You’re standing in the middle of a literal swamp in the Lowcountry. Moss is dripping off live oaks like grey hair, and the air is so thick with humidity you could practically chew it. Somewhere under a pile of brambles and a century of pine needles is a headstone. Or maybe just a fieldstone. This isn't the clean, manicured experience the movies promise. When you try to find a grave in South Carolina, you aren't just looking for a name on a rock; you’re fighting 300 years of hurricanes, shifting property lines, and a landscape that actively tries to swallow its own history.

Most people start their search online. They go to the big sites, type in a name, and hope for a GPS coordinate. Sometimes it works. Often, it doesn't.

South Carolina's geography is weirdly specific. You have the Upstate with its red clay and rocky outcrops, and then you have the Lowcountry where the water table is so high that older burials had to be creative just to keep the pine boxes from floating away during a storm. If you're serious about this, you have to realize that "the internet" only knows about 60% of what's actually in the dirt here.

Why Digital Records Often Fail You

Digital databases are amazing, but they are maintained by volunteers. In South Carolina, many of our most historic cemeteries are on private land—former plantations that have been subdivided ten times over. A volunteer might have walked that land in 1994, but today, that cemetery is behind a gated community's pool house or buried under a strip mall in Mount Pleasant.

The data is only as good as the last person who took a photo.

Let’s talk about the "Lost" cemeteries. During the mid-20th century, South Carolina underwent massive infrastructure changes. Projects like the Santee Cooper hydroelectric project created Lake Marion and Lake Moultrie. Do you know what’s at the bottom of those lakes? Cemeteries. Thousands of graves were moved, but not all of them. If your ancestor’s record says they were buried in a town that no longer exists, you aren't looking for a headstone anymore; you're looking for a relocation record in a dusty ledger at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia.

