So, you’ve finally bagged your first cottontail or jackrabbit. You’re standing there in the brush, heart still thumping a bit, looking down at your harvest. Now what? Honestly, how you handle the next ten minutes determines whether you’re eating a gourmet wild-game dinner or a tough, gamey mess that even the dog might sniff at twice. Learning how to field dress a rabbit is the bridge between hunting and eating. It’s messy. It’s visceral. But it is the most important skill in any small game hunter’s toolkit.

If you leave the innards in too long, the meat spoils. Heat is your enemy. Bacteria in the gut don’t care about your hike back to the truck; they start working immediately.

I’ve seen guys carry whole rabbits around in a game vest for four hours in fifty-degree weather. That’s a mistake. You’re basically sous-viding the intestines inside the carcass. Gross, right? Getting the "guts out" fast isn't just about tradition; it’s about food safety and flavor. You want that meat to cool down as fast as humanly possible.

The Gear You Actually Need (and the Stuff You Don’t)

Don’t buy into the hype that you need a massive bowie knife or some specialized "gut hook" monstrosity. Rabbits are delicate. Their skin is paper-thin. If you go at it with a giant blade, you’re going to puncture the bladder or the stomach, and then you’ve got a real problem on your hands.

A small, sharp folding knife or a fixed-blade paring knife is basically perfect. I personally use a Havalon with replaceable blades because I’m lazy about sharpening, but a classic Buck 110 or even a sharp Swiss Army knife works wonders.

- Gloves: Use them. Seriously. Tularemia (rabbit fever) is a real thing. It’s rare, but it’s nasty enough that a pair of nitrile gloves is worth the ten cents they cost.

- Water: If you have a bottle to rinse your hands, great.

- A Bag: Gallon-sized Ziplocs are the gold standard for keeping the carcass clean on the way home.

The Two-Minute Method: How to Field Dress a Rabbit

There are a dozen ways to do this, but when you’re out in the field, simplicity wins. We aren’t doing a full butchery job here; we are just removing the heat source (the guts).

First, lay the rabbit on its back. Some hunters prefer to hang them by the back legs, but if you’re in the middle of a field with no trees, the ground is your table. Pin the rabbit down and find the sternum—that's the chest bone.

You’re going to make a small incision right below the ribcage. Be careful. Just nick the skin and the thin muscle layer. Don't go deep. If you see green or smell something like a wet hayloft, you went too deep and hit the stomach.

💡 You might also like: Tritan Plastic Wine Glasses: What You’re Probably Getting Wrong About Unbreakable Stemware

Once you have a small opening, insert two fingers (index and middle) into the hole, pointing toward the tail. Use your fingers to lift the wall of the abdomen away from the internal organs. Run your knife down between your fingers all the way to the pelvis. This "zipper" move keeps the blade from poking the guts.

Dealing with the "Core"

Now comes the part that makes beginners squeamish. You have to reach in and pull. Reach up into the chest cavity—you might have to snip the diaphragm, which is that thin membrane separating the lungs from the stomach—and grab the windpipe. Pull downward toward the tail.

The heart, lungs, stomach, and intestines should all come out in one relatively neat package. If the bladder is still attached near the back legs, be extra careful removing it so you don't leak urine on the hind quarters.

