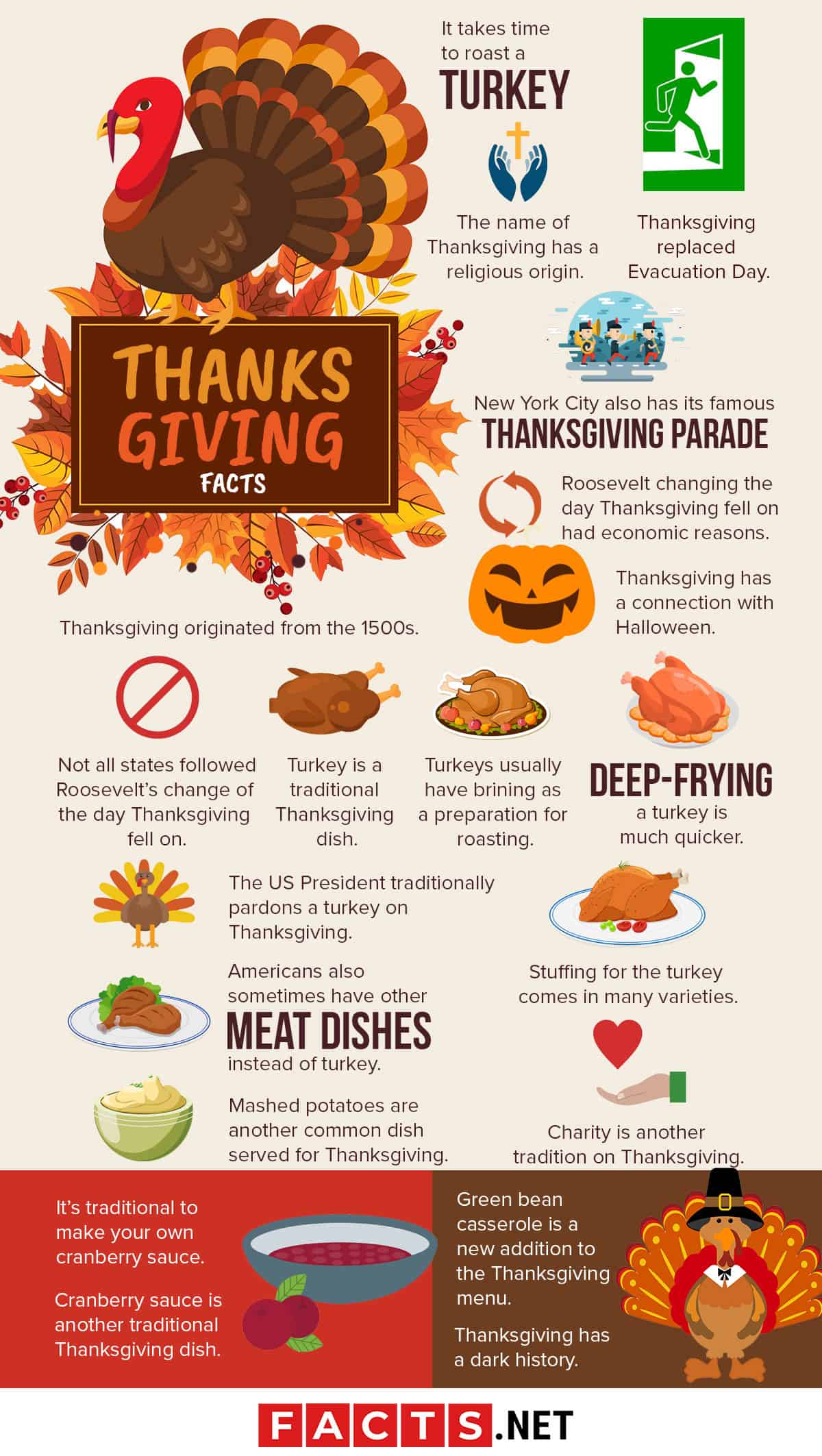

Most people think they know the story. You’ve seen the construction paper hats and the hand-drawn turkeys since you were five. It’s the classic American myth: a friendly dinner, some shared corn, and everyone lived happily ever after. Except history is rarely that clean. When you look at the actual facts about Thanksgiving history, the reality is way more complicated, a bit darker, and honestly, much more interesting than the sanitized version we get with our pumpkin pie.

History isn't a straight line. It's a messy web of politics, survival, and accidental traditions.

The 1621 Feast Wasn’t Actually "Thanksgiving"

If you could travel back to Plymouth in the autumn of 1621, and you asked a Pilgrim about their "Thanksgiving" feast, they’d look at you like you had two heads. For the English Separatists, a "Day of Thanksgiving" was a religious event. It involved fasting and long, grueling hours of prayer. It was solemn. It was quiet. It was definitely not a party. What happened in 1621 was a secular harvest celebration.

The Wampanoag weren’t even technically "invited" to a dinner party. That’s a common misconception.

Edward Winslow, who was actually there, wrote about it in Mourt’s Relation. He mentions that Governor Bradford sent four men on a "fowling" mission so they could celebrate the harvest. When the Pilgrims started firing their guns in celebration, the Wampanoag leader, Massasoit, showed up with about 90 men. Why? They probably thought a war was starting. Once they realized it was just a festival, they stuck around. They even contributed five deer to the pile of food. It was a three-day diplomatic crossover event, not a suburban potluck.

No Turkey? No Problem.

We’re obsessed with the bird. But back then? Turkey was just an "also-ran."

