You’ve probably seen them in a doctor’s office or a high school biology textbook. Those colorful, slightly clinical illustrations showing a cross-section of a torso. But honestly, most organs in the body diagram female viewers see are oversimplified. They look like a neat game of Tetris where everything has its own little square. Real life is messier. In a real human body, things are crowded, shifting, and constantly pushing against one another.

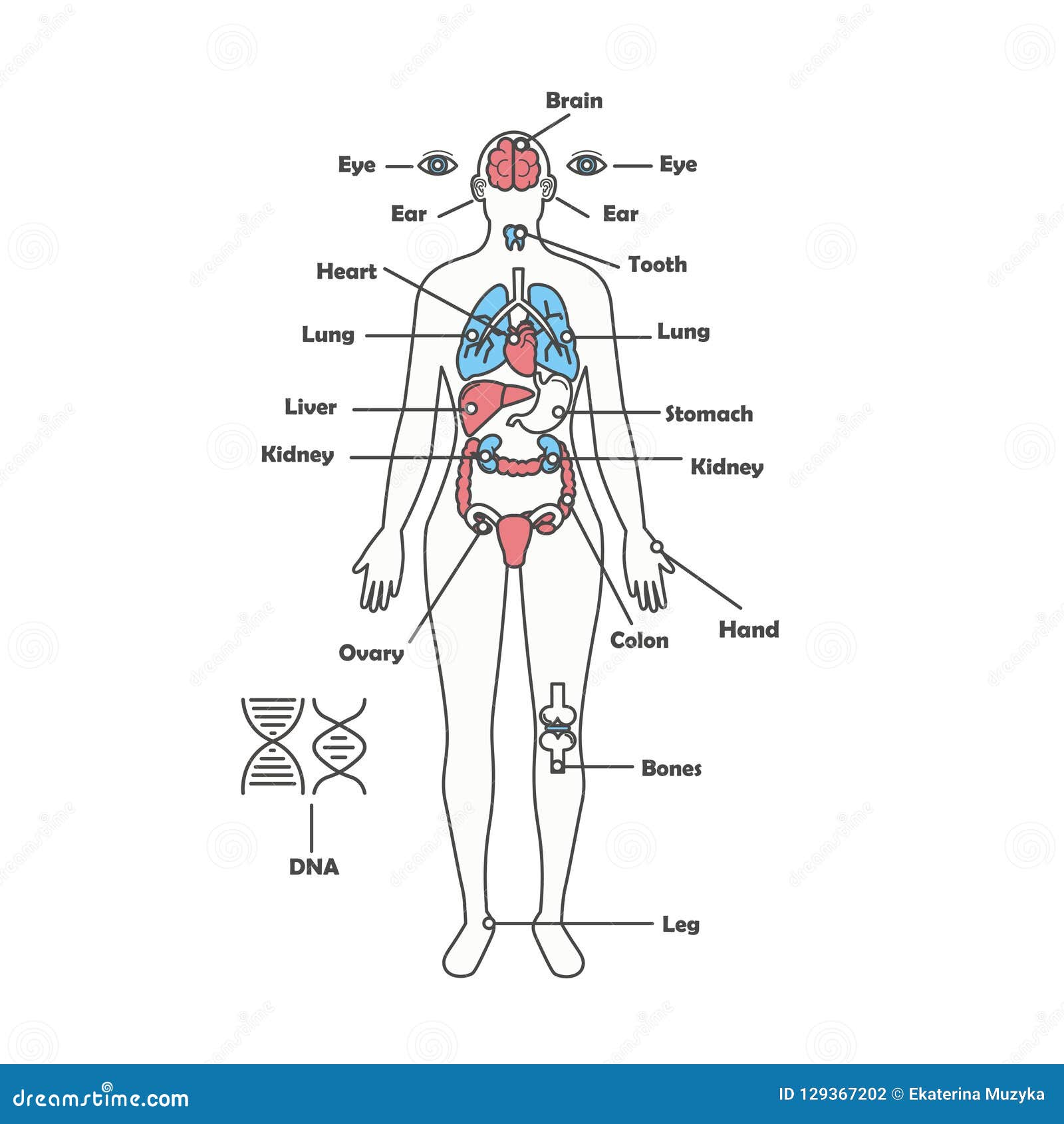

Understanding where your organs actually sit isn't just for passing a test. It’s about knowing why you feel a sharp pinch in your lower right side or why late-stage pregnancy makes it feel like your lungs have shrunk to the size of walnuts. When we look at a diagram, we're looking at a map of our internal survival system. It’s a complex network where the reproductive system, the digestive tract, and the urinary system all fight for a very limited amount of real estate.