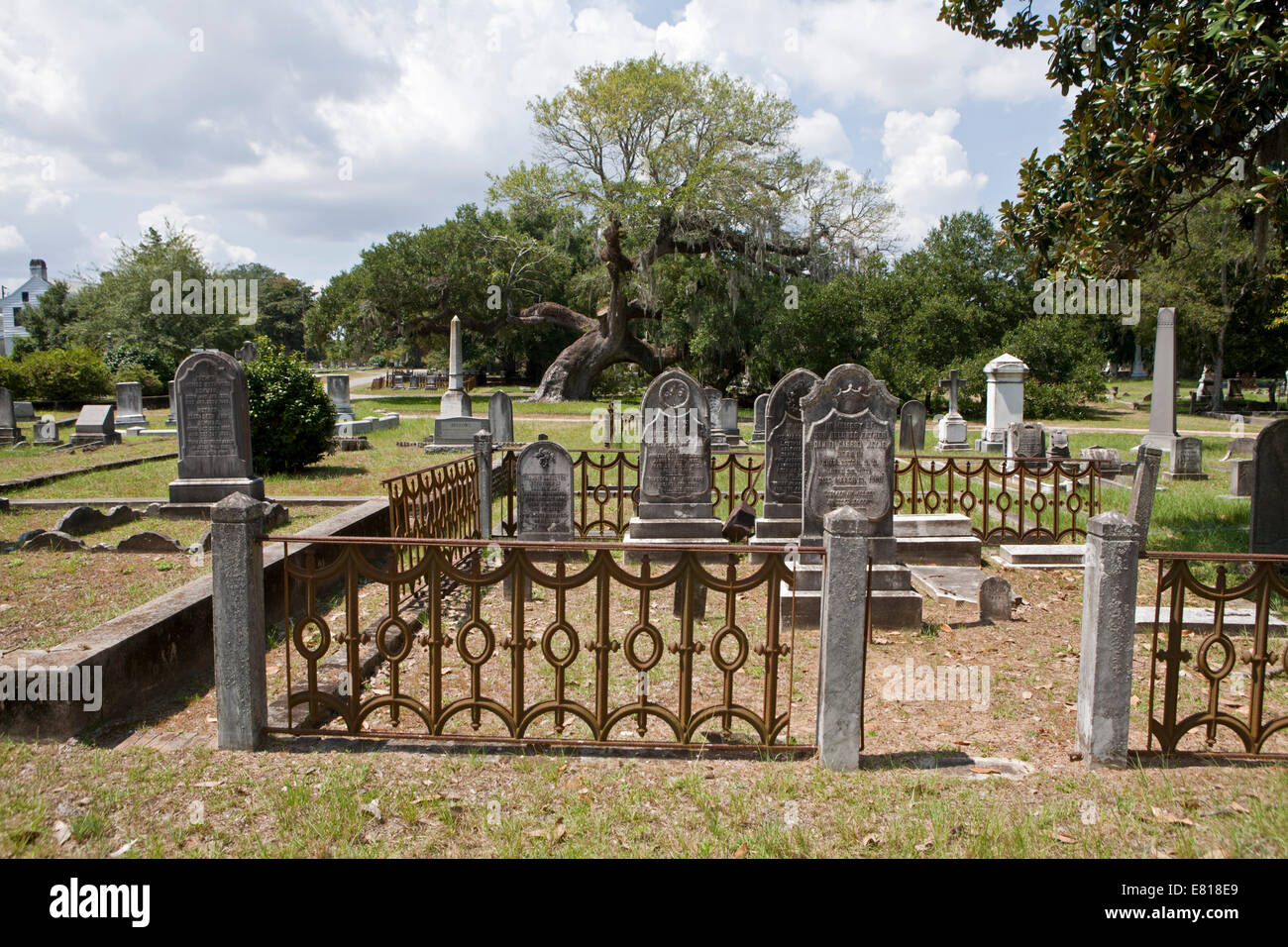

The Reality of the Lowcountry "Burial Ground"

In the coastal regions, you have to account for the Gullah-Geechee traditions. These aren't your typical European-style graveyards with neat rows of granite. Often, these are "spirit houses" or burial grounds marked with personal items—clocks, medicine bottles, or even ceramic shards. To the untrained eye of a modern developer or a casual searcher, these can look like "empty" woods.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

They aren't empty.

If you are trying to find a grave in South Carolina within these coastal communities, searching for a traditional headstone might lead you to a dead end. You have to look for the depressions in the earth. You have to look for the Yucca plants or the Periwinkle. These plants were often used to mark graves because they stay green and survive the heat. Nature is the most honest record-keeper we have left in the South.

Where the Real Data Lives (It’s Not Always Online)

Forget the big national apps for a second. If you’ve hit a brick wall, you need to pivot to the county level. South Carolina has 46 counties, and each one treats its records differently.

The South Carolina Genealogical Society is basically the gold standard here. They have local chapters like the Old Darlington District Chapter or the Chester County Genealogical Society. These folks have the "tombstone inscriptions" books. Back in the 1970s and 80s, long before the internet, local historians walked these woods and transcribed what they saw. These physical books often contain records of stones that have since been stolen, weathered into illegibility, or destroyed by falling trees.

- County Probate Courts: This is where the money is. If a person died with any kind of property, there’s a probate file. These files often list the expenses for the "coffin and burial." Sometimes, the receipt from the local general store or the sexton will tell you exactly which churchyard they went to.

- WPA Records: During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration sent people out to survey cemeteries. These records are housed at the South Caroliniana Library at USC. It’s a gold mine.

- Church Records: Especially in the Upstate, the Baptist and Presbyterian churches kept meticulous records. However, many of these "session minutes" are not digitized. You have to physically go to places like the Presbyterian College archives or the Furman University Special Collections.

Dealing with the "Lost" Confederate and Revolutionary Markers

South Carolina is a battlefield. Period. From the Revolutionary War at Kings Mountain and Cowpens to the Civil War sieges of Charleston, there are thousands of soldiers buried in mass graves or unmarked trenches.

