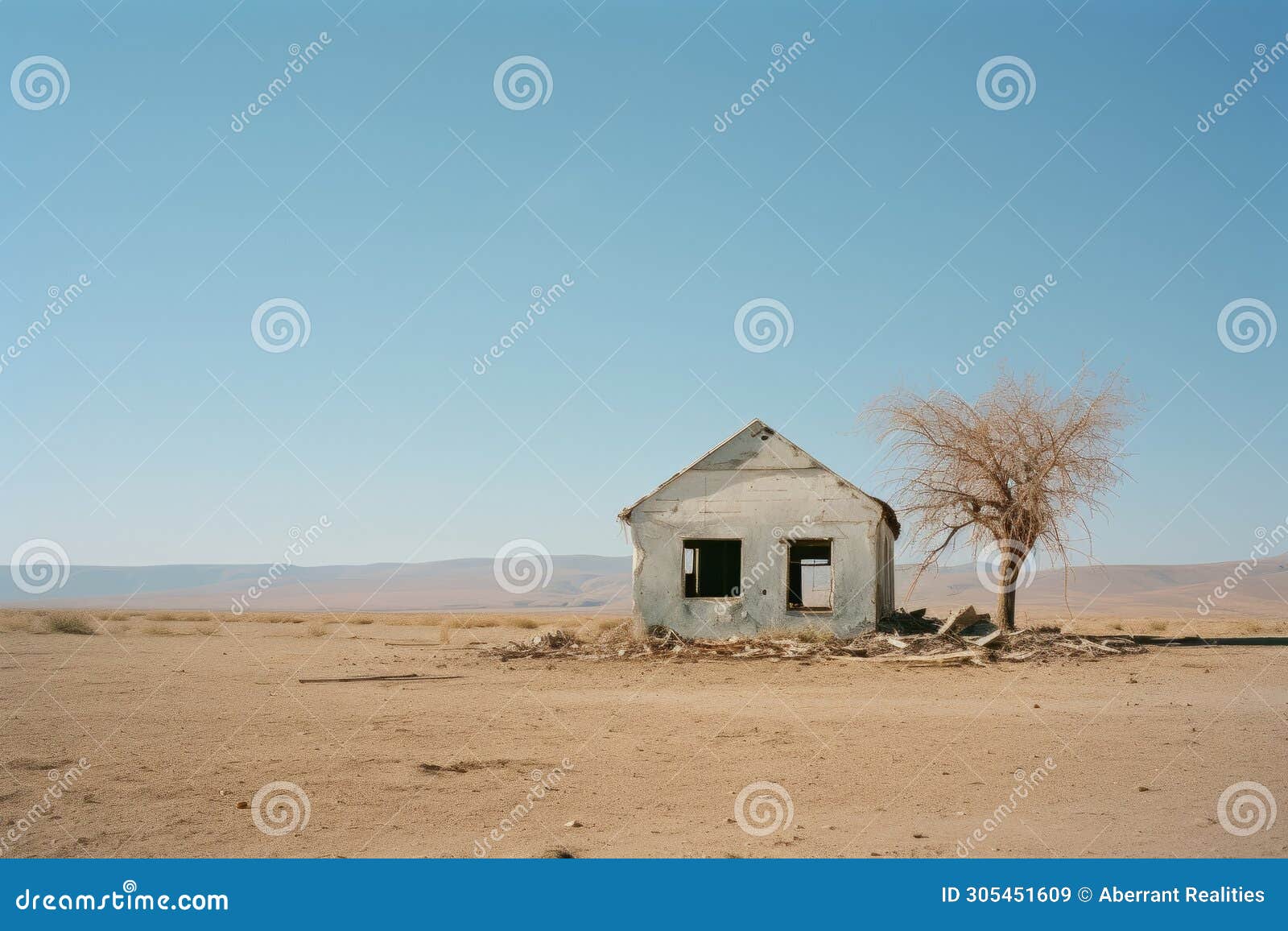

You’ve seen the photos. A tiny, weathered cabin perched on a jagged cliff in Iceland or a sleek, glass-walled box tucked into the deep woods of the Pacific Northwest. They look peaceful. Perfect, even. But buying a house in the middle of nowhere isn't just about escaping your noisy neighbors or finally having a place to see the Milky Way without light pollution. It’s a massive logistical chess game.

Most people think "remote" means a thirty-minute drive to a Target. Real remote is different. It’s the kind of isolation where the mail carrier doesn’t come to your door, and if your well pump dies on a Tuesday, you might be hauling buckets of water from a creek until Saturday.

I’ve spent years looking at these properties, talking to the people who actually live in them, and seeing where the dream hits the reality of a frozen pipe at 3:00 AM. There is a specific kind of grit required. You aren't just a homeowner anymore; you're the city manager, the waste department, and the chief of police for your own five-acre kingdom.

The Cost of Silence

Let's be real about the money. People assume a house in the middle of nowhere is cheap. Land is cheaper, sure. You can find acreage in rural West Virginia or the high desert of New Mexico for a fraction of what a suburban lot costs in Austin or Denver. But the "house" part? That's where the math gets messy.

Building out there is a nightmare. General contractors hate long commutes. If they have to drive two hours each way to get to your site, you’re paying for that windshield time. According to data from various rural development forums and construction cost indexes, mobilization fees can add 20% to your total build cost before a single nail is driven. Then there’s the "off-grid" tax. If you aren't near a municipal power line, hooking up to the grid can cost $30,000 to $50,000 per mile of poles.

Suddenly, that "cheap" $40,000 lot needs $100,000 in infrastructure just to turn on a lightbulb.

Water and Waste: The Unsexy Reality

You can’t just flush and forget. Most remote homes rely on septic systems. If you're buying an existing house, you better hope the previous owner didn't treat the leach field like a trash can. A failed septic system is a $15,000 surprise you don't want.

