You’ve heard the story. A lone genius sits in a workshop, sparks fly, and suddenly the world changes forever. Most of the time, that genius is portrayed as a guy in a lab coat. Honestly, that’s a load of garbage. For centuries, female inventors and their inventions were sidelined, buried in patent filings under their husbands' names, or just flat-out ignored by history books that preferred a simpler narrative.

It’s not just about "representation." It’s about credit.

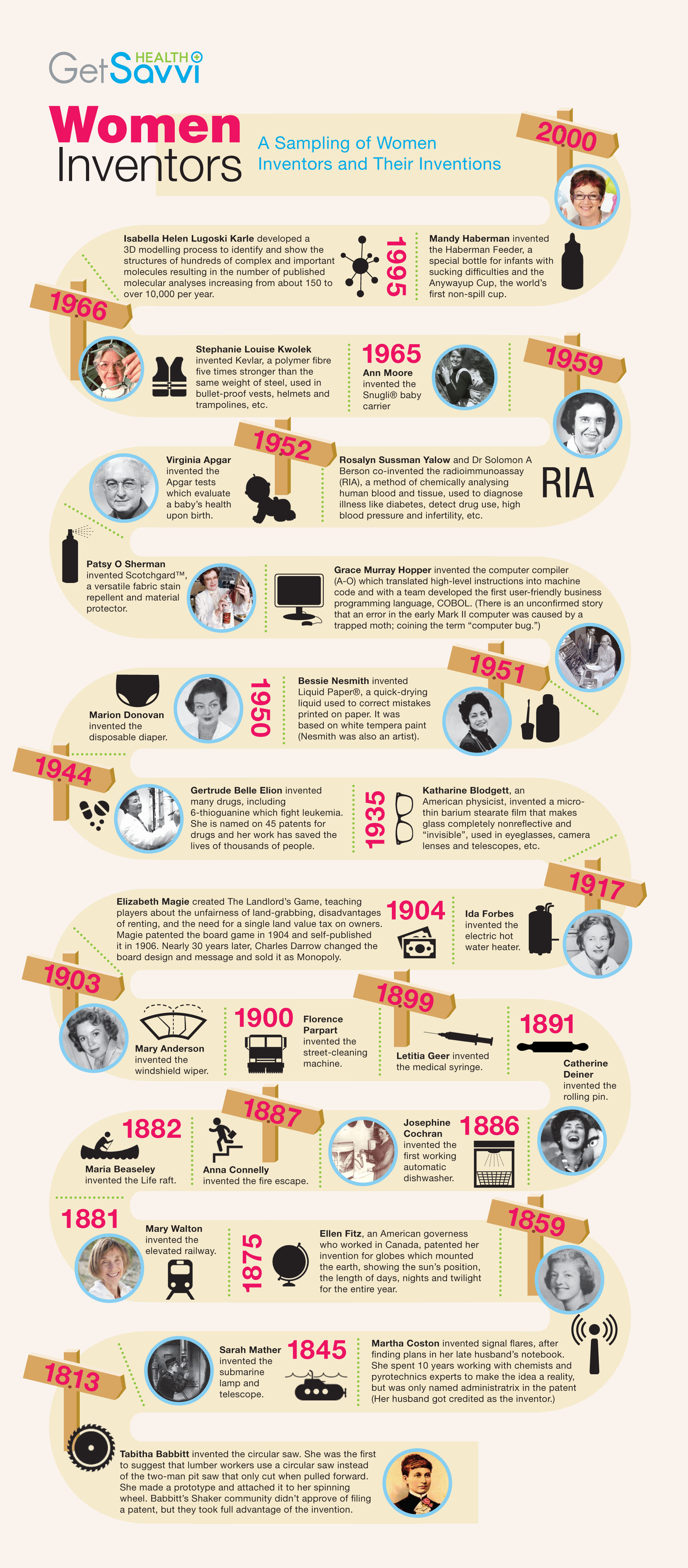

If you’re using Wi-Fi to read this, or if you’ve ever survived a rainy drive because of windshield wipers, you’re living in a world built by women. But here’s the thing: many of these breakthroughs didn't happen in high-tech labs. They happened out of sheer, localized frustration. Take Mary Anderson. In 1902, she was riding a streetcar in a snowy New York City. She watched the driver get out repeatedly to wipe the sleet off the glass. It was dangerous. It was annoying. While everyone else just accepted the cold, Anderson sketched a swinging arm with a rubber blade.