If you're looking for a veteran, the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum can be a resource, but honestly? Check the pension applications. When widows applied for their pensions, they often had to describe the death and burial of their husbands in heartbreaking detail. "He was buried in the orchard behind the old barn" is a common refrain.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Finding that orchard today? That’s the real trick. You’ll need to cross-reference 19th-century "Sanborn Maps" or "Plat Maps" with modern Google Earth. It’s detective work. It’s messy. It’s frustrating.

Practical Steps to Locating a Specific Plot

Don't just drive out to a rural county and start wandering into the woods. That’s a good way to get a face full of golden silk orb-weaver webs or, worse, a trespassing charge.

- Verify the County Lines: South Carolina changed its county boundaries multiple times in the 1800s. Someone "buried in Marion" in 1850 might actually be in what is now Florence County. Always check the "formation dates" of the counties.

- Contact the SC Department of Archives and History: Use their online catalog (Boyle) first. Look for "Cemetery Records" under the specific county name.

- Use the "Find A Grave" Photo Request Feature: If you see a listing but no photo, there are local "cemetery angels" who live for this stuff. They will go out with a weed whacker and a bottle of water just to get you a picture.

- Learn to Read "D/2" Solution: If you do find a stone and it's covered in black lichen, do not use bleach. Do not use a wire brush. You will kill the stone. Use a biological cleaner like D/2 and a soft plastic brush.

The Mystery of the African American Burial Grounds

This is perhaps the most difficult—and most rewarding—part of trying to find a grave in South Carolina. For over a century, the burials of enslaved people and later, sharecroppers, were systematically ignored by official record-keepers. These cemeteries are often located on the "margins"—the edges of fields, the banks of rivers, or the high ground near former quarters.

The African American Cemetery Alliance of SC is doing incredible work here. They are mapping these sites using LiDAR technology, which "sees" through the forest canopy to find the undulations in the ground that signify burials. If your search involves an African American ancestor from the 19th century, your best bet isn't a headstone; it's oral history from the oldest living members of the nearest historic Black church. They usually know where "the old ground" is.

Understanding the Symbols

When you finally do find the stone, look at the carvings. They aren't just decorations.

- A willow tree usually means a long life or "mourning."

- A broken column means a life cut short (often a younger man).

- Hands clasping can mean a husband and wife waiting to meet again, or a welcome into heaven.

- Lambs are almost always children.

In the South Carolina Upstate, you’ll see a lot of "upright" thin slabs made of local slate or soapstone. These are incredibly durable but the "sugar marble" from the Victorian era? That stuff melts like an ice cube in the South Carolina rain. If the stone is blank, it might not have always been that way. Acid rain and humidity are the enemies of memory.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Actionable Next Steps for Your Search

If you’re stuck right now, here is exactly what you should do tomorrow morning.

First, call the public library in the county seat where you think they are buried. Ask for the "South Carolina Room" or the "Local History Room." These librarians are the unsung heroes of genealogy. They often have hand-typed binders filled with cemetery surveys from the 1950s that have never seen a scanner.

Second, check the "Death Certificates" on the SC Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) website. For deaths after 1915, the certificate almost always lists the "Place of Burial." It might just say "Family Cemetery," but that gives you a starting point.

Third, look for the "History of [County Name]" books written in the late 1800s. Authors like Alexander Gregg or J.B.O. Landrum often mentioned prominent families and where their private graveyards were located.

Finding a grave in South Carolina is a marathon, not a sprint. It’s about piecing together land deeds, church minutes, and the physical reality of a landscape that is constantly changing. But when you finally find that weathered piece of stone in the middle of a quiet woods, and the light hits the name just right, the 300 years between you and them just... disappears.

Start with the DHEC death certificate indexes for any ancestor who passed after 1915 to get a confirmed name of a cemetery. For those earlier than 1915, your next move is to locate the "Plat Maps" for the family's land at the County Register of Deeds to see if a small square marked "Cem" or "Grave Lot" appears in the corners of the property.