📖 Related: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

And water? You’re likely on a well. In places like Arizona or the Central Valley of California, wells are running dry as aquifers deplete. It’s not uncommon for homeowners to have to "drop" their pump deeper or drill a whole new well, which can cost upwards of $20,000. Always check the "well log"—it’s a public record that tells you how deep the water is and how many gallons per minute the well produces. If it’s under 3 gallons per minute, you’re going to be taking very short showers.

The Psychology of True Isolation

Loneliness hits differently when there’s no physical escape. It’s one thing to stay home for a weekend in the city. It’s another to be snowed in for ten days in a house in the middle of nowhere with nothing but the sound of the wind.

Psychologists often talk about "cabin fever," but the more technical term is related to sensory deprivation and social isolation. Humans are social animals. We’ve evolved to need mirrors—not literal ones, but other people who reflect our existence back to us. When you remove that for long periods, your internal monologue gets loud. Really loud.

Some people thrive. They write novels, they garden, they learn to fix engines. Others crack. I knew a couple who moved to the remote mountains of Montana for "peace." They lasted six months. The silence wasn't peaceful to them; it was heavy. They missed the hum of traffic and the ability to walk to a coffee shop.

Logistics: The Stuff No One Mentions

How do you get a pizza? You don't. How do you get high-speed internet? Well, Starlink changed the game for the house in the middle of nowhere, but it’s not infallible. Heavy tree cover or massive storms can still knock you offline. If you work a remote corporate job that requires 99.9% uptime for Zoom calls, you need a backup—and a backup for your backup.

- Fuel storage: You’ll likely have a massive propane tank. You have to monitor it. If you run out in mid-January, the delivery truck might not be able to get up your unplowed driveway.

- Trash: There is no garbage truck. You’re taking your stinking bags to the local "transfer station" (the dump) yourself. In your own car. Hope you have a truck.

- Emergency Services: Dialing 911 is different when the nearest deputy is 45 minutes away. You become your own first responder. This means keeping a serious first-aid kit—not just Band-Aids, but tourniquets and trauma supplies—and knowing how to use them.

The Architecture of the In-Between

Remote homes have to be built "tougher." In the city, a small roof leak is an annoyance. In a remote area, it’s a catastrophe.

👉 See also: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

Architects like Tom Kundig have made a career out of designing high-end, remote cabins that use "kinetic" elements—metal shutters that can be cranked closed to seal the house like a vault when the owners are away. This isn't just for aesthetics. It’s for protection against wildfires, bears, and extreme weather.

If you're looking at a house in the middle of nowhere, look at the "envelope." Is it fire-resistant? Does it have defensible space (a perimeter cleared of brush)? In the American West, this is the difference between a house that survives a summer and one that turns to ash.

The Myth of Self-Sufficiency

There’s this romantic idea that you’ll move out to the sticks and grow all your own food.

It’s exhausting.

I’ve seen people start with ten chickens and a massive garden, only to realize that the local coyotes, hawks, and deer view their backyard as an all-you-can-eat buffet. Real self-sufficiency takes about 40 hours of labor a week. It’s a second job. Most successful remote dwellers find a middle ground: they grow some greens, keep a few hens, but still make the hour-long trek to a warehouse club once a month to stock a massive chest freezer.

Finding "The One"

So, how do you actually find a good one? You don't look on the standard apps. Not primarily.

✨ Don't miss: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

The best remote properties often trade hands through local word-of-mouth or specialized rural land brokers like LandWatch or United Country Real Estate. You want to look for "unincorporated" land if you want fewer rules, but remember that "no rules" also applies to your neighbors. You might build your dream eco-cottage only to have a guy move in next door and start a scrap metal business. Zoning is your friend, even if it feels like "the man" telling you what to do.

A Quick Checklist for the Remote Hunter:

- Check the "Egress": Is the road public or private? If it's private, who plows it? If the answer is "the neighbors get together and do it," be prepared for drama.

- Test the Signal: Don't trust the coverage maps. Drive to the property and actually try to make a phone call.

- The "Golden Hour" Visit: Visit at dusk. That’s when you’ll hear the local dogs barking, the nearby highway you didn't know was there, or the sound of the neighbor's generator.

- Insurance: This is the big one. Many insurance companies are pulling out of high-risk fire or flood zones. You might find a beautiful house in the middle of nowhere that is literally uninsurable, or the premium is $8,000 a year.

The Reality Check

Living in a house in the middle of nowhere is a trade-off. You trade convenience for autonomy. You trade social stimulation for internal clarity. It’s not a vacation; it’s a lifestyle choice that requires a very specific set of skills: basic plumbing, some electrical knowledge, and the ability to be alone with your own thoughts without panicking.

If you can handle the fact that you are solely responsible for your own heat, water, and safety, there is nothing like it. The air is thinner, the stars are brighter, and the silence is a physical presence that eventually feels like a warm blanket rather than a void.

Practical Next Steps

If you’re serious about moving to a house in the middle of nowhere, don't buy yet.

Rent an Airbnb in a truly remote area during the worst season. If you’re looking at the mountains, go in February. If you’re looking at the desert, go in August. See if you can handle the "boring" parts of the isolation when the weather is miserable.

Take a basic home maintenance course. Learn how to sweat a copper pipe, how to reset a well pump, and how to maintain a chainsaw. These aren't hobbies out there; they are survival skills.

Talk to the local fire department. They are the real experts on the area. Ask them about the "call volume" and what the biggest risks are in that specific zip code. They’ll tell you the truth that the real estate agent won't.

Download offline maps. Before you even go to look at a property, download the entire county on Google Maps. You will lose service, and getting lost on a forest service road with a low fuel light is a rite of passage you want to avoid.