If you walked into a high-end post-production house in 2005, you’d see a sea of silver towers running Apple’s flagship video software. It was the undisputed king. Then, 2011 happened. Apple dropped Final Cut Pro X, and the industry basically had a collective meltdown because the "Magnetic Timeline" felt less like a professional tool and more like a toy. Fast forward to today, and Final Cut Pro has clawed its way back into the good graces of YouTubers, wedding filmmakers, and even some feature film editors, but the scars from that "X" transition still haven't fully healed for the old guard.

Final Cut Pro is weird. It doesn't work like Premiere Pro. It definitely doesn't work like Avid.

It treats video like a database rather than a physical strip of film. For some, that's a godsend that speeds up their workflow by 50%. For others, it’s a frustrating puzzle that makes them want to throw their MacBook Pro out a window. Honestly, if you're looking at final cut video software as your next big investment, you need to understand that you aren't just buying an app—you’re adopting a completely different philosophy of how digital media should behave.

The Magnetic Timeline: Genius or Gimmick?

Most video editors use a track-based system. You put video on Track 1, audio on Track 2, and if you move something, you have to be careful not to overwrite anything else. Final Cut Pro tosses that out.

The Magnetic Timeline is the heart of the experience. When you move a clip, everything else slides out of the way to make room. It prevents "slugs" or accidental gaps in your edit. It’s fluid. It’s fast. But man, it can be annoying when you're trying to do a complex multi-layered composite and things start shifting around because you bumped a clip by one frame.

Apple calls this "fluid editing."

Critics call it "unpredictable."

The truth is somewhere in the middle. Once you master "Connected Clips" and "Compound Clips," you realize that Final Cut Pro is actually incredibly organized. It’s just that it forces you to organize your footage before you start cutting, rather than during the process. If you’re the type of person who just dumps files onto a timeline and hopes for the best, you’re going to have a bad time.

Keywords and Roles: The Database Approach

What really sets final cut video software apart from its competitors isn't the shiny interface; it's the metadata.

Imagine you’re editing a documentary. You have 40 hours of interview footage. In Premiere, you’d probably make a dozen different "bins" (folders) and try to sort clips by name. In Final Cut, you use Keywords. You can tag a ten-second portion of a clip as "funny," "wide shot," and "John Smith." When you click that keyword in your library, boom—every instance of John Smith being funny in a wide shot appears instantly.

It’s a database.

Then there are "Roles." Instead of manually moving audio clips to specific tracks to keep things organized, you assign a Role to a clip (like "Dialogue," "Music," or "Effects"). When it’s time to export, you tell Final Cut to export a version with only the "Music" and "Effects" roles, and it handles the heavy lifting. No more soloing tracks or muting channels manually. It’s elegant, but it requires a level of discipline that many editors simply aren't used to.

The Silicon Advantage

We have to talk about hardware because Apple owns the whole stack. Since the launch of the M1, M2, and now M3 chips, Final Cut Pro has become a speed demon.

Because Apple writes the software specifically for their own silicon, the optimization is absurd. You can often edit 4K or even 8K ProRes footage on a MacBook Air without it turning into a space heater. While Premiere Pro has made massive strides in stability, it still feels like a guest in the macOS ecosystem. Final Cut Pro lives there. It pays rent. It knows where the spare keys are.

If you’re working with ProRes—Apple’s own high-quality, intermediate codec—the performance is basically untouchable. It’s the difference between a car that’s been tuned for a specific track and a generic SUV trying to navigate the same turns.

The iPad Pro Factor

In a move that surprised nobody and everybody at the same time, Apple finally brought Final Cut Pro to the iPad.

📖 Related: How to Add Photos on TikTok: The Stuff Everyone Forgets to Do

It’s not just a port of the desktop version. They redesigned the interface for touch, adding a "Jog Wheel" that actually feels surprisingly natural for scrubbing through footage. For a generation of creators who grew up on iPhones and iPads, this is their entry point into professional editing.

But there’s a catch.