She got the patent. Then, the car companies told her the invention had "no commercial value." A few years later, Cadillac made them standard. She didn't get a dime.

Why We Keep Forgetting About Female Inventors and Their Inventions

The "erasure" isn't always a conspiracy; sometimes it's just how the patent system was rigged. In the early 1800s, US law basically said a married woman’s property—including her intellectual property—belonged to her husband.

Think about Sybilla Masters. Back in 1715, she figured out a way to clean and refine Indian corn using a series of heavy hammers. It was a massive leap forward for agriculture. But the patent? It was issued to her husband, Thomas, because the British authorities wouldn't put a woman's name on the document. This happened constantly. We will likely never know the true number of female inventors and their inventions because their identities are trapped behind their husbands' initials.

It’s kind of wild when you think about the scale of the loss.

Then you have the "collaboration" issue. Take the ENIAC, the first general-purpose electronic computer. For decades, the guys who built the hardware—Mauchly and Eckert—got all the glory. But the six women who actually figured out how to program the thing? Kathleen McNulty, Frances Bilas, Betty Jean Jennings, Ruth Lichterman, Elizabeth Gardner, and Marlyn Wescoff. They were treated like "refrigerator ladies"—models posing in front of the machine. In reality, they were the first software engineers. They were doing complex differential equations by hand to make the machine work.

🔗 Read more: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

The Frequency Hopping Mystery: Hedy Lamarr

If you want to talk about "hidden in plain sight," you have to talk about Hedy Lamarr. People knew her as a Hollywood siren. "The most beautiful woman in the world," they called her. Nobody cared that she hated the party scene and spent her nights at an inventing table.

During WWII, she realized that radio-controlled torpedoes were too easy to jam. If you could make the signal "hop" between frequencies, the enemy couldn't stop it. She teamed up with an avant-garde composer named George Antheil. They used a player piano mechanism to synchronize the frequency changes.

The Navy took the patent and filed it away.

They told her she should go sell war bonds instead. It wasn't until decades later, when the technology became the backbone of Bluetooth, GPS, and Wi-Fi, that she finally got some recognition. She was a genius living in a world that only wanted her to be a face.

The Tech That Actually Matters

Let’s move past the 1940s. The impact of female inventors and their inventions didn't stop once women could finally hold their own patents. In the 1960s and 70s, we see a massive shift toward materials science and telecommunications.

Stephanie Kwolek is the name you need to know here. She was a chemist at DuPont. In 1965, she was trying to find a fiber that could reinforce tires to make them more fuel-efficient. She ended up with a weird, cloudy liquid that looked like "discarded dishwater." Usually, chemists would throw that out. Kwolek didn't. She persuaded the technician to spin it.

The result was Kevlar.

💡 You might also like: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

Five times stronger than steel, pound for pound. It has saved countless lives in the form of bulletproof vests, but it’s also in suspension bridges, spacecraft, and fiber-optic cables.

- The Circular Saw: Tabitha Babbitt (1813). She saw men struggling with a two-man pit saw and realized a circular blade would be way more efficient.

- The Dishwasher: Josephine Cochrane (1886). She was a socialite who got tired of her servants chipping her fine china. "If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself," she reportedly said. She did.

- The Life Raft: Maria Beasley (1882). She didn't just want a boat; she wanted a fireproof, compact raft with guardrails.

