Charles Chiniquy was once a superstar. Honestly, there isn’t a better word for it. In the mid-1800s, he was the "Apostle of Temperance" in Canada, a man who could move crowds to tears and convince thousands to pour their whiskey into the gutters. But if you’ve heard his name recently, it’s almost certainly because of his massive, controversial memoir. Fifty Years in the Church of Rome isn't just a book; it’s a time capsule of religious fire, personal scandal, and one of the most dramatic breakups in ecclesiastical history.

People still argue about it. Some view it as a courageous whistleblower's account of corruption, while others see it as a bitter, hyperbolic attack by a man who couldn't handle authority. It’s messy.

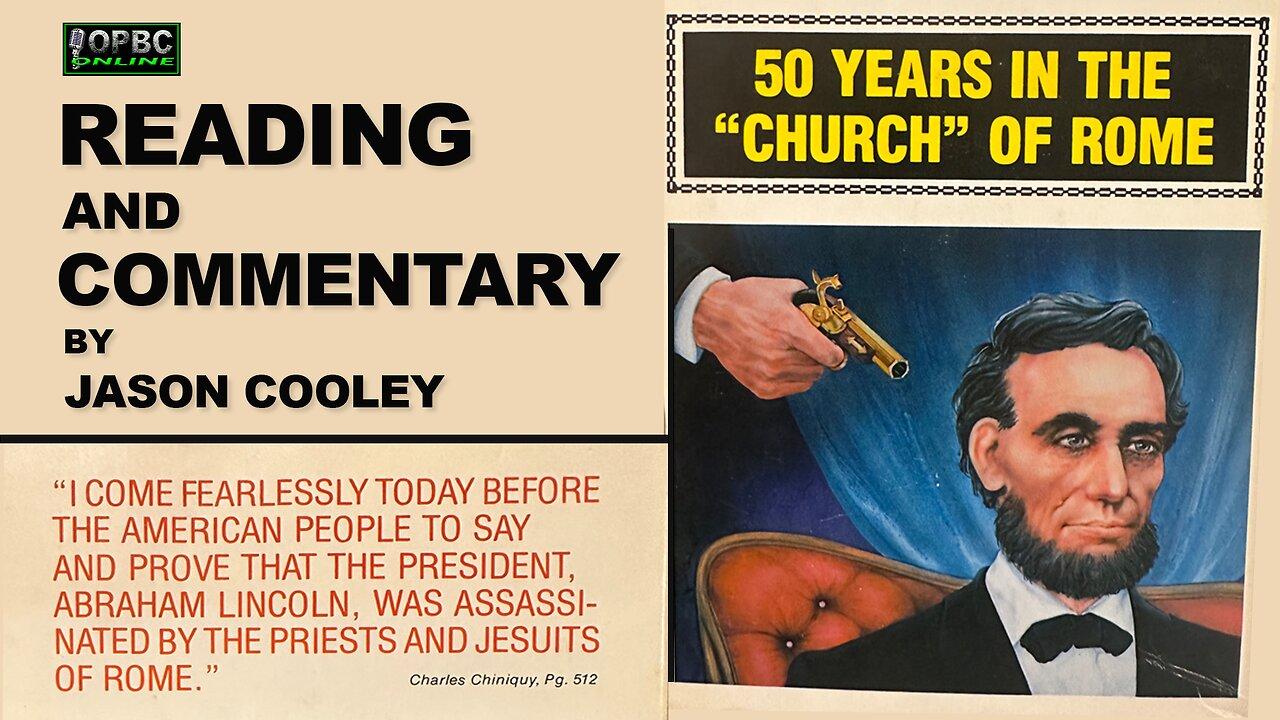

Why Fifty Years in the Church of Rome Still Stirs the Pot

You’ve got to understand the climate Chiniquy was writing in. This wasn't the era of polite interfaith dialogue. It was a time of "No Popery" riots and deep-seated suspicion. When Chiniquy published his account in 1885, he wasn't just writing a diary. He was throwing a grenade into the middle of the North American religious landscape. The book covers his birth in Quebec in 1809 all the way through his high-profile departure from the Catholic Church in the 1850s.

The narrative focuses heavily on the "confessional." Chiniquy argues that the practice of private confession was a tool of psychological control. He goes into excruciating—and often scandalous—detail about how he believed the system was abused. For modern readers, it's a lot to take in. You have to filter it through the lens of a man who had become a Presbyterian minister by the time he sat down to write. He had a specific perspective to prove.

