You’ve seen them. Those stiff, black-and-white grids pinned to the wall of a dusty doctor’s office or buried in the back of a 1990s fitness magazine. They tell you that if you’re five-foot-four, you "should" weigh exactly 114 to 150 pounds. It’s a nice, neat little box. But bodies aren't neat.

Let's be real. Most women looking at a female height weight chart are trying to figure out if they’re "normal." We want a number. We want a stamp of approval that says we’re doing okay. But the history of these charts is surprisingly messy, and honestly, they often ignore the most important parts of being a healthy human being.

Where did the female height weight chart even come from?

It wasn't doctors who invented these. It was insurance companies. Specifically, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (MetLife) started the craze back in the 1940s. They weren't looking at "wellness" in the way we think of it now; they were looking at mortality rates. They wanted to know which policyholders were likely to live the longest so they could calculate premiums.

By 1959, the "MetLife tables" became the industry standard. They categorized women into "small," "medium," and "large" frames. It was revolutionary for the time, but it was also incredibly narrow. They were mostly looking at a specific demographic of insured, middle-class individuals. If you didn't fit that mold—or if you had a lot of muscle, or different bone density, or a different ethnic background—the chart didn't really know what to do with you.

We still see the ghosts of these tables today.

Most modern versions are just a simplified way to look at Body Mass Index (BMI). BMI is just a math equation: your weight in kilograms divided by your height in meters squared. ($BMI = kg/m^2$). It’s a 200-year-old formula created by a mathematician, Adolphe Quetelet, who explicitly said it wasn't meant to measure individual health. Yet, here we are, still using it as a primary diagnostic tool.

The problem with "average"

If you're 5'6" and the chart says you should be 130 pounds, but you spend four days a week lifting weights, that chart is going to lie to you. Muscle is much denser than fat. You might be a "healthy" weight according to your jeans size and your blood pressure, but the scale might put you in the "overweight" category.

It's frustrating.

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

And it's not just about muscle. Bone density varies wildly. A woman with a larger skeletal frame naturally weighs more than someone with a "petite" frame, even if they have the exact same body fat percentage. The standard female height weight chart usually fails to account for this nuance.

A realistic look at the numbers

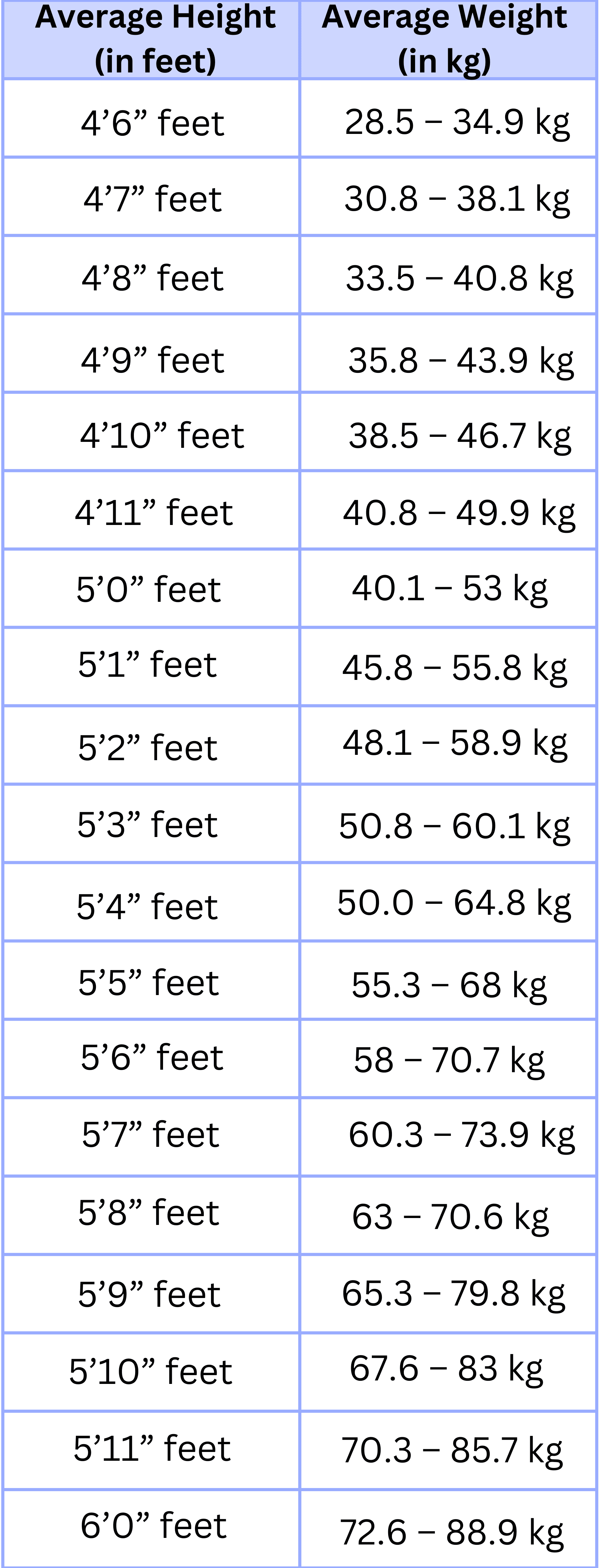

If we look at the CDC guidelines and the standard BMI-based charts used in 2026, the ranges look something like this. Remember, these are broad strokes.

