Ever looked at a blade of grass and wondered why it doesn't look anything like a rose petal? It seems like a random quirk of nature. Honestly, it isn't. It all comes down to a split that happened millions of years ago in the evolutionary history of flowering plants, or angiosperms. If you're trying to figure out examples of monocotyledons and dicotyledons, you’re basically looking at the two main "families" of the plant world. Botanists call them monocots and dicots for short.

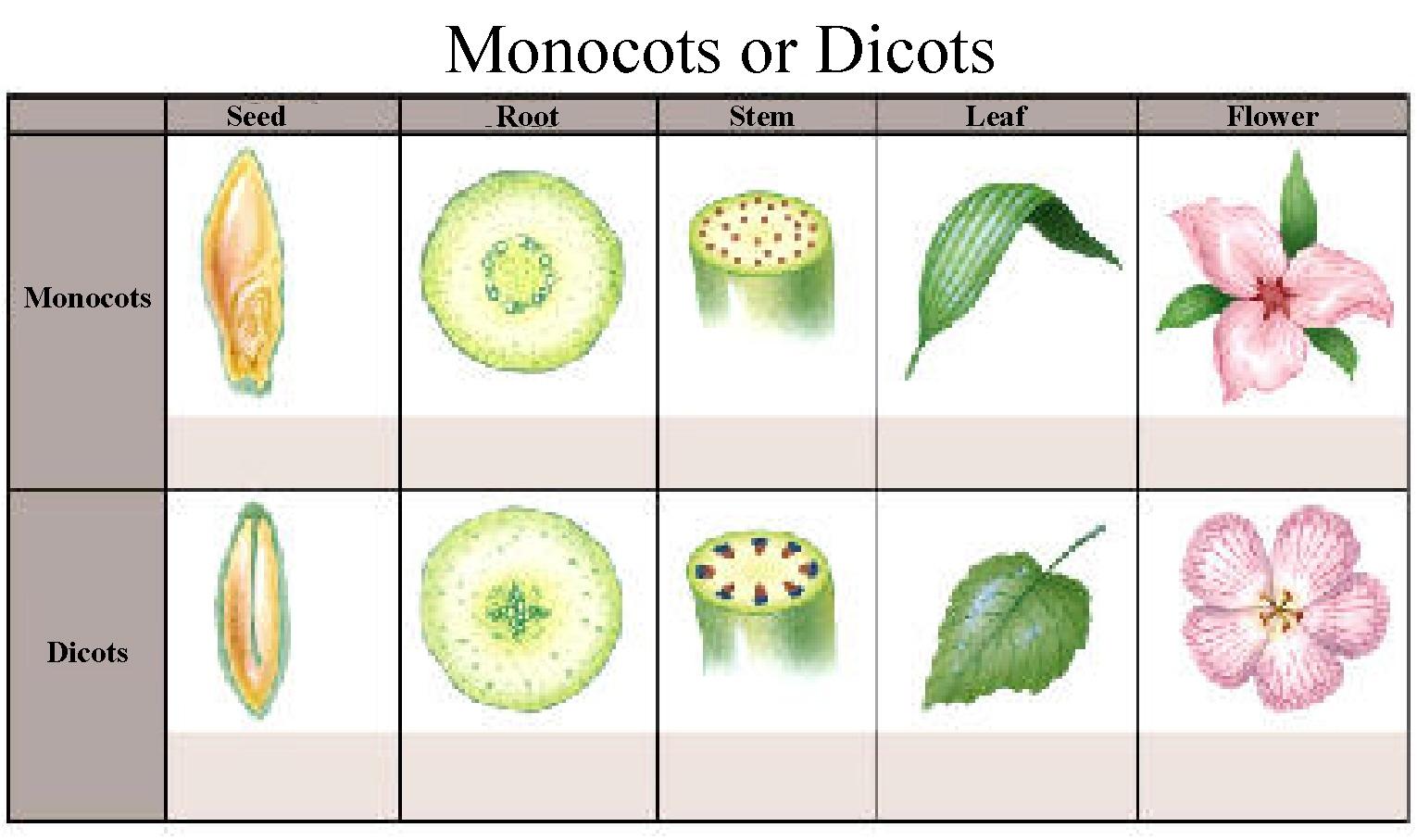

The name refers to the cotyledon. That’s the very first leaf—the "seed leaf"—that pokes out of the soil when a plant germinates. Monocots have one. Dicots have two. Simple, right? Well, sort of. While the seeds are the starting point, the differences eventually show up in the roots, the veins in the leaves, and even how many petals are on the flowers.

The Big Hitters: Common Examples of Monocotyledons

You eat monocots every day. Seriously. If you’ve had toast, a bowl of rice, or popcorn, you’ve consumed a monocot. These plants are the backbone of human civilization. Because they grow quickly and often produce high-energy seeds, we’ve relied on them for millennia.

Take Corn (Zea mays). It’s the quintessential monocot. When a corn kernel sprouts, a single green spike emerges. If you look at a corn leaf, the veins run in straight, parallel lines from the base to the tip. They don't branch out like a map of city streets; they look more like guitar strings. This parallel venation is a dead giveaway.

Then there are the Grasses. Your lawn? Monocots. Wheat, barley, oats, and sugarcane? All monocots. These plants have fibrous root systems. Instead of one big main root going deep into the earth, they have a tangled mat of thin roots that stay relatively close to the surface. It's why pulling up a clump of grass brings a huge chunk of sod with it.

Liliaceae, the lily family, gives us some of the most beautiful examples of monocotyledons. Lilies, tulips, and onions all fall into this camp. If you count the petals on a lily, you’ll usually find three, or a multiple of three. That "rule of threes" is a classic monocot trait. Orchids are another massive group here. They are actually one of the largest families of flowering plants on Earth, featuring incredibly complex flowers that, surprisingly, still follow the basic monocot blueprint.