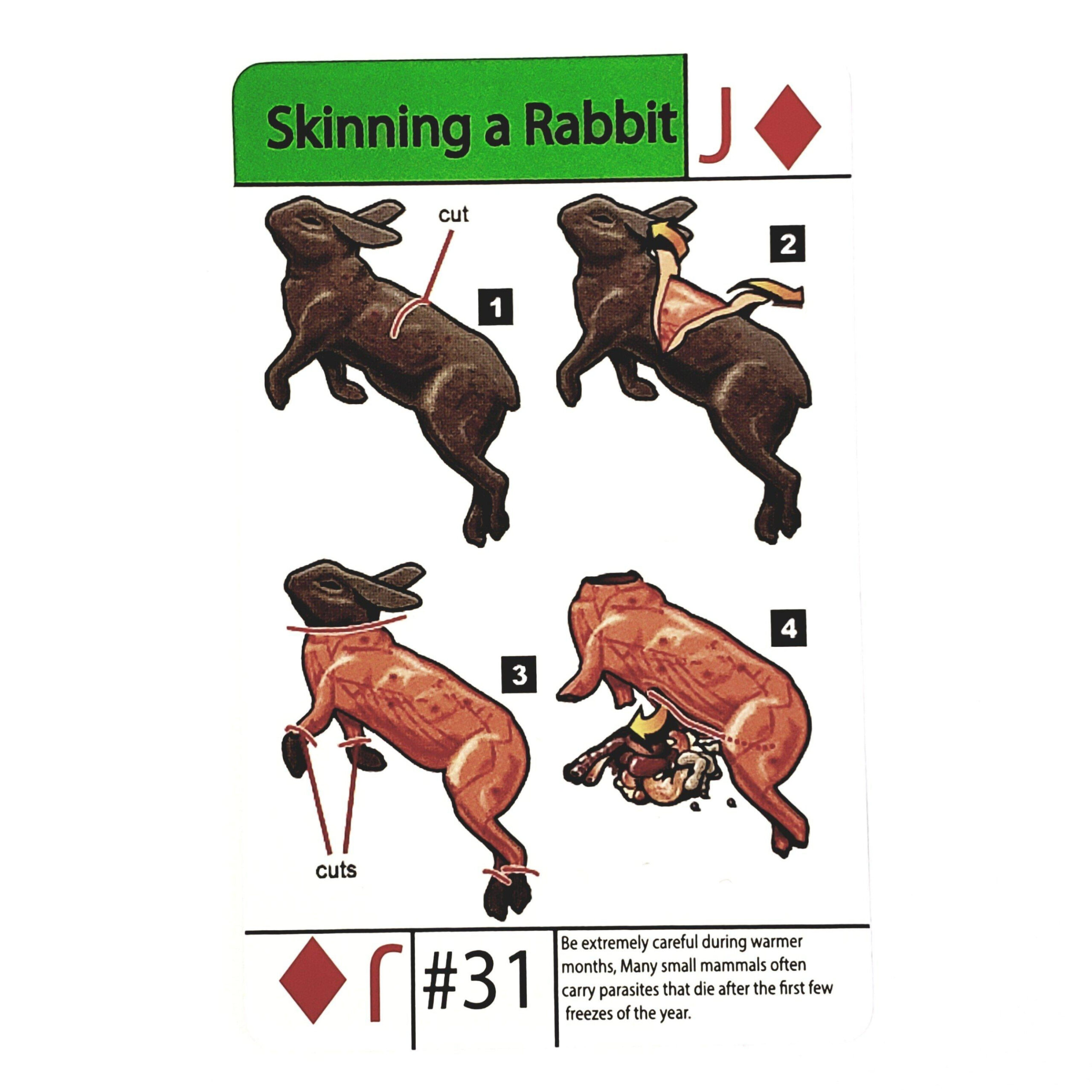

What About the Skin?

Some people like to skin them immediately. I usually wait until I’m back at a tailgate or a kitchen sink unless it’s unusually hot. Leaving the skin on keeps the meat clean from dirt and hair while you’re hiking. Rabbit hair is notorious. It’s like static-charged lint; once it touches the meat, it’s a nightmare to get off.

If you do choose to skin it now, use the "sweater" method. Pinch the skin on the back, cut a slit across the spine, put your fingers in, and pull in opposite directions. The skin will slide off the front and back like a pair of socks. It’s surprisingly easy—sometimes too easy, and you’ll realize how fragile they are.

👉 See also: Why The Pioneer Woman Mercantile Menu is Actually Worth the Drive to Pawhuska

The Tularemia Check: Don't Skip This

Expert hunters like Steven Rinella and various state wildlife agencies always emphasize checking the liver. This is non-negotiable. Before you toss the remains, look at the liver. It should be a deep, consistent dark red or purple.

