metal.

- The 3-4-5 Rule: This is the old-school contractor trick. If you measure 3 feet along one wall and 4 feet along the other, the diagonal distance between those two points (the hypotenuse) should be exactly 5 feet. If it is, your walls are perpendicular. It’s the Pythagorean theorem ($a^2 + b^2 = c^2$) in action.

- Laser Levels: For about $20, you can get a laser that shoots two perpendicular lines across a room. It’s way more accurate than a bubble level for long distances.

- Digital Protractors: These are great for checking if your miter saw is actually cutting a true 90.

Final thoughts on the humble right angle

The next time you look at a picture of a perpendicular line, don't just see two lines crossing. See the physics of gravity being countered. See the precision of modern manufacturing. See the comfort of a door that actually closes.

To apply this knowledge practically, start by checking the "squareness" of your current workspace. Use a standard sheet of paper—which is manufactured to have nearly perfect perpendicular corners—and align it with the corner of your desk or a picture frame on your wall. If you see gaps, you're looking at the difference between theoretical geometry and the messy reality of construction. For any serious project, invest in a 12-inch combination square; it's the most reliable way to turn a mental concept into a physical reality.