For a woman who is 5'2" (157 cm), the "healthy" range is typically listed between 101 and 135 pounds. Once you hit 5'5" (165 cm), that range shifts to roughly 114 to 150 pounds. By the time you get to 5'9" (175 cm), the "ideal" weight is often cited as 128 to 168 pounds.

But look at those gaps.

A 40-pound range is huge. That’s because health isn't a single point on a map. It’s a territory.

Why age changes the math

The chart you used in your 20s shouldn't be the one you use in your 50s. Perimenopause and menopause change everything. Hormones like estrogen affect where we store fat—usually shifting it toward the abdomen. This is actually a survival mechanism, but it can make the scale creep up.

Research, including studies published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, suggests that for older women, carrying a little extra weight (being in the "overweight" rather than "normal" BMI category) might actually be protective against osteoporosis and some types of frailty. Being "underweight" on a chart as you age can actually be more dangerous than being slightly over.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

What the charts always miss

The biggest flaw? They don't see your heart. They don't see your blood sugar.

You can be "thin" according to a female height weight chart and have metabolic issues, high cholesterol, or poor cardiovascular endurance. Doctors call this "TOFI"—Thin Outside, Fat Inside. Conversely, you can be technically "overweight" but have perfect blood pressure, great stamina, and excellent metabolic health.

We need to talk about Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR). Many experts, like those at the Mayo Clinic, argue that where you carry your weight matters way more than the total number. Fat stored around the midsection (visceral fat) is metabolically active and linked to heart disease. Fat stored on the hips and thighs (subcutaneous fat) is generally considered less risky.

A simple chart doesn't ask where your weight is sitting. It just asks how much gravity is pulling on you.

How to actually use this information

Does this mean the female height weight chart is total garbage? No. It’s a data point. It’s one piece of a very large puzzle. If your weight is significantly outside the range, it’s a reason to ask questions, not a reason to panic.

If you’re looking at a chart, use it as a starting conversation with a professional. Ask about your body fat percentage. Ask about your A1C levels.

Think about your "set point." This is the weight your body naturally wants to maintain when you're eating intuitively and staying active. For some women, that set point is naturally ten pounds higher than what a generic chart suggests. Fighting your biology to hit an arbitrary number on a grid is a losing battle that usually ends in burnout and metabolic damage.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

Real-world variables

- Pregnancy History: Your ribcage can literally expand during pregnancy. Your hips can shift. Your body might never return to its "pre-baby" weight on a chart, and that is biologically normal.

- Ethnicity: BMI-based charts were largely developed using data from European populations. Research has shown that health risks for conditions like Type 2 diabetes can start at lower BMIs for Asian women compared to Caucasian women.

- Hydration and Cycle: A woman can "gain" five pounds of water weight in a single week due to her menstrual cycle. If you weigh yourself on the wrong day, the chart will tell you you've suddenly become unhealthy. It's nonsense.

Better metrics than the scale

If you want a true picture of your health, stop staring at the grid. Try these instead:

The "Stair Test": How do you feel walking up three flights of stairs? If you're "in range" on a chart but winded after one flight, the chart isn't telling the whole story.

Sleep Quality: Are you resting? Weight is often a byproduct of cortisol and sleep. If you're stressed and sleep-deprived, your weight will reflect that, regardless of what the "ideal" says.

Energy Levels: Do you have the energy to do what you love?

Honestly, the best use for a female height weight chart is to treat it like a weather forecast. It gives you a general idea of the conditions, but it doesn't tell you exactly what to wear or how the day will feel.

Actionable Steps for Navigating the Numbers

- Measure your waist-to-hip ratio. Use a flexible tape measure. Divide your waist measurement by your hip measurement. For women, a ratio of 0.85 or lower is generally considered a lower risk for chronic diseases.

- Get a DEXA scan if you’re curious. If you really want to know what's going on, a DEXA scan can tell you your bone density and exactly how much of your weight is muscle vs. fat.

- Focus on functional strength. Instead of chasing a lower number on the chart, aim for a "functional" goal, like being able to carry your own groceries or doing a certain number of pushups.

- Ditch the daily weigh-in. Weight fluctuates too much for daily checks to be useful. If you must use a scale, check once a month at the same time in your cycle to see long-term trends rather than daily noise.

- Consult a weight-neutral provider. If your doctor looks at a female height weight chart and ignores everything else you're telling them, it might be time for a second opinion. Look for providers who focus on "Health at Every Size" (HAES) principles or functional medicine.

The chart is a tool, not a judge. You are a complex biological system, not a coordinate on a graph. Focus on the habits—the movement, the protein, the hydration, and the joy—and let the weight settle where it naturally needs to be. Your health is measured in the quality of your life, not the digits on a display.