If you’ve ever tried searching for a picture of a ovary, you probably realized pretty quickly that the internet is a confusing mess of neon-pink medical diagrams and grainy, black-and-white ultrasound blobs. It’s weird. Most of us go through life knowing we have these almond-sized powerhouses (or knowing someone who does), yet we have almost no idea what they actually look like in the wild.

They aren't perfect, smooth pearls.

Honestly, a real ovary looks a bit like a lumpy, scarred walnut. It’s fleshy. It’s dynamic. Depending on where a person is in their menstrual cycle, that "picture" changes completely because the ovary is basically a shapeshifter.

The Reality vs. The Textbook

When you see a picture of a ovary in a high school biology book, it’s usually part of a clean, symmetrical "U" shape with the uterus and fallopian tubes. Everything is color-coded. In reality, your insides are crowded. The ovaries are tucked away in the lateral walls of the pelvis, often overshadowed by loops of bowel or the bladder.

Surgeons will tell you that finding them during a laparoscopy isn't always a straight shot. They're held in place by ligaments—the ovarian ligament and the broad ligament—but they still have a bit of "wiggle room."

The Color and Texture

A healthy ovary is typically an off-white or grayish-pink color. It has a puckered surface. Why the scars? Every time an egg is released during ovulation, it literally bursts through the surface of the ovary. This creates a tiny wound that heals into a small scar. If you’re looking at a picture of a ovary from someone who has been ovulating for twenty years, you’re looking at a landscape of many "battle scars" from successful cycles.

🔗 Read more: Necrophilia and Porn with the Dead: The Dark Reality of Post-Mortem Taboos

It’s a bit visceral.

The size is another thing people get wrong. While "almond-sized" is the standard comparison, they vary. During puberty, they’re small and smooth. During the reproductive years, they swell and shrink every month. After menopause? They atrophy. They get smaller and more fibrous, eventually becoming quiet, dormant versions of their former selves.

What a Picture of a Ovary Shows During Ovulation

This is where things get genuinely fascinating. If you take a picture of a ovary right before ovulation, it won't look like a solid mass. You'll see a bulge.

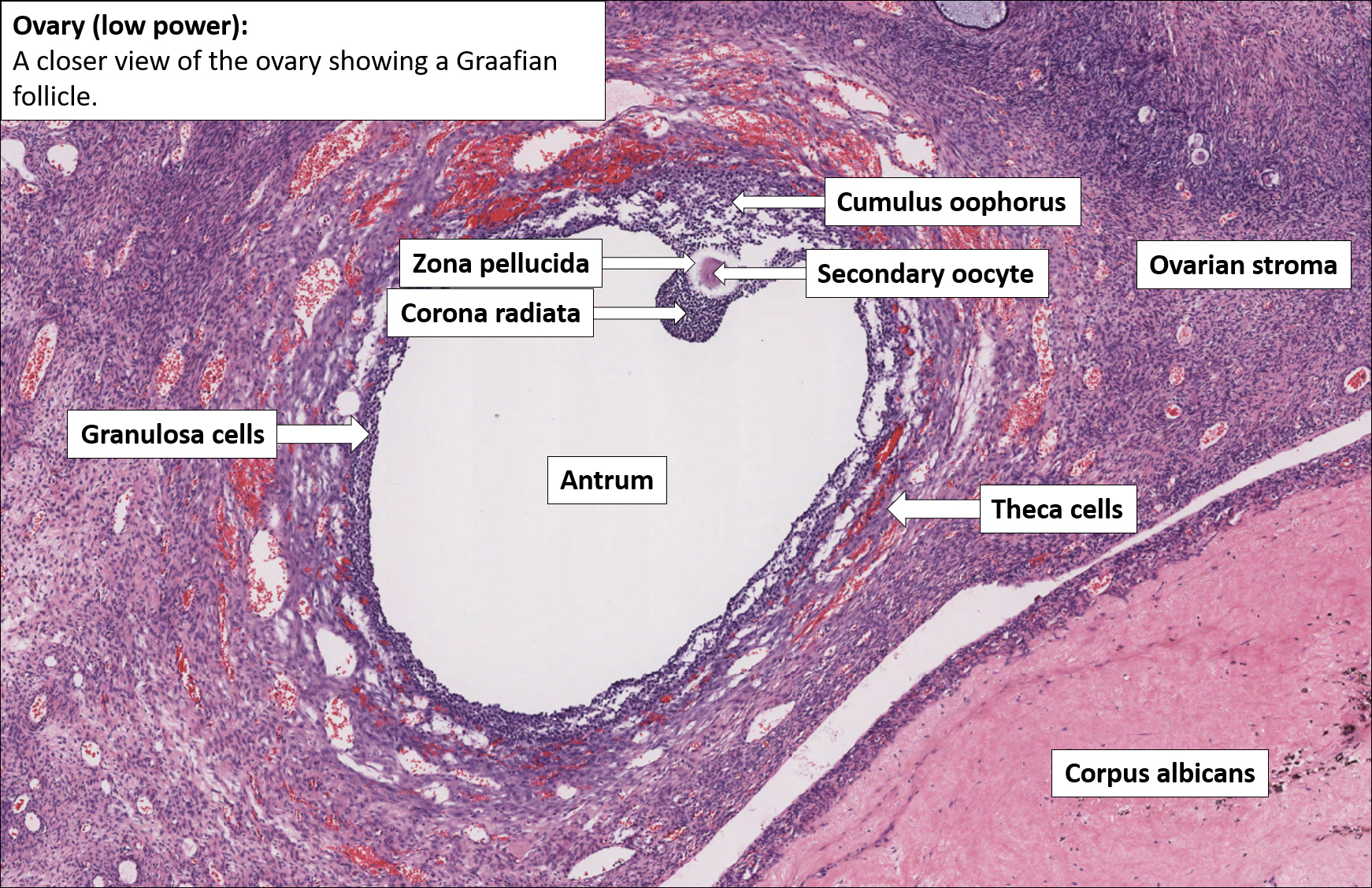

This bulge is the Graafian follicle.

