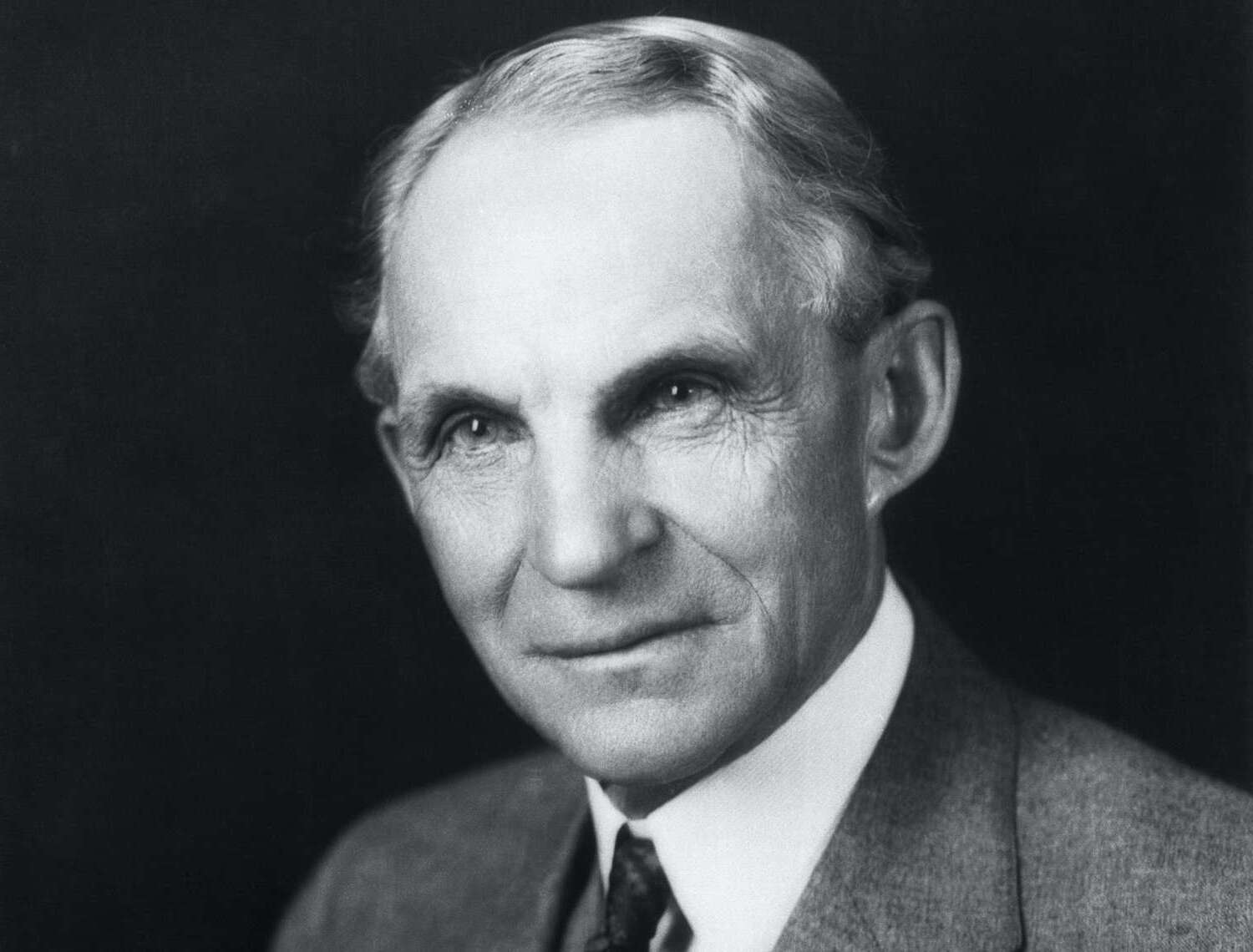

You probably think of Henry Ford as the guy who invented the car. He didn’t. Not even close. Karl Benz usually gets that credit for his Motorwagen back in 1886. But what Ford did was arguably more explosive: he turned a rich man's toy into a middle-class right. When we look at facts about Henry Ford, we aren't just looking at automotive history; we are looking at the DNA of the modern world, for better or worse.

