You’re standing on the scale. Maybe you're at the doctor's office, or maybe you're just in your bathroom on a Tuesday morning. The number pops up, and immediately, your brain starts doing math. You want to know if that digit matches your frame, but honestly, the answer is rarely a single, perfect number. Finding a healthy weight for your height is less about hitting a bullseye and more about landing in a broad, sometimes messy territory that accounts for things like your bone density, where you carry your fat, and how much muscle you’ve managed to build over the years.

It’s frustrating.

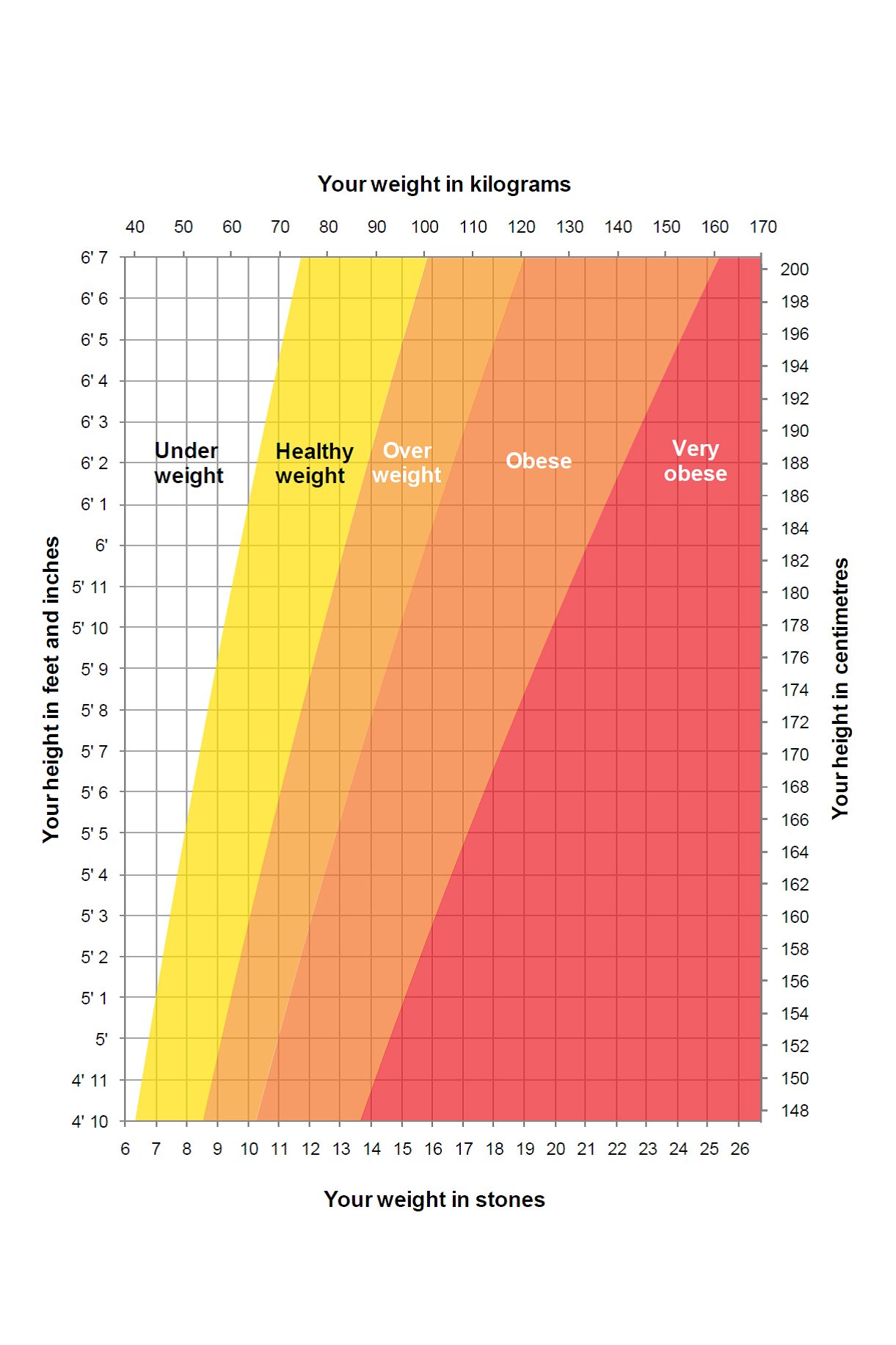

We’ve been conditioned to look at those old-school posters in the nurse’s office. You know the ones. They have height on one side and a "desirable" weight on the other. But bodies don't work in two dimensions. A 5'10" retired athlete who spends four days a week lifting weights is going to have a drastically different "healthy" number than a 5'10" office worker who hasn't broken a sweat since 2019. One might be technically "overweight" by the book, yet metabolically perfect. The other might be "normal" weight but carry dangerous levels of visceral fat around their organs.

The BMI Problem and Why We Still Use It

Let’s talk about the Body Mass Index. It’s the elephant in the room. Developed in the 1830s by a Belgian mathematician named Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet, BMI was never actually meant to diagnose individuals. Quetelet was a statistician, not a physician. He wanted to find the "average man" for social research. Yet, here we are, nearly 200 years later, using his formula—weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared ($BMI = kg/m^2$)—to decide who is healthy.

It's a crude tool.

Basically, BMI can't tell the difference between five pounds of muscle and five pounds of fat. If you're a "outlier"—maybe you're very tall, very short, or very athletic—the BMI is going to lie to you. For instance, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) has published numerous studies suggesting that for some populations, especially older adults, a slightly higher BMI might actually be protective against certain diseases. This is often called the "obesity paradox," though it's really just a testament to the fact that weight is a nuanced indicator of health.

Despite the flaws, doctors use it because it’s fast. It’s a screening tool. It’s a starting point, not the finish line. If your BMI is high, it doesn't automatically mean you're unhealthy; it just means your provider should probably look deeper at your blood pressure, your cholesterol, and your blood sugar.

Beyond the Scale: The Waist-to-Hip Ratio

