If you’ve ever sat in a coffee shop trying to look smart with a copy of Fear and Trembling, you probably realized pretty quickly that Søren Kierkegaard wasn't interested in making your life easy. He was a weird guy. He broke off his engagement to the love of his life, Regine Olsen, for reasons that still make historians scratch their heads, and then he spent the rest of his career basically screaming into the void about faith, anxiety, and why being a "good person" is sometimes the opposite of being a "religious person."

Most people think this book is just a dry retelling of a Bible story. It isn't. It’s a psychological thriller about the absolute terrifying nature of belief.

The Abraham Problem and Why It Freaks Us Out

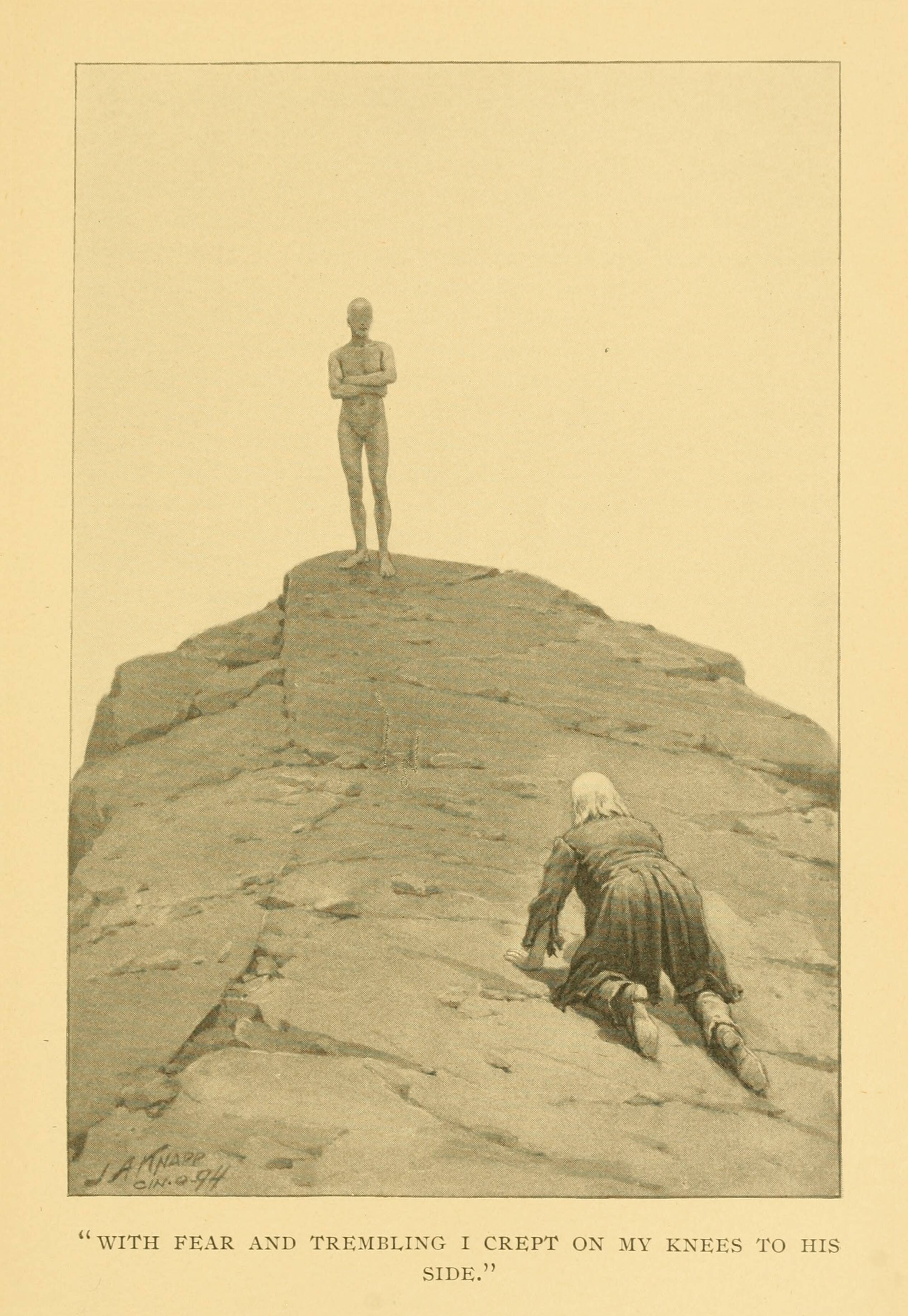

At the heart of Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard (writing under the pen name Johannes de Silentio) fixates on one specific moment: Abraham climbing Mount Moriah with a knife and his son, Isaac.

It’s a brutal story.

If a guy today said God told him to kill his kid, we’d call the police. We’d call him a murderer. Johannes de Silentio acknowledges this. He says that from an ethical standpoint—the rules we use to live in a functioning society—Abraham is a murderer. Period. But from a religious standpoint, he’s the "Father of Faith." This tension is what Kierkegaard calls the "teleological suspension of the ethical."

That’s a fancy way of saying that sometimes, the individual's relationship with the Divine or their own deep, personal truth might actually contradict the moral laws of society. It’s a dangerous idea. It’s why the book is so unsettling. You can’t just "understand" Abraham. If you think you understand him, you probably haven't actually looked at the knife in his hand.

Faith isn't a warm, fuzzy feeling here. It’s a "trembling" because it involves a total surrender of reason. You're jumping into the dark.

