You’re staring at a screen. Maybe it’s a medical lab report, a security alert at your job, or just a "spam" folder that seems a little too full. You see a result. It says "Yes" or it says "No." You trust it because, well, that’s what machines are for, right? Wrong.

Numbers lie. Or rather, they don't lie, but they certainly mislead.

In the world of statistics and data science, we live and die by the binary. But the truth is rarely a straight line. When we talk about false positive and negative results, we’re actually talking about the gap between what a test says and what is actually happening in the real world. It’s the difference between a smoke alarm going off because you burned toast (false positive) and a silent alarm while the curtains are literally on fire (false negative). One is annoying. The other is a catastrophe.

The Mental Trap of the "Clear" Result

Most people think of tests as a light switch. On or off. But every diagnostic tool, from a COVID-19 rapid test to a credit card fraud detection algorithm, has a "threshold." If you set the threshold too low, you catch every single bad guy, but you also arrest half the innocent neighborhood. If you set it too high, your system is "clean," but the burglars are walking out the front door with your TV.

This isn't just academic.

In 2015, the American Cancer Society had to adjust its guidelines for mammograms. Why? Because the rate of false positives was causing "unnecessary anxiety" and lead to invasive biopsies that people didn't actually need. They realized that by trying to catch everything (reducing false negatives), they were creating a secondary crisis of over-diagnosis. It’s a brutal, high-stakes balancing act that engineers and doctors play every single day.

How False Positives Ruin Your Workflow

A false positive is a "Type I error." Think of it as a "cry wolf" scenario.

In cybersecurity, this is the bane of an analyst's existence. Imagine an intrusion detection system (IDS) that flags every single employee who forgets their password as a "State-Sponsored Hacker." After the fiftieth alert of the morning, the human analyst stops looking. They get "alert fatigue." This is exactly what happened in the famous 2013 Target data breach. The system actually did flag the intruders. But because the system threw so many false positives every day, the warnings were basically ignored.

The "cost" here isn't just a wrong answer; it's the erosion of trust in the system itself.

When a developer sees a "failing" build in their CI/CD pipeline that turns out to be a flaky test rather than a real bug, they start to ignore the red icons. You’ve basically trained your team to be blind. Honestly, it’s better to have no alert at all than a constant stream of lies.

The Quiet Danger of the False Negative

Now, flip the coin. A false negative (Type II error) is when the test says "All good!" but everything is very much not good.

This is the silent killer. In medical screening, this is the tumor that doesn't show up on the scan because it’s the same density as the surrounding tissue. In airport security, this is the forbidden item that looks like a bottle of shampoo on the X-ray.

