The Day Three Brothers Took Over the Grass

Honestly, if you were a fan sitting in the stands at Forbes Field on September 15, 1963, you saw something that sounds like a glitch in a video game. But it wasn't. It was real.

The San Francisco Giants were playing the Pirates. In the bottom of the seventh inning, manager Alvin Dark decided to get weird with his lineup. He moved Felipe Alou to left field. He put his younger brother, Jesus Alou, in right. Then, a few innings later, he pulled the legendary Willie Mays out of center field and plugged in the middle brother, Matty Alou.

Three brothers. One outfield. One team.

It remains one of the most statistically improbable moments in the history of felipe matty jesus baseball lore. We often talk about "baseball families," but the Alous weren't just a family; they were a localized weather event that took over the National League for nearly two decades.

Why the Name "Alou" is Actually a Mistake

You've probably heard them called the Alou brothers your whole life. Here’s the kicker: their name isn't Alou.

Basically, it was a massive clerical error. In the Dominican Republic, the naming convention usually puts the paternal surname first and the maternal surname second. Their father was José Rojas. Their mother was Virginia Alou.

When Felipe Rojas Alou signed with the Giants in the mid-1950s, a scout who didn't understand Dominican culture assumed "Alou" was the last name. He wrote it on the contract. Felipe, just trying to make it in a new country where he didn't speak the language and was facing horrific Jim Crow laws, didn't correct it.

By the time Matty and Jesus arrived, they just rolled with it to keep the "brand" consistent.

The Statistical Madness of felipe matty jesus baseball

These guys weren't just novelties. They were elite.

✨ Don't miss: A qué horas juegan los chiefs: Calendario, canales y lo que debes saber hoy

Felipe was the power-hitting pioneer. He was the first Dominican player to play regularly in the big leagues. He mashed 31 home runs for the Braves in 1966. He was a beast. Then you have Matty, who was a wizard with a toothpick-sized bat. Under the tutelage of Harry Walker in Pittsburgh, Matty transformed into a hitting machine.

Check this out: In 1966, Matty Alou won the National League batting title with a .342 average.

Guess who came in second?

His brother, Felipe, at .327.

Imagine being the third brother, Jesus, and realizing your siblings just went 1-2 in the batting race for the entire league. It’s sort of ridiculous. Jesus was no slouch either—he hit .306 in 1970 and spent 15 years in the bigs.

A Quick Breakdown of the Trio

- Felipe: The leader. 3-time All-Star. 2,101 hits. Later became a legendary manager for the Expos and Giants.

- Matty: The contact specialist. 2-time All-Star. 1,777 hits. Won a World Series with Oakland in '72.

- Jesus: The "best prospect" of the bunch (according to scouts at the time). 2-time World Series champ. 1,216 hits.

Between the three of them, they played 47 seasons. They collected 5,094 hits. That is more than Pete Rose. It's more than Ty Cobb. It's an entire dynasty packed into one generation of brothers from Haina.

The Reality of the 1960s Giants

The Giants of that era were stacked. We’re talking about a team that had Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, and Orlando Cepeda. It’s actually kind of a miracle the Alous got any playing time at all.

Usually, when we talk about felipe matty jesus baseball history, we focus on that one game in '63 where they all stood in the outfield. But the real story is their survival.

Felipe had to deal with being sent to Lake Charles, Louisiana, where Black players weren't allowed to play in the Evangeline League. He had to take 72-hour bus rides. He had to eat in the back of restaurants. He paved the road so Matty and Jesus could follow.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think they were similar players because they were brothers. They weren't.

Felipe was a prototype for the modern corner outfielder—strong, fast, could hit for power. Matty was a "slap" hitter before that was even a common term. He'd choke up on the bat and just spray line drives to left field. Jesus was a free swinger who almost never struck out.

They were three distinct styles of Caribbean baseball converging on the American game at the exact same time.

The Alou Legacy Beyond the 60s

The story doesn't end when they hung up the cleats.

Felipe’s son, Moises Alou, became an absolute superstar in the 90s and early 2000s. He put up numbers that arguably eclipsed his father and uncles. Then you have Luis Rojas, another of Felipe’s sons, who managed the New York Mets.

The Alou tree is massive.

If you look at the Dominican Republic today and see the sheer volume of talent coming out of that country, you have to trace it back to those three guys in the 1960s. They proved that Dominican players weren't just "flashy"—they were durable, professional, and championship-caliber.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of felipe matty jesus baseball, there are a few things you should actually do rather than just reading stats.