Life-Saving Breakthroughs in Health and Safety

It’s not just "gizmos." A huge chunk of modern medicine rests on the shoulders of women who weren't always welcome in the lab.

Dr. Gladys West. Ever use Google Maps? You’re using her brain. She’s the mathematician whose work on satellite geodesy—basically modeling the Earth’s shape—provided the calculations necessary for the Global Positioning System (GPS). For years, she was just another "hidden figure" at the Naval Surface Warfare Center.

And then there's Alice Parker. In 1919, she patented a central heating system using natural gas. Before her, you were basically hauling coal or wood into every room. Her design wasn't exactly what we use today, but it was the first time someone moved away from localized fireplaces toward a system that could heat an entire building safely.

The Modern Frontier: CRISPR and Beyond

We’re seeing a change now, but it’s slow. Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for CRISPR-Cas9. This is basically a pair of molecular scissors that can edit DNA. It’s arguably the most important scientific discovery of the 21st century.

But even here, there was a massive legal battle over patents.

The fight over CRISPR shows that even when women are at the top of their field, the struggle for ownership of their inventions is still intense. The business of "who owns the idea" is often more cutthroat than the science itself.

📖 Related: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

Why This Matters for Business Today

If you’re an entrepreneur or a tech enthusiast, you have to realize that the most disruptive ideas often come from people who are looking at a problem from the outside.

Women have historically been "outsiders" in engineering. That forced them to solve problems differently. When you look at the history of female inventors and their inventions, you see a pattern of practical, high-impact solutions to everyday crises.

- Observation over Theory: Most of these inventions came from watching how things failed in the real world (windshield wipers, dishwashers).

- Resourcefulness: Using what’s available (player piano parts for torpedo guidance).

- Persistence: Kwolek had to beg her colleagues to test her "cloudy" solution.

What People Get Wrong About the "First" Inventions

There’s a lot of misinformation out there. You’ll see TikToks or articles claiming a woman invented the "first car" or "first computer." That’s usually an oversimplification. Bertha Benz didn't invent the car, but she did take the first long-distance road trip in 1888, acting as a field engineer to prove her husband's invention actually worked. She invented brake linings during that trip when she asked a local shoemaker to nail leather onto the brake blocks.

Ada Lovelace didn't build the hardware for the Analytical Engine, but she wrote the first algorithm intended to be processed by a machine. She saw that computers could do more than just crunch numbers—they could create music or art.

We need to be careful with the facts. We don't need to exaggerate their contributions to make them impressive. The reality is already incredible.

How to Support Modern Inventors

The gap is still real. According to the USPTO, only about 13% of all patent inventors are women. That's a massive amount of untapped potential. If we want the next Kevlar or the next Wi-Fi, we have to change how we fund and support creators.

- Look for the "Internal" Patent: Many companies have internal patent programs. Ensure these are accessible and that women in R&D are being encouraged to file.

- Mentorship over Networking: Networking is fine, but mentorship involves actual skin in the game—helping someone navigate the complex (and expensive) world of patent law.

- Check the History: Before citing a "founding father" of a technology, do a quick search for the women who worked in the lab. Their names are usually there, just in smaller print.

The story of innovation isn't a solo act. It’s a messy, collaborative, and often unfair process. But by recognizing the actual origins of the tools we use every day, we get a much clearer picture of where the next big thing is going to come from. It probably won't come from a boardroom. It’ll come from someone looking at a frustrating problem and saying, "I can fix that."

To truly understand the impact of these creators, start by looking at the patents filed in niche fields like materials science and sustainable energy. Many of the most important patents today are being filed by women-led research teams in universities. Tracking these filings is the best way to see the future before it hits the mainstream market. If you want to dive deeper, the National Inventors Hall of Fame and the USPTO's "Progress and Potential" reports offer the most accurate, data-driven look at how the landscape is shifting.

Stop looking for the lone genius. Start looking for the person who’s tired of things not working. That’s where the real inventing happens.