Don't forget the Palms. This is where things get trippy. Most monocots don't grow "wood" in the way an oak tree does. They don't have a vascular cambium, which is the layer that creates rings in a tree. So, technically, a coconut palm isn't "wood" in the traditional botanical sense; it’s a massive bundle of vascular tissues. Other examples include bananas, ginger, and even asparagus.

💡 You might also like: Finding Obituaries in Kalamazoo MI: Where to Look When the News Moves Online

Moving to the Other Side: Dicotyledon Favorites

Most of the "pretty" things in a garden—the bushes, the fruit trees, the sprawling vines—are dicots. They are incredibly diverse. When you plant a bean seed in a damp paper towel (remember that second-grade science project?), it splits into two halves. Those two halves are the cotyledons.

Legumes are perhaps the most famous examples of monocotyledons and dicotyledons comparisons because they show the "two-leaf" start so clearly. Beans, peas, lentils, and peanuts are all dicots. They usually have a taproot system. Think of a carrot. That’s a massive taproot. It’s one main central pillar with smaller roots branching off it.

The Rose family (Rosaceae) is a huge deal. This doesn't just include the flowers you buy for Valentine’s Day. It includes apples, pears, strawberries, and cherries. If you look at an apple leaf, the veins aren't parallel. They look like a web or a net. This is called reticulate venation. It’s messy, branched, and efficient at moving nutrients across a wide leaf surface.

Most "hardwood" trees are dicots. Oaks, maples, and elms. Because they have that vascular cambium I mentioned earlier, they can grow wider every year, creating those concentric rings that tell you how old the tree is.

In the floral department, dicots usually have petals in multiples of four or five. Think of a Geranium or a Snapdragon. If you see a flower with five distinct petals, you’re almost certainly looking at a dicot. This group also includes "broadleaf" plants like sunflowers, tomatoes, and even cacti.

Telling Them Apart in the Wild

You don't need a microscope to tell these apart. You just need to know where to look. Honestly, once you see the patterns, you can't unsee them.