He was a farm boy who hated farming. He was a mechanical genius who struggled to read a blueprint. He was a pacifist who built war machines. Honestly, Ford was a walking contradiction who basically bullied the 20th century into existence through sheer, stubborn will.

The $5 Day Wasn't Charity

If you’ve ever heard someone praise Ford’s "generosity" for doubling his workers' wages to $5 a day in 1914, they’re missing the point. It wasn't about being a nice guy. It was about survival.

Ford’s assembly line was so mind-numbingly boring and physically taxing that people were quitting in droves. In 1913 alone, the Ford Motor Company had to hire 52,000 people just to keep a workforce of 14,000 active. The turnover rate was a staggering 370%.

He realized that if he paid people enough to tolerate the misery of the line, they’d stay. Plus—and this is the clever bit—they could eventually afford to buy the cars they were building. It was a closed-loop economic engine. But there was a catch. To get that $5, workers had to submit to the "Sociological Department." This meant Ford’s investigators could show up at your house to check if you were drinking too much, if your home was clean, or if you were sending money back to your home country instead of "Americanizing." If your lifestyle didn't meet his moral standards, you didn't get the raise.

The Model T Obsession and the Fall of an Empire

The Model T was a masterpiece of simplicity. Between 1908 and 1927, Ford built 15 million of them. At one point, half the cars on the entire planet were Fords.

📖 Related: Reading a Crude Oil Barrel Price Chart Without Losing Your Mind

"Any customer can have a car painted any color he wants so long as it is black."

He actually said that. Why black? Because black enamel paint dried the fastest on the assembly line. Efficiency was his god, and he worshipped at its altar until it almost destroyed him.

By the mid-1920s, the world was moving on. General Motors, led by Alfred P. Sloan, started offering different colors, styling updates, and—critically—credit. Ford hated debt. He refused to change the Model T for nearly two decades. His son, Edsel, practically begged him to modernize. Henry responded by humiliating Edsel in front of executives. He was so convinced that the Model T was "the perfect car" that he let Chevrolet eat his lunch for years before finally, begrudgingly, launching the Model A in 1927.

Fordlandia: The Jungle Failure

Have you ever heard of the time Henry Ford tried to build a Midwestern town in the middle of the Amazon rainforest? It sounds like a fever dream, but it's one of the most fascinating facts about Henry Ford.

In the late 1920s, the British had a monopoly on rubber. Ford hated being beholden to anyone. So, he bought a massive tract of land in Brazil to grow his own rubber trees. He didn't just build a plantation; he built "Fordlandia."

👉 See also: Is US Stock Market Open Tomorrow? What to Know for the MLK Holiday Weekend

It had:

- Paved streets and sidewalks.

- White clapboard houses.

- A hospital and a golf course.

- Square dancing on Friday nights (Ford obsessed over square dancing because he thought jazz was "sinful").

It was a total disaster. He forced Brazilian workers to eat American food like oatmeal and canned peaches in the tropical heat. They hated it. They eventually rioted in 1930, shouting "Brazil for Brazilians!" Furthermore, Ford ignored the local experts; he planted the rubber trees too close together, and blight wiped them out. He poured millions into the jungle and never visited the place once.

The Darker Side of the Legend

We can't talk about Ford without addressing the elephant in the room: his virulent antisemitism. This isn't just a "product of his time" thing; he was extreme even by the standards of the 1920s.

Ford bought a newspaper called the Dearborn Independent. For years, it published a series of articles titled "The International Jew," which relied on the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion. He used his vast dealership network to distribute these papers across the country.