The iPad version is a subscription model, whereas the Mac version remains a one-time purchase (for now). This has caused a bit of a rift in the community. Professional editors who have owned the Mac version for a decade without paying an extra cent are wary that the desktop app might eventually follow the subscription path. Currently, the two versions can talk to each other, but the workflow isn't perfectly seamless yet. You can move a project from iPad to Mac, but going from Mac back to iPad is a bit like trying to fit a gallon of water into a pint glass.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Pro" Label

There’s this lingering myth that Final Cut Pro isn't for "real" movies.

That’s nonsense.

The Social Network was edited on Final Cut Pro (the older version, but still). Focus, starring Will Smith, was one of the first major Hollywood films to be cut entirely on the "X" version. More recently, plenty of award-winning indies and high-end commercials use it. The reason it isn't the "industry standard" in Hollywood isn't because it’s less capable; it’s because Hollywood is built on Avid-based pipelines that have existed for thirty years. Switching a whole studio's infrastructure to a new software isn't just a software change—it’s a million-dollar logistical nightmare.

For independent creators, small agencies, and social media professionals, Final Cut is arguably the most efficient tool on the market. It’s built for speed.

👉 See also: 13 Divided by 14: What Most People Get Wrong About This Repeating Decimal

The Ecosystem of Plugins

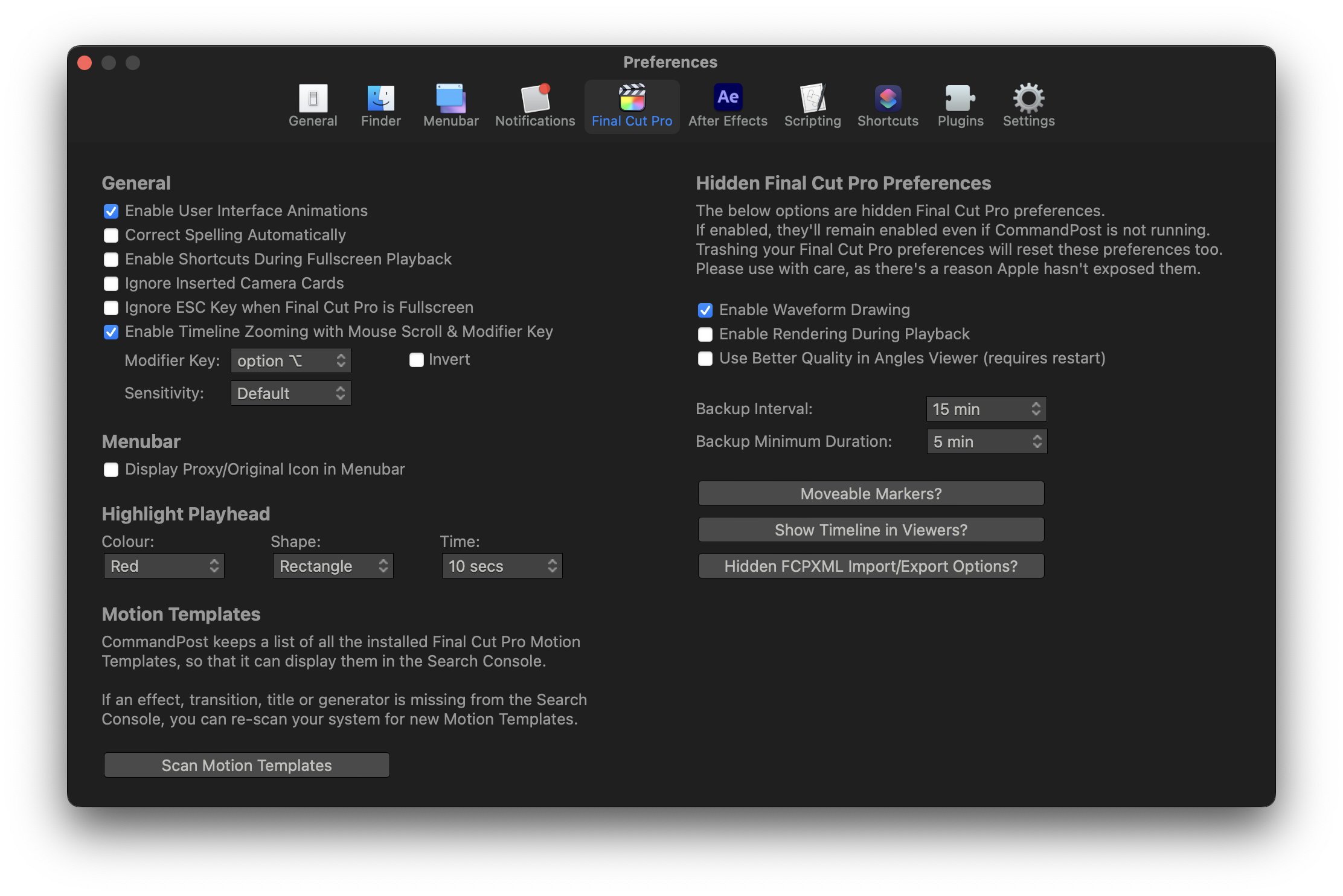

Because Apple keeps the core interface of Final Cut Pro relatively clean (some say sparse), a massive secondary market of plugins has emerged.

Companies like MotionVFX and Coremelt have built businesses around making Final Cut do things it can’t do out of the box. Want 3D tracked text? Buy a plugin. Want advanced color grading that feels like DaVinci Resolve? Get Color Finale.

This is both a blessing and a curse. It means you can customize the software to your specific needs. It also means you might end up spending another $300 on top of the base price just to get the functionality you'd expect from a professional suite. However, for most people, the built-in tools for stabilization, basic color correction, and audio cleanup are more than enough.

Making the Choice: Is It Actually For You?

If you are a Windows user, the conversation ends here. Final Cut is Mac-only and always will be.

If you are on a Mac, the decision usually comes down to Final Cut Pro vs. Premiere Pro vs. DaVinci Resolve.

