You probably haven't thought about your fallopian tube since high school biology. Most people don't. We focus on the uterus because that’s where the baby grows, or the ovaries because that’s where the hormones live. But honestly? The fallopian tubes are the real MVPs of the reproductive system. They aren't just passive "pipes." They are active, muscular, and incredibly sophisticated organs that act as a high-speed transit system for life itself.

Think of them as the original Tinder. This is where the egg and the sperm actually meet. If the tube isn't working, the rest of the system basically hits a dead end.

What is a fallopian tube exactly?

It’s a pair of flexible, four-inch-long tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus. But "connect" is a bit of a misnomer. Fun fact: the tubes aren't actually physically attached to the ovaries. They just sort of hover nearby, waiting for an egg to show up. It’s like a hand waiting to catch a baseball.

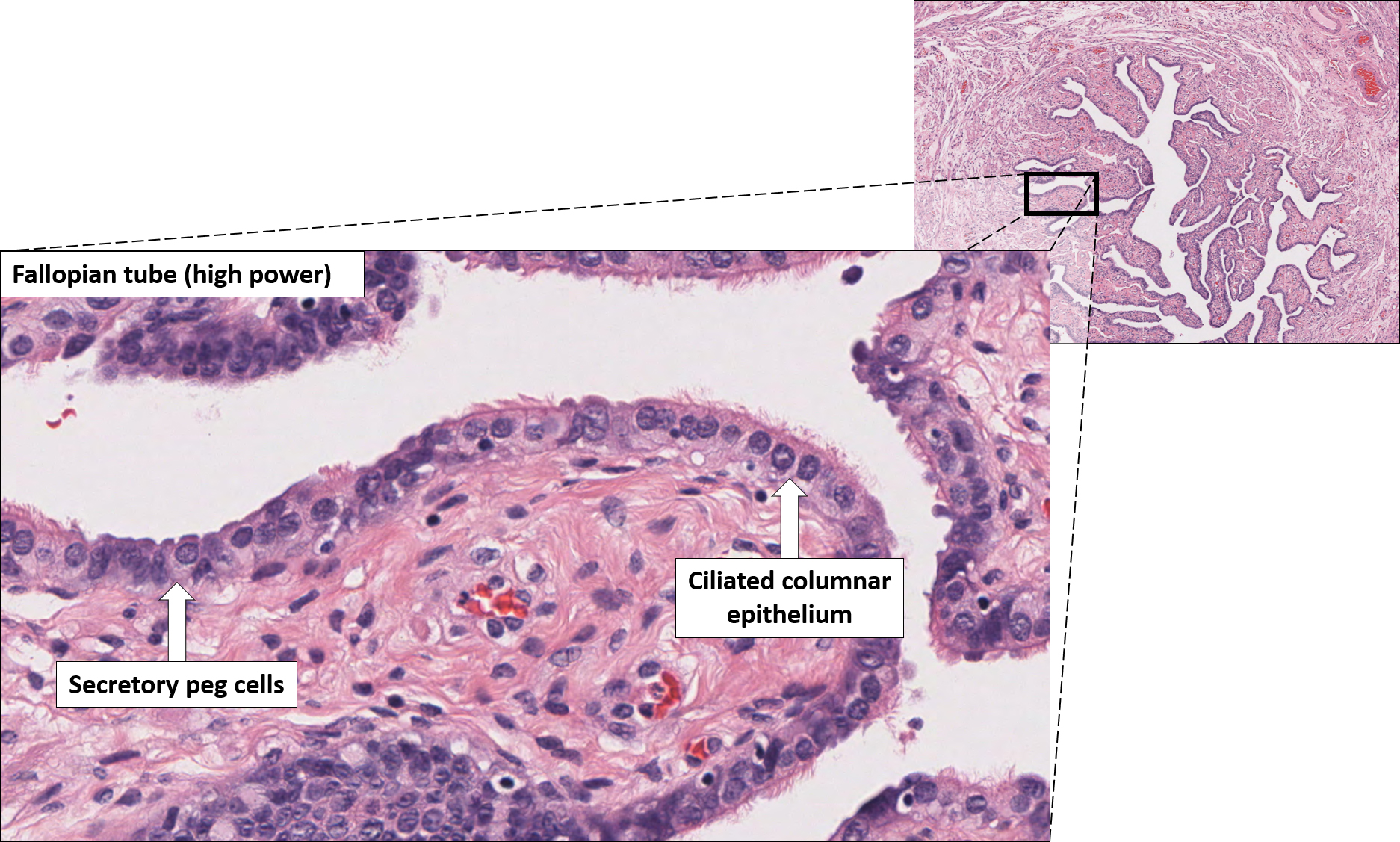

Each fallopian tube is lined with millions of tiny, hair-like structures called cilia. These cilia beat in a rhythmic wave, creating a current that sweeps the egg toward the uterus. Without this movement, the egg would just sit there. Or worse, it would get lost in the pelvic cavity.