It’s a historical fact that Adolf Hitler admired Ford. Hitler even kept a life-sized portrait of Ford in his office in Munich. In 1938, the Nazi regime awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest honor they could bestow on a foreigner. While Ford later issued a formal apology after a lawsuit, many historians, including Max Wallace in The American Axis, argue that the damage had already been done, fueling conspiracy theories that persist to this day.

✨ Don't miss: Big Lots in Potsdam NY: What Really Happened to Our Store

Strange Habits and Curiosities

- He was a soy obsessed: Long before soy milk was a grocery store staple, Ford was obsessed with the soybean. He wore a suit made of soy fibers and even served an all-soy dinner at the 1934 World's Fair (including soy ice cream).

- The "Last Breath" of Thomas Edison: Ford’s best friend was Thomas Edison. When Edison died in 1931, Ford allegedly asked Edison’s son to capture his father's final breath in a glass test tube. You can actually see that tube today at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

- He hated cigarettes: He published a book called The Case Against the Little White Slaver and wouldn't allow his employees to smoke, even off the clock, if he could help it.

- The Quadricycle: His first vehicle, built in a shed behind his home in 1896, was too wide to fit through the door. He had to take an axe to the brick wall to get his invention out for its first test drive.

Why the "Ford Myth" Still Matters

Henry Ford basically invented the weekend. Well, sort of. In 1926, he adopted the five-day, 40-hour workweek. Again, it wasn't just kindness. He realized that if people had more leisure time, they’d spend money—and they’d need a car to go places.

He didn't just build a product; he built a lifestyle. He popularized "vertical integration," where his company owned the iron mines, the timber forests, the glass works, and the railroads. He wanted to control every single molecule of the production process.

Modern "just-in-time" manufacturing owes a debt to Ford’s ruthlessness. But he also serves as a warning. His rigidity, his refusal to listen to his son Edsel, and his isolation in his later years nearly bankrupted the company. It took his grandson, Henry Ford II, to seize control in a corporate coup to save the brand from the old man's declining faculties.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

Studying Henry Ford isn't just for history buffs. If you're in business or just trying to navigate the world, there are some pretty heavy lessons here.

- Audit Your "Sociological" Tendencies: If you lead a team, are you valuing their work, or are you trying to control their lives? Ford’s success came from pay; his failures came from his need for total moral control.

- The Danger of the "One Way": The Model T was great until it wasn't. Always look for the "next" thing even when your current "thing" is at its peak. Don't wait for a competitor to force your hand.

- Control vs. Collaboration: Fordlandia failed because he refused to listen to local expertise. Whether you're entering a new market or starting a new hobby, don't assume your success in one area automatically makes you an expert in another.

- Acknowledge the Whole Person: It’s tempting to either idolize or demonize historical figures. Real life is messier. You can admire Ford’s engineering genius while flatly rejecting his bigotry.

If you ever find yourself in Michigan, go to Greenfield Village. It’s a 80-acre "living history" museum Ford built. He literally bought the buildings where his heroes (like the Wright Brothers and Edison) worked, took them apart brick-by-brick, and moved them there. It’s a bizarre, beautiful, and slightly haunting monument to a man who tried to freeze time while simultaneously moving the world faster than it had ever gone before.

To understand the 21st century, you really have to understand the man who broke the 19th. Ford was a genius, a tyrant, a visionary, and a bigot. He was the quintessence of the American spirit—both the parts we celebrate and the parts we’re still trying to fix.

Next Steps for Deep Exploration:

- Visit the Henry Ford Museum: If you want to see the "Last Breath" of Edison or the actual chair Lincoln was sitting in when he was shot (Ford bought that too), this is the place.

- Read "The People's Tycoon": Steven Watts provides one of the most balanced biographies that digs into Ford's psychological complexities.

- Watch "The Cars That Made America": A great visual breakdown of how the rivalry between Ford, Dodge, and Chrysler shaped the US economy.