Most people remember reading it in high school. You probably remember the green light, the yellow car, and the fact that Gatsby was kind of a stalker. But there is a reason F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Great Gatsby haven’t faded into the background of literary history like so many other "classics" from the 1920s. It isn't just about a guy trying to get a girl back. Honestly, it’s a horror story about the American Dream, written by a man who was watching his own life fall apart in real-time.

Fitzgerald wasn't writing from an ivory tower. He was in the thick of it. He was a celebrity. He and his wife, Zelda, were the "it" couple of the Jazz Age, known for jumping into fountains and spending money they didn't have. When he wrote about Gatsby's parties, he was writing about the world he saw every weekend on Long Island. He saw the rot under the glitter.

The Messy Reality Behind West Egg

The book didn't just fall out of the sky. It was born from Fitzgerald’s obsession with social standing. He was always the "poor boy in a rich man’s world." He went to Princeton but didn't graduate. He fell in love with a socialite named Ginevra King, whose father famously told him, "Poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls."

That line basically created Jay Gatsby.

When you look at F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Great Gatsby, you’re looking at a man trying to process his own rejection. He eventually married Zelda Sayre, but only after he became famous and had some money. He was constantly chasing a version of himself that was "enough" for the elite.

It’s easy to think of the 1920s as just flappers and jazz. It was more than that. It was a massive economic shift. People were getting rich off the stock market and bootlegging, and the "old money" families—the Buchanans of the world—hated it. They didn't want the new guys around. That tension is the engine of the novel. It’s a class war disguised as a romance.

Why the "Great" Gatsby Isn't Actually Great

The title is sarcastic. Most people miss that.

Gatsby is a fraud. He’s a bootlegger who changed his name and manufactured a personality. But Fitzgerald frames him as "great" because he’s the only one in the book who actually believes in something. Everyone else is cynical. Tom is a bigot. Daisy is "careless." Jordan Baker is a liar. Gatsby, for all his flaws, has an "extraordinary gift for hope."

Is it a good thing? Probably not. It’s what kills him.

🔗 Read more: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

But Fitzgerald makes us root for him anyway. We want the lie to be true. We want the green light to be reachable. That’s the trick of the prose. He uses these lush, over-the-top descriptions to mirror the way Gatsby sees the world—through a filter of gold and blue.

The Problem With Daisy Buchanan

People love to hate Daisy. They call her a villain because she chooses Tom over Gatsby in the end. But if you look at the historical context, Daisy didn't have many options.

In 1925, a woman’s social security was tied entirely to her husband. Tom was a monster, but he was a "safe" monster with a pedigree. Gatsby was a mystery. When the truth comes out in that hot hotel room in Manhattan—that Gatsby is just a criminal with a fancy library—Daisy’s world collapses. She isn't a hero, but she’s a product of her environment. She’s "the golden girl," and as Fitzgerald writes, her voice is "full of money."

That’s such a weird, specific description. It’s not a compliment.

F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Great Gatsby: The Flop That Became a Legend

Here is a wild fact: the book was a failure when it first came out.

Seriously.

When Fitzgerald died in 1940, he thought he was a washed-up alcoholic. He had copies of the second printing of Gatsby sitting in a warehouse because nobody wanted them. He died in Hollywood, trying to write movie scripts to pay the bills, convinced he’d be forgotten.

It wasn't until World War II that the book took off. The Council on Books in Wartime sent millions of "Armed Services Editions" to soldiers overseas. They were small, paperbound books designed to fit in a pocket. Soldiers in the trenches and on ships started reading about this guy in a pink suit, and suddenly, the book resonated. It wasn't about the 20s anymore; it was about the feeling of longing for a life you left behind.

💡 You might also like: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

The Narrative Voice of Nick Carraway

Nick is the sneakiest character in the book. He tells you right at the start that he’s "inclined to reserve all judgments."

He’s lying.

He judges everyone. He’s the ultimate "fly on the wall," but he’s also complicit. He sets up the meeting between Gatsby and Daisy. He watches the affair happen. He covers for them. By making Nick the narrator, Fitzgerald forces us to see the story through the eyes of someone who wants to belong but knows he doesn't.

Nick is basically us. He’s the tourist in the world of the ultra-wealthy, disgusted by their behavior but fascinated by their shine.

Symbolism That Actually Matters

We’ve all heard about the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg. The giant billboard looking over the Valley of Ashes.

It’s not just "God is watching." It’s more cynical than that. It’s a billboard for an eye doctor that has been abandoned. It’s an advertisement. In the world of F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Great Gatsby, even the "eyes of God" are just a commercial that no one bothered to take down.

Then there’s the Valley of Ashes itself. It was a real place—a dumping ground for furnace ashes in Queens (where Citi Field is now). It represents the people who get chewed up by the American Dream. While Gatsby and the Buchanans are drinking champagne, George and Myrtle Wilson are living in a literal gray wasteland.

The contrast is the point. You can't have the parties in West Egg without the trash in the Valley of Ashes.

📖 Related: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

What Most People Get Wrong About the Ending

The ending is often read as a tragedy about lost love. It’s actually a commentary on time.

"So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

That is one of the most famous lines in English literature, and it’s deeply depressing. It’s saying that we try to move forward, we try to reinvent ourselves, but we are always dragged back by where we came from. Gatsby tried to erase James Gatz, the poor kid from North Dakota, but James Gatz is the one who ended up dead in that pool.

You can’t outrun your history. No matter how much money you make.