Premiere is great if you need to jump between After Effects and Photoshop constantly. Resolve is the undisputed king of color grading and is actually free for the basic version. Final Cut is for the editor who wants to stay "in the flow." It’s for the person who hates the "clunky" feeling of traditional tracks and wants the computer to do the tedious organization for them.

It’s also worth noting the price. $299 sounds like a lot, but when you compare it to the monthly "Creative Cloud tax" that Adobe charges, Final Cut pays for itself in less than a year. I know people who bought it in 2011 and have received every single update for free for over a decade. In the world of modern software, that is practically unheard of.

The Logic of Motion and Compressor

When you buy Final Cut, you’re often looking at its siblings: Motion and Compressor.

Motion is Apple's answer to After Effects. It’s way faster but lacks some of the deep compositing power. Compressor is a dedicated encoding tool. You don't strictly need them, but if you're doing professional work, they're basically mandatory. They’re each about $50, making the total "Pro Suite" around $400. Still a bargain in the long run.

Final Cut Pro Actionable Insights

If you're ready to jump in, don't just start clicking. You'll get frustrated.

✨ Don't miss: The Country Code for USA: Why Everyone Still Gets It Mixed Up

- Learn the Shortcuts: Final Cut is built for keyboard ninjas. "Command + B" to blade, "V" to disable clips, and "Option + [" to trim. If you aren't using your left hand on the keyboard, you're doing it wrong.

- Trust the Metadata: Spend the first hour of your project tagging your footage. It feels like a chore, but when you're three days into an edit and need to find "that one shot of the dog," you'll thank yourself.

- Proxy Workflows: Even though Final Cut is fast, if you're working with 8K RAW footage, use the "Proxy" feature. It creates small, easy-to-edit files that you can swap back to the originals with one click before you export.

- Back Up Your Libraries: Final Cut saves constantly (there is no "Save" button, which is terrifying at first), but it creates massive library files. Get a fast external SSD—something like a Samsung T7 or a SanDisk Extreme—and run your projects off that. Don't clog up your internal drive.

- Check the Trial: Apple offers a 90-day free trial. That is three months. Use it. Edit a full project from start to finish before you drop the $300. You'll know within the first week if your brain "clicks" with the Magnetic Timeline or if it rejects it like a bad organ transplant.

Final Cut Pro remains a masterpiece of software engineering that is occasionally held back by its own desire to be "different." It’s polished, it’s remarkably stable, and it’s arguably the fastest way to get a story from your head onto a screen. Just be prepared to unlearn everything you think you know about how a timeline is supposed to behave.