👉 See also: AP Royal Oak White: Why This Often Overlooked Dial Is Actually The Smart Play

Winslow’s letters mention "wild fowl," which could have been turkey, sure, but it was just as likely to be duck, goose, or even the now-extinct passenger pigeon. The real stars of the menu were probably things that would gross out a modern kid. We’re talking about eel, mussels, and lobster. New England was crawling with seafood.

And forget the cranberry sauce. The Pilgrims had cranberries, but they didn't have the sugar required to make that jelly-like canned stuff we love today. They also didn't have butter or flour for pie crusts. So, the "first" Thanksgiving was basically a giant seafood boil with some venison and boiled corn on the side. No mashed potatoes either—potatoes hadn't really made their way to that part of North America yet.

The Darker Turn of 1637

It’s uncomfortable, but we have to talk about it. While 1621 was relatively peaceful, the relationship between the settlers and the Indigenous people soured fast. By 1637, things had turned violent.

The Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, officially declared a "Day of Thanksgiving" to celebrate the return of colonial hunters who had just massacred a Pequot village. This is where the narrative gets heavy. For many Indigenous people today, Thanksgiving isn’t a day of gratitude; it’s a National Day of Mourning. This tradition started in 1970 in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to remind people that the "peace" of the 1620s was a fleeting moment in a much longer history of displacement and conflict.

Ignoring this side of the story doesn't make the holiday better; it just makes our understanding of it shallow.

✨ Don't miss: Anime Pink Window -AI: Why We Are All Obsessing Over This Specific Aesthetic Right Now

Sarah Josepha Hale: The Godmother of the Turkey

If you want to blame someone for the modern holiday, don’t look at the Pilgrims. Look at Sarah Josepha Hale. She was the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book and she was a powerhouse.

For 36 years, she lobbied every president she could find to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. She wrote thousands of letters. She saw it as a way to unify a country that was literally tearing itself apart over the issue of slavery. Before her campaign, Thanksgiving was mostly a "New England thing" that Southerners largely ignored.

Abraham Lincoln finally listened in 1863. He was in the middle of the Civil War. He needed a win. He needed a way to foster a sense of national identity. So, he issued the proclamation that set the last Thursday of November as the day.

Why the Date Kept Shifting

Lincoln set the date, but it wasn't set in stone. In 1939, during the tail end of the Great Depression, retailers were panicked. Because November had five Thursdays that year, the holiday was going to fall late, leaving very little time for Christmas shopping. They begged Franklin D. Roosevelt to move it up.

FDR complied. He moved Thanksgiving up a week.

🔗 Read more: Act Like an Angel Dress Like Crazy: The Secret Psychology of High-Contrast Style

People lost their minds. Critics called it "Franksgiving." Some governors refused to recognize the change, so for a couple of years, the U.S. actually had two different Thanksgivings depending on which state you lived in. Eventually, Congress stepped in and passed a law in 1941 to lock in the fourth Thursday of November forever.

The Evolution of the Football Connection

Football and Thanksgiving go together like gravy and... well, more gravy. But this wasn't an accidental pairing. The tradition actually started in 1876 with the Intercollegiate Football Association championship. By the late 19th century, it was a massive "event" for the social elite in New York.

The Detroit Lions started their tradition in 1934. The owner, George A. Richards, wanted to drum up fans for a team that nobody really cared about at the time. He used his connections in radio to broadcast the game nationally, and it stuck. Now, the Lions and the Dallas Cowboys are essentially the "official" teams of the holiday, whether they're having a good season or not.

Real Facts About Thanksgiving History: Quick Hits

- The "Silent" Century: After the 1621 feast, there wasn't another similar celebration for years. It wasn't an annual thing initially.

- The Macy’s Parade: It didn't start with balloons. In 1924, it was the "Macy’s Christmas Parade" and featured live animals—including bears and lions—from the Central Park Zoo.

- Fork-less Dining: The Pilgrims didn't use forks. They used knives, spoons, and their fingers. Big linen napkins were essential because things got messy.

- George Washington's Role: He was actually the first president to call for a national day of thanks in 1789, but it didn't become a recurring yearly event until Lincoln.

Navigating the Myth vs. The Reality

So, why does any of this matter? Because when we treat the facts about Thanksgiving history like a fairy tale, we miss the human element. The Pilgrims weren't pioneers of religious freedom in the modern sense; they were a specific group of radicals trying to build a very specific, very strict society. The Wampanoag weren't just "helpers"; they were a sophisticated nation navigating a geopolitical crisis.

When you sit down to eat this year, you don't have to feel guilty, but you should probably feel informed. The holiday is a patchwork quilt of 17th-century survival, 19th-century nationalism, and 20th-century consumerism.

Actionable Next Steps for a Better Thanksgiving

If you're looking to honor the history more authentically this year, here are a few things you can actually do:

- Research the Land: Use resources like Native-Land.ca to find out which Indigenous groups traditionally lived where you are sitting right now. It’s a small way to acknowledge the people who were there before the "feasts" began.

- Read Primary Sources: Instead of just taking a textbook's word for it, look up the text of the Pilgrim Hall Museum archives. Reading Winslow’s actual words from 1621 gives you a much clearer picture of the atmosphere.

- Diversify Your Menu: Since the original meal was heavy on local New England ingredients, try incorporating something "historic" like succotash (a mix of corn and beans) or a seafood dish. It’s a great conversation starter.

- Support Indigenous Creators: If you're decorating or buying gifts, look for Indigenous-owned businesses. This shifts the holiday from a performance of the past into a way to support the present-day descendants of the people involved in the story.

History isn't something that happened "back then." It's something we carry with us. Knowing the truth doesn't ruin the holiday; it just makes the gratitude a little more honest.