💡 You might also like: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Knight of Faith vs. Knight of Infinite Resignation

Kierkegaard draws a sharp line between two types of people. Most of us, if we're honest, are "Knights of Infinite Resignation." This is the person who gives up something they love for a higher cause. Maybe you give up your dream job to take care of a sick parent. It’s sad, it’s noble, and you find a certain peace in the tragedy. You've "resigned" yourself to the loss.

The Knight of Faith is different. They’re basically a paradox.

Abraham gives up Isaac, but he simultaneously believes he will get Isaac back. Not in the afterlife. Not in some metaphorical way. He believes he will have him back in this life, on this earth. Kierkegaard calls this "virtue of the absurd."

Honestly, the most shocking part of the book is how the Knight of Faith looks. He doesn't look like a monk or a tortured artist. Johannes says he looks like a tax collector. He looks like a guy who enjoys his dinner and takes a walk in the park. He’s fully present in the world because he’s already given everything up and received it back from God. It’s a level of psychological freedom that most of us can’t even fathom.

Why Fear and Trembling Still Matters in 2026

We live in a world that demands data, logic, and consensus. Everything has to be "transparent" or "validated" by the group. Kierkegaard is the antidote to that. He argues that the most important parts of being human—the "why" behind our biggest decisions—are often things we can't explain to anyone else.

If you can explain your faith or your deepest convictions perfectly, Kierkegaard might say you don't actually have them. You just have an opinion.

📖 Related: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

The Problem of the "Universal"

Society loves the Universal. The Universal is the set of rules that applies to everyone. Don't lie. Don't steal. Be a "productive member of society." These are good rules. But Kierkegaard warns that if we only live by the Universal, we lose our "I." We become just another cog in the machine.

Abraham’s trial is unique to Abraham. No one else can tell him if he’s doing the right thing. He is "the individual" in the most extreme sense. This is the birth of existentialism. It’s the terrifying realization that you are responsible for your own soul, and no amount of "following the rules" can save you from that responsibility.

Common Misconceptions About the Text

People often think Kierkegaard is saying "go ahead and break the law if you feel like God told you to." That’s a massive misunderstanding. He’s not giving a hall pass to fanatics.

In fact, he spends a lot of time talking about how Abraham suffers. He isn't happy about what he has to do. He’s in agony. The "fear and trembling" isn't a metaphor; it’s a physical reaction to the weight of the task. If someone claims a "divine command" and they’re smug or excited about it, they aren't Abraham. They’re just a narcissist.

Another mistake? Thinking this is a book for "religious people" only. Even if you’re a hard-core atheist, the psychological insights here are gold. It’s about the "leap." Every major life decision—marriage, starting a business, moving across the world—requires a leap where reason stops and action begins. You can’t calculate your way into a meaningful life. At some point, you just have to move.

Real-World Nuance: The Cost of the Leap

It’s worth noting that Kierkegaard’s life was a bit of a mess. He wrote this stuff while he was still reeling from his breakup with Regine. Some critics, like Walter Lowrie or even modern scholars like Clare Carlisle, point out that Fear and Trembling might be a giant, sophisticated "it’s not you, it’s me" letter. He’s trying to justify why he had to leave her to pursue his "calling."

👉 See also: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Does that make the philosophy less valid? Not necessarily. But it adds a layer of human messiness. It shows that even the greatest thinkers use philosophy to navigate their own heartbreak.

How to Actually Approach the Book

If you’re going to read it, don't start with a commentary. Just dive in. Here’s a bit of advice on how to handle the "Silentio" style:

- Read the "Attunement" section slowly. He gives four different versions of the Abraham story. Each one is a "what if." What if Abraham was angry? What if Isaac lost his faith? It’s meant to disorient you.

- Don't worry about the Greek references. He drops names like Heraclitus and Agamemnon constantly. You don't need a PhD to get the point. He’s comparing Abraham to "tragic heroes" who sacrifice for the state, whereas Abraham sacrifices for a private, absolute relationship.

- Look for the humor. Believe it or not, Kierkegaard is funny in a dark, biting way. He hates the "system" of Hegel and the "Sunday Christians" of his time. He’s constantly poking fun at people who think they can understand God through a textbook.

Practical Insights for Your Own Life

Reading Fear and Trembling shouldn't just be an academic exercise. It’s meant to change how you see your own choices.

- Own your "Leaps." Stop waiting for 100% certainty before you make a move. Certainty is a myth. Whether it’s a career change or a personal commitment, recognize that the "trembling" is a sign that the choice actually matters.

- Distinguish between Ethics and Faith. Sometimes being "nice" or "polite" is just a way of hiding from what you actually know is right. This doesn't mean being a jerk; it means recognizing that your deepest values might not always align with what’s socially convenient.

- Value the Individual. In an age of algorithms, remember that you are not a data point. Your internal life is "higher than the universal." Don't let the noise of the crowd drown out the "quiet" demands of your own conscience.

The book ends without a neat little bow. It doesn't give you a "how-to" guide. It leaves you on the mountain with Abraham, the knife, and the silence. That’s the point. The silence is where the work begins.

To truly engage with the text, grab a copy—the Alastair Hannay translation is usually the go-to for a balance of accuracy and readability—and read the "Problemata" sections. These are the core arguments. Focus on "Problem II: Is there an absolute duty to God?" and sit with the discomfort. Don't try to solve the paradox; try to live within it.