The Abraham Lincoln Connection

Here is a fact that usually catches people off guard: Charles Chiniquy was a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. No, seriously. Before Lincoln was the "Great Emancipator," he was a trial lawyer in Illinois. In 1855 and 1856, Chiniquy found himself entangled in a nasty legal battle with a prominent Catholic layman named Peter Spink. The case was basically about slander and property, but it felt like a trial for Chiniquy's entire reputation.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Chiniquy hired Lincoln.

Lincoln won the case for him. In Fifty Years in the Church of Rome, Chiniquy claims that during this time, he warned Lincoln that the Jesuits were plotting against him. This is where things get complicated for historians. While the legal relationship between the two men is a matter of public record, many of the specific conversations Chiniquy recounts—especially those regarding "Popish plots" to assassinate the President—are viewed with heavy skepticism by modern Lincoln scholars. Chiniquy was writing decades after the assassination. Memories tend to get "sharper" or more dramatic when you’re trying to sell a narrative of cosmic struggle.

The Core Arguments and the Drama of St. Anne

The middle of the book centers on a colony in St. Anne, Illinois. Chiniquy had moved a bunch of French-Canadian immigrants there, essentially creating a private fiefdom. He bumped heads with the Bishop of Chicago, Anthony O’Regan. It was a classic power struggle. Chiniquy portrays himself as the defender of his people's rights, while the Church hierarchy saw him as a rebellious priest who refused to obey his superiors.

It eventually led to his excommunication. Or, as Chiniquy put it, his "liberation."

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

He basically walked out with his entire congregation. It’s a wild scene to imagine—hundreds of families switching denominations overnight because of one man's charisma. In the book, he frames this as a theological awakening sparked by reading the Bible for himself. But if you look at the court records and the letters from the Diocese at the time, you see a much more bureaucratic, messy fight over land titles and administrative authority. It’s rarely just about theology.

Navigating the Controversy: Is it Accurate?

If you’re reading Fifty Years in the Church of Rome for a neutral history, you’re going to be disappointed. It’s an autobiography written by a man who felt wronged. He uses strong, often inflammatory language. He attributes motives to his enemies that he couldn't possibly have known for sure.

- The Tone: It's Victorian. It's high-octane. It's meant to provoke.

- The Facts: The dates and major events (like the trials and the temperance crusades) are generally accurate.

- The Interpretation: This is where the salt shaker comes in. His claims about secret Vatican directives or the "true" nature of every priest he met are his subjective experiences—or his later reflections colored by his new faith.

Scholars like Richard Lougheed have spent years deconstructing Chiniquy’s life. They find a man who was genuinely talented but deeply flawed. He had a massive ego. He struggled with discipline. But he also had a genuine heart for the poor immigrants he led into the American Midwest.

The Legacy of a Polarizing Text

Why do people still download this on Kindle or buy tattered paperback copies? Because it taps into the fundamental human fascination with "insider" secrets. People love a "leaving the cult" or "behind the scenes" story. For many Protestants in the late 19th century, this book was a primary source of information (or misinformation) about how the Catholic Church functioned.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Even today, it’s a staple in certain fundamentalist circles. It's also a fascinating study for psychologists interested in the "convert's zeal"—that specific energy people have when they turn against a system they once loved.

Actionable Takeaways for the Curious Reader

If you're going to dive into this 800-page behemoth, don't just take it at face value. You've got to be a bit of a detective.

- Cross-Reference the Lincoln Years: Read David Herbert Donald’s biography of Lincoln or look into the records of the Illinois courts. It provides a necessary grounding for Chiniquy’s more "out there" claims.

- Understand the Genre: This belongs to the "Ex-Priest" literary genre, which was huge in the 1800s. It has its own tropes and expected beats. Recognize them so you don't get swept away by the rhetoric.

- Look for the Humanity: Beneath the polemics, there is a story about the immigrant experience in America. It’s about people trying to find a home and a faith that made sense in a new, harsh world.

- Check the Sources: When Chiniquy quotes "official documents," realize he is often translating them from memory or using them out of context to bolster his argument.

Fifty Years in the Church of Rome remains a significant, if deeply biased, piece of religious Americana. It shows us how quickly disagreements over policy can turn into full-blown spiritual warfare. It reminds us that history is usually written by the person who holds the loudest megaphone. Whether you see Chiniquy as a hero or a charlatan, his book is a masterclass in how to tell a story that people will still be talking about 140 years later.