If you want a better answer for what a healthy weight for your height actually looks like, grab a measuring tape. Honestly, where you store your fat matters way more than how much you weigh in total.

Subcutaneous fat—the stuff you can pinch on your arms or legs—is mostly a cosmetic concern. It’s the visceral fat, the stuff tucked deep inside your abdomen around your liver and intestines, that causes the real trouble. This fat is metabolically active. It pumps out inflammatory cytokines and is linked directly to Type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

This is why health experts like those at the Mayo Clinic often prioritize waist circumference over the scale. For most women, a waist measurement over 35 inches is a red flag. For men, it’s 40 inches. You could be within a "healthy weight" range for your height and still have a waistline that puts you at risk. This is sometimes called "skinny fat" or metabolically obese normal weight (MONW). It sounds like a contradiction, but it's a real medical phenomenon that catches people off guard during routine blood work.

Try calculating your waist-to-hip ratio instead of just staring at the scale. Divide your waist measurement by your hip measurement. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a ratio of 0.90 or less for men and 0.85 or less for women is generally considered healthy. It gives you a much clearer picture of your "shape" and what that shape means for your internal organs.

Muscle Mass: The Great Weight Inflator

Muscle is dense. It’s heavy. It’s also your best friend for longevity.

When people ask about a healthy weight for their height, they often forget that muscle weighs significantly more by volume than fat. If you start a strength training program, you might see the scale go up while your pants get looser. This is the ultimate "healthy weight" victory, but it causes many people to panic because they're obsessed with the number.

A person who is 5'6" and 160 lbs with 20% body fat is in a completely different health category than a person who is 5'6" and 160 lbs with 35% body fat. The first person has a high metabolic rate, better insulin sensitivity, and stronger bones. The second person might struggle with fatigue or joint pain. The scale sees them as identical. Your body doesn't.

Why Bone Density Matters

As we age, our bones can lose density, especially in women post-menopause. This weight loss isn't "good." It’s a sign of frailty. A "healthy weight" for an 80-year-old woman is often higher than what she weighed at 25, and that’s okay. That extra weight provides a literal cushion in case of a fall and a metabolic reserve if she gets sick. We have to stop viewing the lowest possible weight as the healthiest possible weight. It just isn't true across the lifespan.