The Crowded Neighborhood of the Female Pelvis

The pelvis is arguably the most distinct part of any organs in the body diagram female specific. While everyone has a bladder and a rectum, the female body wedges a whole extra system—the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries—right in the middle of them.

Think of the bladder as sitting right behind the pubic bone. It’s basically a stretchy balloon. Directly behind that is the uterus. This positioning is exactly why many women feel the need to pee every five minutes during the third trimester of pregnancy; the expanding uterus is literally squashing the bladder against the pelvic wall. There’s no "extra" room.

Behind the uterus lies the rectum. This "sandwich" effect means that issues in one organ often mimic issues in another. It’s why doctors sometimes struggle to differentiate between pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and something like appendicitis or even severe irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The nerves are all screaming from the same tiny zip code.

The Ovaries: Floating but Anchored

Ovaries are tiny. Usually about the size of an almond. Yet, they are the hormonal engines of the entire body. In a standard organs in the body diagram female, they look like they’re just hovering at the ends of the fallopian tubes.

They aren’t.

They are held in place by several ligaments, including the ovarian ligament and the broad ligament. These aren’t rigid pipes; they’re flexible. This mobility is actually why some people feel a sharp "twinge" during ovulation, known as Mittelschmerz. The ovary is active, and its proximity to the abdominal lining means any minor irritation is felt immediately.

The Digestive Powerhouse and its Hidden Twists

Moving up from the pelvis, we hit the gut. If you uncoiled the small intestine, it would be about 20 feet long. That’s a lot of tubing to shove into a midsection. In the female body, the arrangement of the large intestine (the colon) is particularly interesting.

🔗 Read more: X Ray on Hand: What Your Doctor is Actually Looking For

Research, including studies often cited by gastroenterologists like Dr. Robynne Chutkan, suggests that the female colon is actually slightly longer on average than the male colon. Why? Possibly to allow for more water absorption during pregnancy. However, because the female pelvis is deeper and contains more organs, that extra length of colon has to "loop" more.

This is a big deal.

More loops mean more places for gas to get trapped and more "tight corners" for waste to navigate. It’s one reason why chronic bloating and constipation are statistically more common in women. When you look at a diagram, the colon looks like a nice, tidy frame around the small intestine. In reality, it’s a winding, redundant path that has to navigate around the reproductive organs.

The Liver and Gallbladder: The Quiet Workers

Under the right side of your ribcage sits the liver. It’s huge. It’s the only organ that can actually regenerate itself. Tucked just beneath it is the gallbladder.

In women, the gallbladder is a frequent troublemaker. Estrogen increases the amount of cholesterol in bile, and it also slows down gallbladder contractions. This is the biological reason behind the "Four Fs" rule that medical students learn regarding gallstones: Female, Forty, Fat (clinically overweight), and Fertile. While that mnemonic is a bit of an oversimplification, the "female" part is rooted in how hormones interact with the organs located in the upper right quadrant of the body diagram.

Breathing and the Heart: The Upper Chamber

The diaphragm is the unsung hero of the organs in the body diagram female. It’s a dome-shaped muscle that separates the chest cavity from the abdominal cavity.

Above it, you have the heart and lungs.

A common misconception is that the heart is on the far left. It’s actually more central, just tilted to the left. In women, the ribcage is often narrower and shorter than in men, meaning the heart and lungs are packed tightly. When you take a deep breath, your diaphragm moves down, pushing your abdominal organs—the stomach, liver, and intestines—outward. This is why "belly breathing" is so much more effective for stress relief than shallow chest breathing; it utilizes the full vertical space of the internal torso.