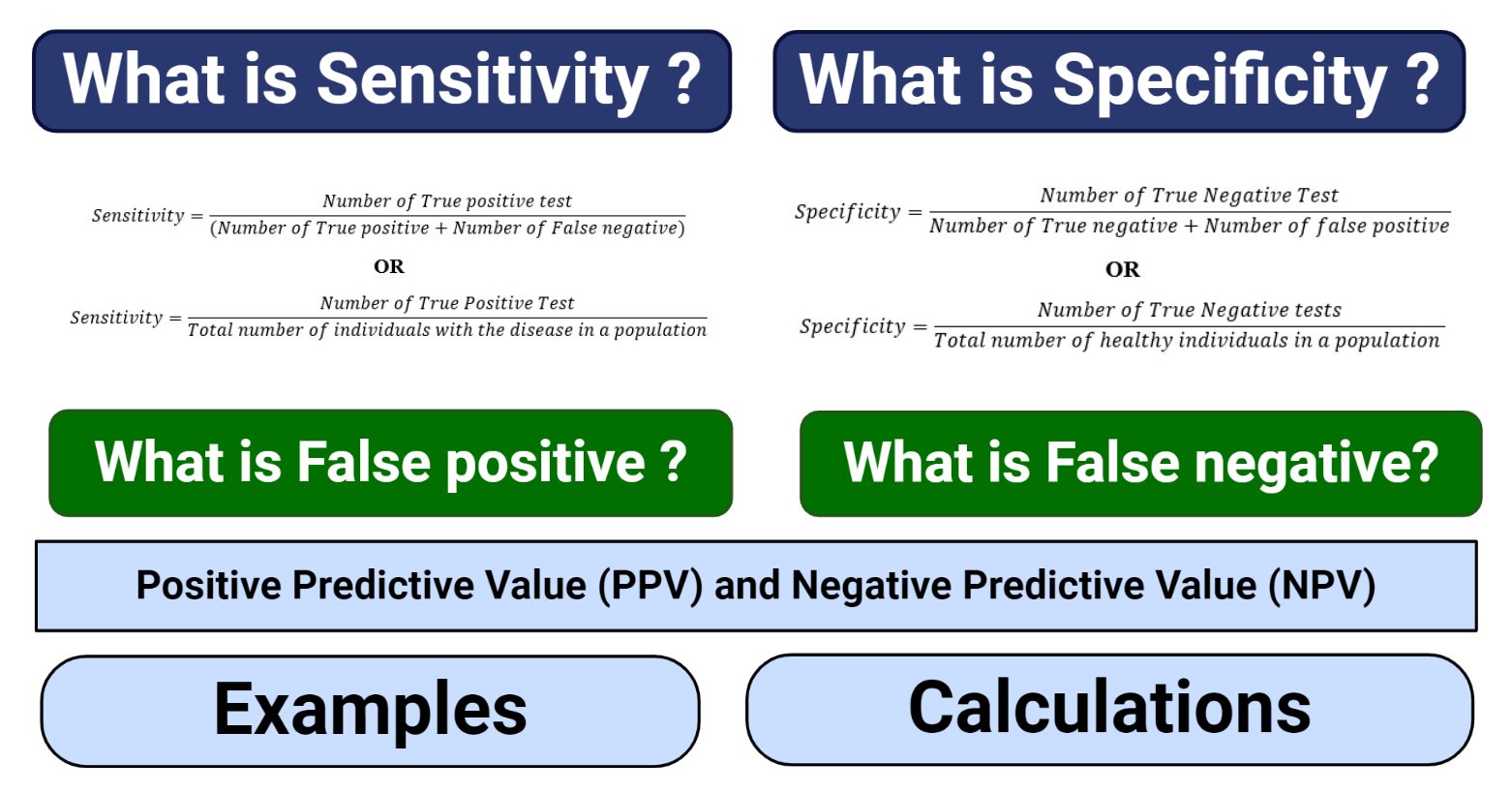

Statistically, we call the ability to avoid false negatives "sensitivity." A highly sensitive test is great at finding the needle in the haystack. But—and here is the catch—sensitive tests are usually the ones that trigger the most false positives. You can't usually have one without the other.

Let's look at the "Spam" folder in your email.

- False Positive: That job offer ended up in Spam. You missed the interview. Bad.

- False Negative: A phishing link ended up in your Inbox. You clicked it. Your bank account is empty. Also bad.

Which one is worse? It depends on your "Risk Appetite." If you're a doctor, a false negative on a treatable disease is the ultimate failure. If you're a judge, a false positive (convicting an innocent person) is often seen as the greater moral sin, though the legal system struggles with this daily.

Precision vs. Recall: The Tug of War

If you want to sound like a real expert in false positive and negative theory, you have to talk about Precision and Recall. They are the two ends of a see-saw.

Precision is basically: "Of all the times I said 'Yes,' how many were actually 'Yes'?"

Recall (Sensitivity) is: "Of all the actual 'Yes' cases out there, how many did I find?"

Imagine you’re fishing with a net. If you use a net with tiny holes, you’ll catch every fish in the lake (High Recall). But you’re also going to catch old boots, tires, and seaweed (Low Precision). If you use a spear, you’ll only get the fish you point at (High Precision), but you’re going to miss a lot of fish that swim by while you’re aiming (Low Recall).

Modern AI—like the stuff powering self-driving cars—is constantly tweaking this. A car that slams on the brakes for a shadow (false positive) will get rear-ended. A car that thinks a white truck is just the bright sky (false negative) will crash. This happened with Tesla's Autopilot in 2016 in Florida. The system failed to distinguish a white tractor-trailer against a bright sky. That’s a fatal false negative.

✨ Don't miss: The Definition of Technology: What Most People Get Wrong

The "Base Rate" Fallacy: Why Your Brain is Bad at This

Here is where it gets weird. Even a "99% accurate" test can be mostly wrong.

Let’s say there’s a super rare disease that only 1 in 10,000 people have. You take a test that is 99% accurate. It comes back positive. You’re terrified, right?

Don't panic yet.

Because the disease is so rare, out of 10,000 people, the test will correctly identify the 1 person who has it. But, because it's only 99% accurate, it will also say that 1% of the healthy people (about 100 people) have it.

So, your "Positive" result actually only has a 1 in 101 chance of being true. This is called the Base Rate Fallacy. Most people—including many doctors, unfortunately—forget to factor in how common the thing is in the first place. When the "thing" is rare, false positives will almost always outnumber the real cases, even with a "great" test.

Practical Steps to Manage the Chaos

You can't eliminate errors. You can only choose which ones you're willing to live with. To handle false positive and negative outcomes in your own life or business, you need a strategy.

Audit your "Sensitivity" levels.

If you are getting too many notifications on your phone or work dashboard, your "Recall" is too high. You are drowning in noise. Turn the threshold up. It’s okay to miss a few "FYI" emails if it means you actually see the "Emergency" ones.

Implement "Defense in Depth."

Never rely on a single test for something critical. In medicine, a positive screening test (like a PSA test for prostate cancer) is almost always followed by a different kind of test (like a biopsy). This "Sequential Testing" uses the second test to filter out the false positives of the first.

Calculate the Cost of Being Wrong.

Sit down and ask: "What happens if I miss this?" vs. "What happens if I falsely flag this?"

If you’re building a credit card fraud system, the cost of a false positive is a frustrated customer at a grocery store. The cost of a false negative is the bank losing $5,000. Banks usually lean toward the false positive (blocking the card) because it’s cheaper to apologize to you than to lose the cash.

Look at the "F1 Score."

In data science, we use something called the F1 Score to find the "sweet spot" between precision and recall. It’s a single number that tells you how well your system is balancing the two. If you’re hiring or evaluating software, ask for the F1 score, not just the "Accuracy." Accuracy is a vanity metric; F1 is the real world.

🔗 Read more: Safari Updates for Mac: What Really Matters in the 2026 Refresh

Don't ignore the "Null Hypothesis."

Always start with the assumption that nothing is happening. If your data tells you something "Significant" is going on, be a skeptic. Ask if the result could just be a fluke of the sample size. The more things you test for, the more likely you are to find a false positive just by pure "luck." This is why scientists have to be so careful with "p-values"—if you test 20 different jelly beans to see if they cause acne, one of them will likely "show" a link just by chance.

Stop looking for the perfect test. It doesn't exist. Instead, start looking for the "Least Bad" mistake. Once you know which error you’d rather make, the data becomes a lot easier to read.