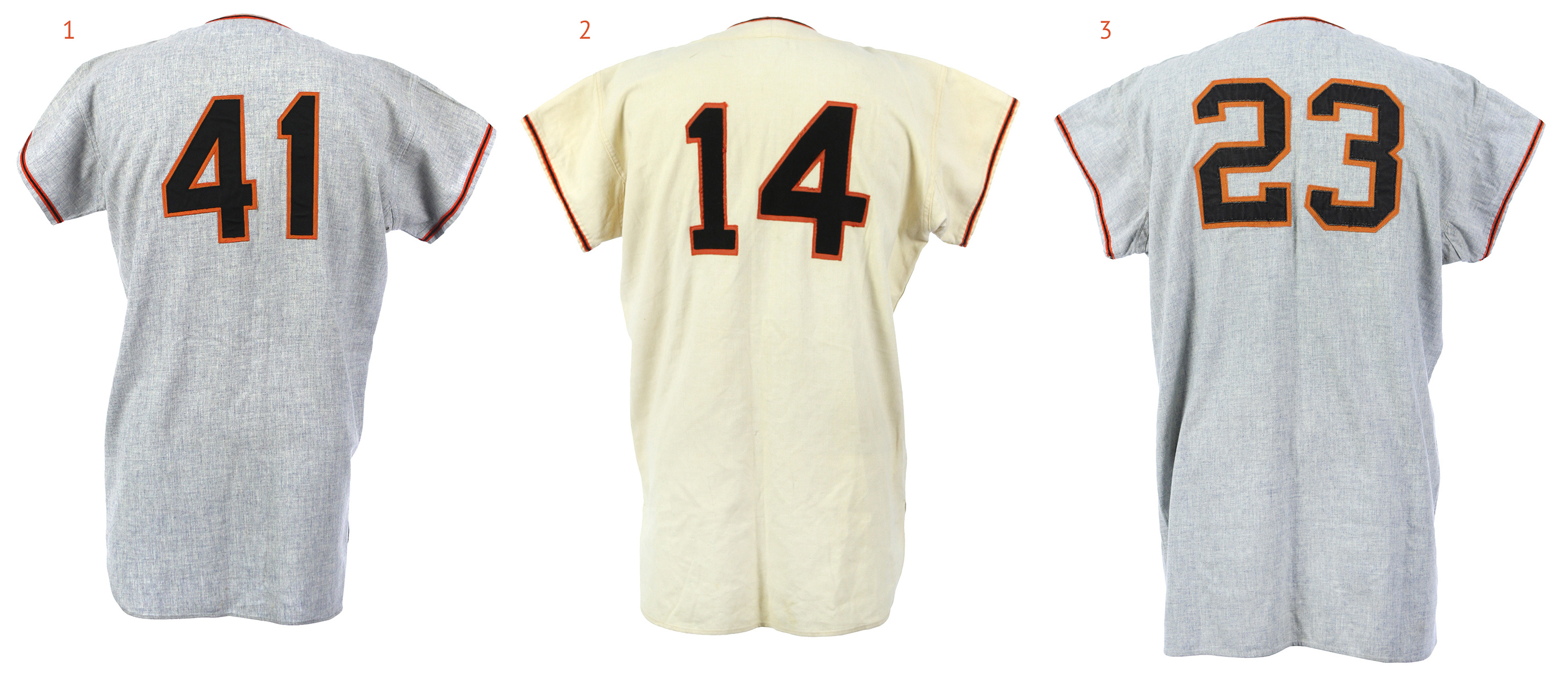

- Look for the 1963 Topps #412: This is a classic card featuring the "Alou Brothers" as a trio. It’s one of the most iconic "multi-player" cards ever made and surprisingly affordable for such a huge piece of history.

- Read Felipe Alou's Memoir: It’s called Alou: My Life and Baseball. Honestly, it’s one of the best sports books ever written because it covers the intersection of the Civil Rights movement and the Latinization of baseball.

- Track the "Brother Hit" Record: While the Alous held the record for most hits by three brothers for a long time, keep an eye on modern families. The Alous set a bar that requires three siblings to all be All-Star caliber for 15+ years—a feat that still hasn't been replicated in the same way.

The Alous weren't just a trivia answer. They were the bridge between the old-school MLB and the global game we see today. They didn't just play baseball; they defined a family business that is still running sixty years later.