💡 You might also like: Does Ginger Ale Help With Upset Stomach? Why Your Soda Habit Might Be Making Things Worse

The Urinary System's Short Path

The kidneys are located much higher than most people realize. They aren't in the "lower back" near the waist; they are tucked up under the lower ribs. They filter blood and send urine down the ureters to the bladder.

In females, the urethra—the tube that carries urine out of the body—is significantly shorter than in males (about 1.5 inches versus 8 inches).

This is a crucial anatomical detail.

Because the opening is so close to the vaginal and anal areas, and because the path to the bladder is so short, bacteria have a much easier time traveling upward. This is why Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) are a recurring theme in female health discussions. The diagram shows the proximity, but it doesn't always convey the biological vulnerability that comes with that "short straw" of anatomy.

Why Placement Varies: The Impact of Surgery and Age

We talk about these diagrams like they are permanent. They aren't.

If a woman has a hysterectomy, the space where the uterus used to be doesn't just stay an empty hole. The small intestines move down to fill the gap. This shift can sometimes lead to changes in digestion or pelvic floor pressure.

Age also changes the map.

As we age, ligaments lose elasticity. Organs can actually "drop." This is known as prolapse. The bladder might bulge into the vaginal wall (cystocele), or the rectum might do the same (rectocele). When you look at a diagram of a 20-year-old versus a 70-year-old, the "standard" locations of these organs might be inches apart.

📖 Related: Horizon Treadmill 7.0 AT: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions That Actually Damage Health

Many people assume that if they have pain in their "stomach," it’s their actual stomach.

Usually, it isn't.

The stomach is located quite high, mostly on the left side under the ribs. Pain in the "belly button" area is usually the small intestine. Pain lower down is often the colon or reproductive organs.

- The Appendix Myth: Many people think the appendix is on the left. It’s almost always on the right.

- The Spleen: People forget it exists. It’s on the left, tucked behind the stomach, acting as a massive blood filter.

- The Pancreas: It’s hidden deep behind the stomach. Because it’s so "buried," issues like pancreatic cancer are notoriously hard to detect early because you can’t easily feel a mass there during a physical exam.

Navigating Your Own Anatomy: Actionable Steps

Knowing the layout of the organs in the body diagram female is only useful if you use that knowledge to advocate for yourself.

Track Pain by Quadrant

Instead of telling a doctor "my stomach hurts," divide your torso into four squares in your mind. Is the pain in the Upper Right (Liver/Gallbladder)? Lower Right (Appendix/Ovary)? Upper Left (Stomach/Spleen)? Or Lower Left (Colon/Ovary)? Being specific about the "map" helps doctors narrow down the culprit much faster.

Understand the "Referral" Effect

Sometimes, an organ is hurting, but you feel it somewhere else. This is called referred pain. Gallbladder issues often cause pain in the right shoulder blade. Heart issues in women often manifest as jaw pain or extreme fatigue rather than the classic "chest elephant." If you have persistent pain in a weird spot, don't ignore it just because it's not "where the organ is."

Pelvic Floor Awareness

The organs in the female pelvis are supported by a "hammock" of muscles. If those muscles weaken, everything shifts. Incorporating pelvic floor exercises (like Kegels, but also diaphragmatic breathing) helps keep those organs in their "mapped" positions and prevents the complications of prolapse later in life.

Listen to the "Crowding"

If you feel full after only a few bites of food, it might not just be your stomach. It could be pressure from other organs or even a cyst on an ovary pushing against the digestive tract. The body is a closed system; if one thing gets bigger, something else has to get smaller.

Ultimately, the human body is a masterpiece of spatial engineering. While diagrams give us a general guide, the reality is a shifting, living landscape. Recognizing that your "insides" are a crowded, interconnected community is the first step toward better health literacy.

To take the next step in understanding your internal health, try practicing "body scanning." Lie flat on your back and gently press into different areas of your abdomen, noting where you feel tension or sensitivity. Compare these spots to a high-quality anatomical map to better understand which systems might be reacting to your diet, stress levels, or cycle. If you notice persistent "fullness" or sharp localized pain that doesn't resolve with digestion, consult a healthcare provider with a specific "map" of your symptoms ready to discuss.