The anatomy is surprisingly complex. You’ve got the infundibulum, which is the funnel-shaped end near the ovary. Then there are the fimbriae—these look like tiny fingers or fringe. When ovulation happens, these fimbriae get active. They swell with blood and start sweeping the surface of the ovary to "suck up" the egg.

Why the Ampulla matters most

If you want to get technical, the ampulla is the widest part of the tube. This is the "Goldilocks zone." It’s where fertilization usually happens. If a sperm is going to meet an egg, it’s going to happen right here in the curve of the fallopian tube.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Right Care at Texas Children's Pediatrics Baytown Without the Stress

It’s a race against time. An egg only lives for about 12 to 24 hours after release. The sperm has to swim through the cervix, across the entire uterus, and up into the tube to find it. The tube provides the perfect chemical environment to keep that sperm alive and kicking until the egg arrives.

When things go sideways: Ectopic pregnancies and blockages

The tube is narrow. Like, really narrow. The internal diameter is roughly the thickness of a sewing needle in some spots. This is why things can go wrong so easily.

If a fertilized egg—now an embryo—gets stuck on its way to the uterus, it might try to implant right there in the tube wall. This is called an ectopic pregnancy. It’s a medical emergency. The fallopian tube isn't designed to stretch like the uterus. If the embryo grows too large, the tube can rupture.

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) is one of the biggest threats to tube health. Usually caused by untreated STIs like chlamydia or gonorrhea, PID causes massive inflammation.

- Scar tissue (adhesions) can form inside the tube. Even a tiny bit of scarring can act like a roadblock.

- Endometriosis is another culprit. Tissue similar to the uterine lining can grow on the outside of the tubes, kinking them or pulling them out of place.

It's wild how much can happen in such a small space. A lot of people don't realize they have a "blocked tube" until they try to get pregnant and find they can't. This is known as tubal factor infertility. It accounts for about 25% to 30% of all infertility cases. That's a huge number.

Can you live with just one?

Yes. Absolutely.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Healthiest Cranberry Juice to Drink: What Most People Get Wrong

The body is weirdly resilient. If one fallopian tube is removed—say, because of an ectopic pregnancy or a cyst—the remaining tube can often "reach over" and pick up an egg from either ovary. It sounds like science fiction, but the tubes are mobile. They can move around in the pelvic cavity quite a bit.

Surgeons like Dr. Mary Jane Minkin, a clinical professor at Yale, often point out that as long as you have one healthy tube and one functioning ovary, your fertility usually remains relatively high. You don't necessarily lose 50% of your fertility just because you lost one tube.

The connection to Ovarian Cancer

Here is something most people don't know: Many "ovarian" cancers actually start in the fallopian tube.

In the last decade, researchers have found that the most common and aggressive type of ovarian cancer (high-grade serous carcinoma) often begins in the fimbriae of the tube. The cancer cells then migrate to the ovary. This discovery has changed how some surgeries are done. Nowadays, if a woman is having a hysterectomy but wants to keep her ovaries for hormonal health, surgeons often recommend a salpingectomy—removing just the tubes—to drastically reduce the future risk of cancer.

Keeping your tubes healthy

You can't really "exercise" your tubes. There’s no "tube yoga." But you can protect them.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Hybrid Athlete Training Program PDF That Actually Works Without Burning You Out

First, get tested. Seriously. STIs are often silent. Chlamydia can hang out in your system for years without a single symptom, all while it’s slowly scarring the delicate lining of your fallopian tube. Regular screenings are the best defense.

Second, if you have severe period pain, talk to a doctor about endometriosis early. The longer it goes untreated, the more likely it is to cause "cobwebbing" or adhesions around your reproductive organs.

Modern diagnostic tools

If a doctor suspects a problem, they usually use a test called an HSG (hysterosalpingogram). It’s basically an X-ray where they inject a special dye through the cervix. If the dye flows out the ends of the tubes, they’re open. If it stops? You’ve got a blockage. It's not the most comfortable procedure—it feels like intense period cramps—but it's the gold standard for seeing what's actually happening in there.

Another option is a laparoscopy. This is a minor surgery where they put a camera through your belly button. It's the only way to see if there is scar tissue on the outside of the tubes that might be pulling them out of alignment.

Next Steps for Your Reproductive Health

- Schedule a screening: If you haven't had a full STI panel in the last year, book one. It's the most proactive thing you can do for your tubal health.

- Track your ovulation: Understanding when you ovulate helps you know when your tubes are "active."

- Discuss "Opportunistic Salpingectomy": If you are already planning a pelvic surgery or permanent birth control (like getting your "tubes tied"), ask your doctor about removing the tubes entirely instead of just clipping them. This significantly lowers ovarian cancer risk.

- Monitor persistent pelvic pain: Don't ignore "pinching" or localized pain that happens every month; it could be a sign of adhesions or tubal issues that need professional imaging.

The fallopian tube is a master of micro-engineering. It manages pH levels, provides nutrients to a traveling embryo, and facilitates the very beginning of human life. Treat them well.