Fitzgerald was obsessed with this idea because he felt his own youth slipping away. He was watching the "Jazz Age" turn into the Great Depression. The party was over, and the lights were being turned off.

How to Read Gatsby Today

If you want to actually "get" the book, stop looking at it as a romance. It’s a ghost story. Gatsby is a ghost of a man who died years ago in Louisville when he lost Daisy. He’s spent five years trying to haunt his own life.

To dive deeper into the world of F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Great Gatsby, here is what you should actually look into:

- Read "The Crack-Up": This is a series of essays Fitzgerald wrote later in life. It’s raw. It’s honest. It explains exactly how it felt to lose his mind and his talent. It puts the desperation of Gatsby into perspective.

- Look up the real-life "Gatsby": Max Gerlach. He was a bootlegger and a gentleman who used the phrase "Old Sport." He’s widely considered to be one of the primary inspirations for Jay Gatsby.

- Visit the Gold Coast: If you’re ever in Long Island, go to the Sands Point Preserve. That’s the real "East Egg." You can see the massive mansions that made Fitzgerald feel so small. It makes the geography of the book feel real.

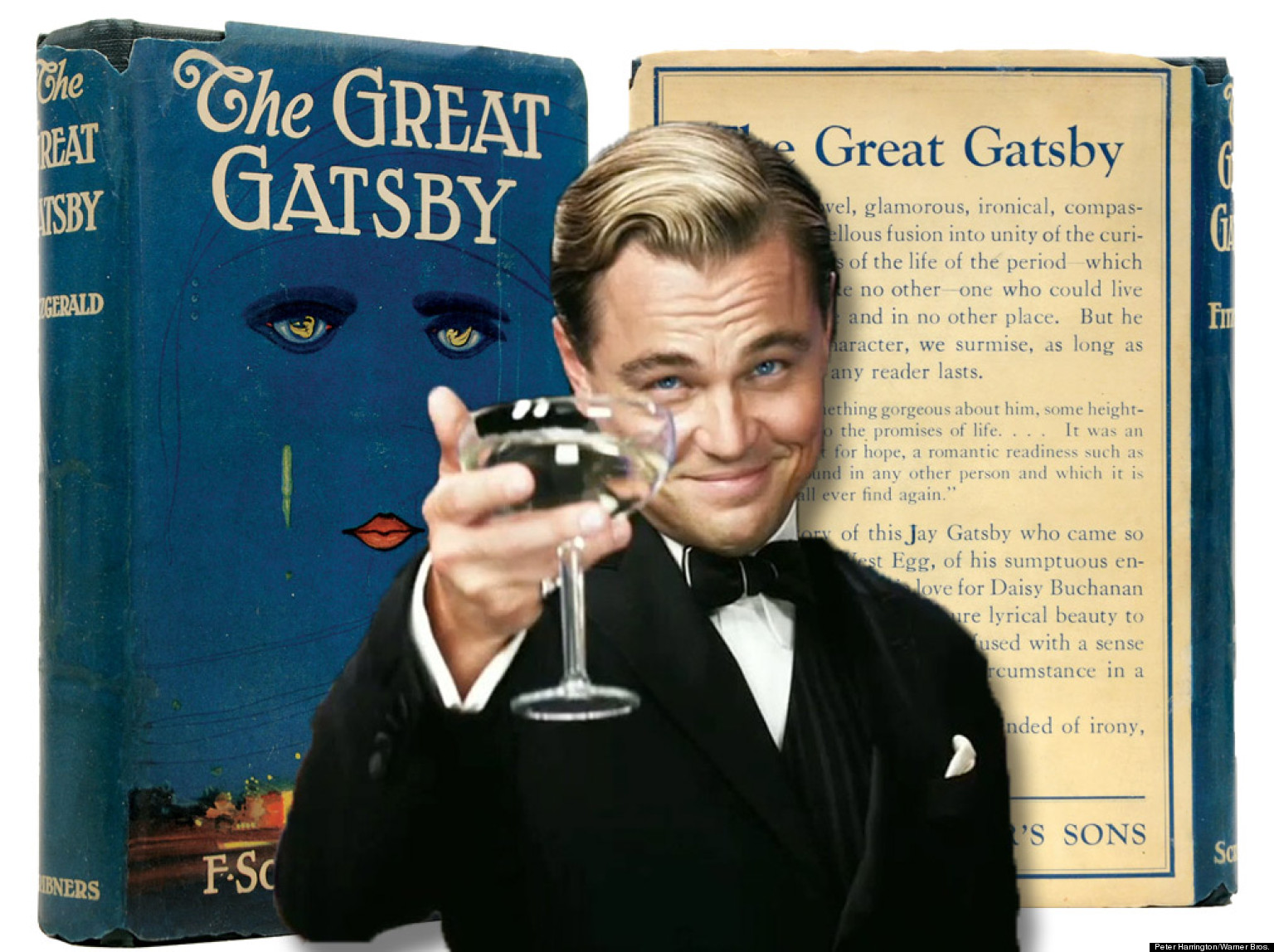

- Watch the 1974 version (not just the 2013 one): While the DiCaprio version is a visual trip, the 1974 version with Robert Redford captures the quiet, eerie stillness of the "old money" world much better.

Fitzgerald didn't write a textbook. He wrote a warning. He wanted us to see that chasing a dream that is rooted in the past is a suicide mission. We are still reading it a century later because, honestly, we haven't learned the lesson yet. We're still chasing the green light. We're still trying to reinvent ourselves. And we're still surprised when the current pulls us back.