📖 Related: Finding MAC Cool Toned Lipsticks That Don’t Turn Orange on You

First, check the leaves.

Parallel lines? Monocot.

Net-like webbing? Dicot.

Next, look at the flowers.

Count the petals. If you see three, six, or nine, it’s a monocot. If you see four or five (or a lot of them, like in a rose), it’s likely a dicot.

Then, check the stems.

This is harder to see without cutting the plant, but in a monocot, the "pipes" (vascular bundles) that carry water are scattered randomly throughout the stem like polka dots. In a dicot, they are arranged in a neat, organized circle. This ring arrangement is what allows dicots to grow thick trunks.

Finally, look at the roots.

If it’s a big, singular "peg" going down, it’s a dicot. If it’s a fuzzy mess of thin hairs, it’s a monocot.

Why Does This Even Matter?

You might think this is just for people with lab coats. It isn't. If you’re a gardener or a farmer, this distinction changes how you treat your plants.

Take weed killers, for example. Many "broadleaf" herbicides are designed to kill dicots without hurting monocots. This is how you can spray a chemical on your lawn (monocot grass) and kill the dandelions (dicot) without destroying the whole yard. If you didn't know the difference, you might accidentally kill your entire garden trying to get rid of a few weeds.

👉 See also: Finding Another Word for Calamity: Why Precision Matters When Everything Goes Wrong

It also affects how you water. Monocots with fibrous roots need frequent, shallow watering because they can't reach deep into the water table. Dicots with deep taproots can often handle a bit of drought once they are established because they’re "mining" for water deep underground.

A Quick Summary of Differences

- Seeds: One cotyledon vs. two.

- Leaves: Parallel veins vs. branched/netted veins.

- Flowers: Multiples of 3 vs. multiples of 4 or 5.

- Stems: Scattered vascular bundles vs. ring-arranged bundles.

- Roots: Fibrous (shallow) vs. Taproot (deep).

Digging Deeper into Specialized Examples

Let's get specific. Orchids are some of the most specialized monocots. People often think they are dicots because they look so complex, but they are firmly in the monocot camp. Their seeds are tiny—almost like dust—and they rely on fungi in the soil to help them grow. On the flip side, something like a Sunfower (Helianthus) is a powerhouse dicot. The "flower" of a sunflower is actually hundreds of tiny individual flowers clustered together, all following the dicot rules.

In the world of food, the distinction is everywhere.

Monocot foods: Garlic, onions, ginger, bananas, pineapple, asparagus, vanilla.

Dicot foods: Potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, beans, broccoli, apples, walnuts.

Interestingly, the way these plants deal with pests differs too. Many monocots have high silica content in their leaves (think of how a blade of grass can give you a paper cut). This makes them tough for some insects to chew. Dicots often rely more on chemical warfare, producing alkaloids or tannins to taste bitter or even toxic to herbivores.

Actionable Steps for Your Own Backyard

If you want to use this knowledge, start by auditing your own space. It’s a great way to understand the biology of what you’re growing.

- Check your weeds. Pull one up. Does it have a long central root (taproot)? If so, it's a dicot. If it breaks off and leaves a bunch of thin hair-like roots in the ground, it's a monocot. This tells you how much of the "root ball" you need to remove to stop it from coming back.

- Identify your "power plants." If you're growing grain or corn, remember they need nitrogen differently than your beans (dicots). Legumes actually "fix" nitrogen into the soil, while monocot grasses tend to gulp it up.

- Pruning strategy. Be careful pruning monocots like palms or dracaenas. Unlike dicots, they often have a single growing point at the top. If you cut the "head" off a palm, it won't grow back like a hedge (dicot) would. It will simply die.

Understanding the split between monocotyledons and dicotyledons isn't just about passing a biology quiz. It’s about recognizing the fundamental structures that dictate how the green world functions around you. Next time you're at the grocery store or walking through a park, try to spot the "rule of three" or the "parallel veins." You'll start seeing the logic in the landscape almost immediately.