Ethnicity and Genetic Variance

We also have to acknowledge that the "standard" charts were largely built on data from people of European descent. That’s a massive oversight. Research has shown that people of South Asian descent, for example, tend to have higher risks for heart disease and diabetes at much lower BMI levels than Caucasians. For a person of Asian descent, a "healthy" BMI might actually top out at 23 or 24, rather than the standard 25.

Conversely, some studies suggest that African Americans may have higher bone density and muscle mass, meaning a slightly higher BMI might not carry the same health risks as it would for other groups. Health isn't one-size-fits-all because our DNA isn't one-size-fits-all. You have to look at your personal family history. Does your family have a history of diabetes at lower weights? That matters more than a generic chart.

Metabolic Health vs. Weight

Let's look at the "Metabolically Healthy" markers. If you want to know if your weight is right for your height, check these five boxes:

- Blood Pressure: Is it consistently below 120/80?

- Blood Sugar: Is your fasting glucose under 100 mg/dL?

- Triglycerides: Are they below 150 mg/dL?

- HDL Cholesterol: Is it high enough (above 40 for men, 50 for women)?

- Waist Circumference: Is it within those healthy ranges we talked about?

If you hit all five of those, your current weight—even if it's "overweight" on a chart—is likely working for you. You're metabolically fit. Focusing on these markers instead of the scale prevents the "yo-yo dieting" cycle that actually wreaks havoc on your metabolism.

Every time you crash diet to hit a "healthy" number, you lose muscle. When you inevitably gain the weight back, you gain it back as fat. Over time, your body composition gets worse even if your weight stays the same. It’s a trap.

How to Determine Your Personal Healthy Range

Stop looking for a single number. Think in ranges. A 15-to-20-pound window is a much more realistic goal than trying to stay at exactly 142 pounds.

Start by looking at your history. When did you feel your most energetic? When were your lab results the best? When could you move comfortably without joint pain? That’s your "set point" or your natural healthy weight. It’s the weight your body maintains when you’re eating nutritious food and staying active without being obsessive.

If you’re currently far outside that range, don't aim for the "ideal" height/weight chart number immediately. Aim for a 5% to 10% reduction in your current weight. Medical research consistently shows that losing just 5% of your body weight can drastically improve blood pressure and insulin resistance. You don't have to be "thin" to be significantly healthier.

Actionable Steps for Moving Forward

Forget the "ideal" weight for a moment. Instead of obsessing over the height-weight ratio, focus on these specific, measurable changes that actually influence your health:

1. Measure your waist-to-height ratio. This is a simpler and often more accurate metric than BMI. Aim to keep your waist circumference less than half of your height. If you are 70 inches tall (5'10"), your waist should ideally be under 35 inches. It’s a quick check that tells you more about your risk than a scale ever could.

2. Prioritize protein and resistance training. Since muscle mass is the variable that "breaks" the BMI scale in a good way, focus on building it. This increases your basal metabolic rate, meaning you burn more energy just sitting still. It also ensures that any weight you do lose comes from fat stores, not your functional tissue.

3. Get a DEXA scan or a BodPod test if you're curious. If you really want to know what’s going on, ignore the $20 bathroom scale. These professional tests can tell you exactly how much of your weight is bone, muscle, and fat. It’s eye-opening to realize you might be "overweight" but have the body fat percentage of an athlete.

📖 Related: Juice No Sugar Added: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Morning Glass

4. Track your "Non-Scale Victories" (NSVs). How do your clothes fit? How is your sleep quality? Can you climb two flights of stairs without gasping for air? These are much better indicators that you’re at a healthy weight for your height than a digital readout.

5. Consult a professional who looks at the whole picture. Find a doctor or a registered dietitian who talks about "health at every size" or focuses on metabolic markers rather than just weight loss. If they don't ask about your stress levels, sleep, and activity, they aren't getting the full story.

The truth is, a healthy weight for your height is a moving target. It changes as you age, as you build muscle, and as your lifestyle evolves. Use the charts as a rough guide, but listen to your blood work and your energy levels. They don't lie. Weight is just one data point in the very complex story of your health. Don't let it be the only one you read.