If you see tiny white spots—think grains of salt or small white freckles—drop the rabbit. Do not eat it. Do not feed it to your dog. Bury it or leave it for the coyotes and wash your hands/knife thoroughly. Those spots are a primary indicator of Tularemia. It’s a bacterial disease that can jump to humans through cuts in the skin or by eating undercooked meat. It’s rare, but it’s the reason we wear gloves.

Understanding the "Squeeze" Technique

There is an old-school woodsman trick for how to field dress a rabbit without even using a knife. It’s called the "squeeze" or "centrifugal force" method. You basically hold the rabbit by the front legs and "whip" it toward the ground or squeeze the ribcage down toward the tail to force the entrails out of a small tear or the rear orifice.

Honestly? It’s effective if you’re in a massive hurry, but it’s messy. It often ruptures the internal organs, which taints the meat. If you care about the quality of your dinner, stick to the knife. It’s cleaner, more surgical, and ensures you aren't eating ruptured gallbladders.

Temperature Control and Transport

Once the rabbit is empty, wipe out any excess blood. If you have a clean cloth, use it. If not, some clean dry grass can work in a pinch, but be careful not to introduce more debris.

📖 Related: Thinking of Wood Gardens Apartments in Hoover? Here is What the Reviews Don’t Tell You

Don't toss the warm rabbit into a plastic bag and seal it immediately if you can avoid it. That traps the heat. If you have a mesh game bag or even just a loose pocket in your vest, let the air circulate for a bit. The goal is to get that carcass temp down below 40 degrees as fast as you can once you get back to the cooler.

Why Small Game Processing Matters for Conservation

Hunting isn't just about the shot. It’s about the full cycle. When you process a rabbit correctly, you’re showing respect for the animal. Waste is the biggest sin in hunting.

According to various hunter-education programs, nearly 30% of wild game meat is lost due to poor field dressing and handling. That’s a staggering number. By learning the right way to open the cavity and cool the meat, you ensure that the animal's life translates into high-quality protein for your family.

Common Misconceptions About Wild Rabbit

People think wild rabbit tastes like chicken. It doesn't. Not really. It’s much leaner, and the flavor is dictated by what they eat. A rabbit from a desert environment will taste different than one from a clover-heavy meadow in the Midwest.

Also, people worry about "worms." You might find small cysts or tapeworm larvae in the abdominal cavity or attached to the liver. While it looks gross, it usually doesn't affect the meat. Just remove them and cook the meat to an internal temperature of 160°F. Most parasites in rabbits are species-specific and won't harm humans if the meat is handled and cooked properly—but always check that liver for the white spots mentioned earlier. That's the real red flag.

Actionable Next Steps for the Successful Hunter

Once you’ve finished the initial field dressing and you're back at your home base, follow these steps to finish the job:

- Final Skinning: If you haven't already, strip the hide. Cut off the feet at the "wrists" and "ankles" using heavy kitchen shears or your knife.

- The Brine Soak: This is the "secret sauce." Put your cleaned rabbit pieces in a bowl of cold water with a heavy handful of salt. Let it sit in the fridge for 4-12 hours. This draws out the remaining blood and "mellows" the gamey flavor.

- Quartering: Don't cook the rabbit whole unless you're roasting it on a spit. Break it down into the four legs (the front legs are small, the back legs are the prize) and the saddle (the back).

- Silver Skin Removal: Use a sharp fillet knife to remove as much of the silver skin (the shiny, tough membrane) as possible. It doesn't break down during cooking and makes the meat feel tough.

- Slow Cooking: Wild rabbits are athletes. They are tough. Unless you have a very young "fryer" rabbit, braising them in liquid (wine, stock, or even cream) for 2-3 hours is the best way to ensure the meat falls off the bone.

Getting the process right in the field is the difference between a "one-and-done" hunting experiment and a lifelong passion for foraging your own food. Keep your knife sharp, watch the liver, and get those guts out fast. Your taste buds will thank you later.