Inside that follicle is the egg, surrounded by fluid. On an ultrasound—which is the most common "picture" people actually get of their own ovaries—this looks like a dark, circular void. It’s not a hole; it’s just fluid, and ultrasound waves pass right through fluid without bouncing back.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Pulse Is Racing: What Causes a High Heart Rate and When to Worry

The Corpus Luteum

After the egg is gone, the empty follicle doesn't just disappear. It collapses and transforms into the corpus luteum. In a color photograph from a surgery, this looks like a bright yellow, fatty blob on the side of the ovary. This "yellow body" is a temporary gland. It pumps out progesterone to keep a potential pregnancy stable. If no pregnancy happens, it shrivels up, turns into white scar tissue (the corpus albicans), and the cycle starts over.

Common Abnormalities in Ovarian Images

Most people search for a picture of a ovary because they’re worried about something. Maybe a doctor mentioned a cyst or "polycystic" ovaries.

- Simple Cysts: These are very common. In an image, they look like a large, clear bubble. Most are functional and go away on their own.

- Endometriomas: Often called "chocolate cysts." On a surgical picture of a ovary, these look dark and brownish because they are filled with old blood.

- PCOS (Polycystic Ovary Syndrome): This is a bit of a misnomer. In a picture of a ovary with PCOS, you don’t see large cysts. Instead, you see a "string of pearls." These are many tiny, immature follicles that got stuck and couldn't quite release an egg.

- Teratomas: These are the weirdest. Also known as dermoid cysts, they can contain hair, teeth, or sebum. A picture of a ovary with a teratoma is often used in medical school to shock students because it looks like something out of a sci-fi movie.

Why Quality Matters in Ovarian Imaging

We rely on technology to see these organs because, well, they're inside us. A standard 2D ultrasound is the "workhorse" of the OB-GYN world. It’s fast and cheap. However, it’s not always enough.

Sometimes, doctors need a 3D ultrasound or an MRI to get a better picture of a ovary if they suspect something like ovarian torsion (where the ovary twists on its blood supply) or a complex mass. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the "gold standard" for initial evaluation of the adnexa (the structures next to the uterus) remains the transvaginal ultrasound because of its proximity to the organs.

The clarity of the image depends on several factors:

📖 Related: Why the Some Work All Play Podcast is the Only Running Content You Actually Need

- The frequency of the ultrasound probe.

- The amount of gas in the patient's bowels (which blocks the view).

- The skill of the sonographer.

- The phase of the menstrual cycle.

Misconceptions About Ovarian Health and Appearance

People often think that if an ovary looks "lumpy" in a picture of a ovary, it must be cancerous. That’s rarely the case. Lumpy is actually the default state for a functioning reproductive organ.

Another myth is that you can "see" your egg count in a single picture. While an "antral follicle count" can give a doctor a rough estimate of your ovarian reserve, a single picture of a ovary is just a snapshot in time. It doesn't tell the whole story of fertility or hormonal health.

The complexity is staggering.

Dr. Jen Gunter, a well-known OB-GYN and author of The Vagina Bible, often emphasizes that the ovaries are not just "egg sacs." They are sophisticated endocrine glands. They produce estrogen, progesterone, and even testosterone. When you look at a picture of a ovary, you aren't just looking at an organ; you're looking at a chemical factory that influences everything from your bone density to your mood and skin elasticity.

What to Do if You're Concerned About an Image

If you have seen a picture of a ovary from your own medical records and you’re staring at the "impression" section of the report, don't panic. Medical terminology is notoriously scary-sounding. Words like "heterogeneous" or "hypoechoic" just describe how the tissue looks on a screen, not necessarily that something is wrong.

- Check the cycle date. If you had the image taken on day 14 of your cycle, a large "cyst" might just be the follicle you're about to ovulate.

- Ask for the "Radiology Assistant" breakdown. This is a tool many doctors use to categorize ovarian masses.

- Get a second look. If an ultrasound is unclear, an MRI is often the next logical step to get a high-definition picture of a ovary without the interference of bowel gas or pelvic bones.

Actionable Next Steps

- Track your cycle: If you need an ultrasound, try to schedule it just after your period ends (days 5-10) when ovarian activity is at its quietest. This provides the "cleanest" picture of a ovary.

- Request the actual images: Most hospitals provide a patient portal. Don't just read the report; look at the images. Even if you aren't a doctor, seeing the physical reality of your anatomy can be empowering.

- Discuss "Watchful Waiting": If an image shows a simple cyst under 5cm, many experts recommend a follow-up scan in 6-8 weeks rather than immediate surgery. Most of these resolve naturally.

- Consult a specialist: If a picture of a ovary reveals a "complex" mass, skip the general practitioner and go straight to a gynecologic oncologist or a reproductive endocrinologist for a more nuanced interpretation.