Nature is weird. Honestly, if you look closely at how things live, you’ll realize that "survival of the fittest" isn't just about who has the biggest muscles or the sharpest teeth. It’s about who has the best hacks. We see examples of adaptations in animals every single day, but we usually overlook them because they’re just so good at what they do.

Evolution doesn't care about being flashy. It cares about what works.

If a frog needs to freeze solid to survive the winter, it does. If a bird needs to pretend it’s a venomous snake to keep from being eaten, it’ll do that too. These aren't just cool party tricks. They are high-stakes biological gambles that have paid off over millions of years. When we talk about adaptation, we’re talking about the difference between a species thriving and a species becoming a fossil.

The Absolute Weirdness of Physical Changes

Structural adaptations are the things you can actually see. It's the physical hardware. Think of it like the body kit on a car, but instead of looking cool at a stoplight, it's keeping the engine from exploding in the desert heat.

Take the Fennec fox. You’ve seen them—the tiny desert foxes with ears that look like they're trying to pick up satellite signals from Mars. Those ears aren't just for hearing prey scuttling under the sand, though they’re great for that. They’re basically giant radiators. Blood vessels in the ears are positioned close to the skin, allowing body heat to escape into the air. In the Sahara, where temperatures can hit $50°C$ ($122°F$), that's a literal lifesaver. Without those oversized ears, the fox would basically cook from the inside out.

Polar Bears and the Black Skin Secret

Most people think polar bears are white. They aren't. Their fur is actually translucent and hollow, which reflects light to make them look white so they can sneak up on seals. But underneath all that fluff? Their skin is jet black.

This is a classic example of an adaptation that serves a dual purpose. The black skin absorbs every bit of UV radiation from the sun that makes it through the fur. If they had pink skin like a domestic pig, they’d lose heat way too fast. It's a specialized thermal system. Plus, their paws have these tiny bumps called papillae that act like natural snow tires, providing grip on the ice so they don't slide around like a cartoon character.

💡 You might also like: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

Behavioral Adaptations Are Just Smart Business

Sometimes the body doesn't change, but the "software" does.

Behavioral adaptations are the things animals do to stay alive. It’s often more about timing and social cues than it is about physical traits.

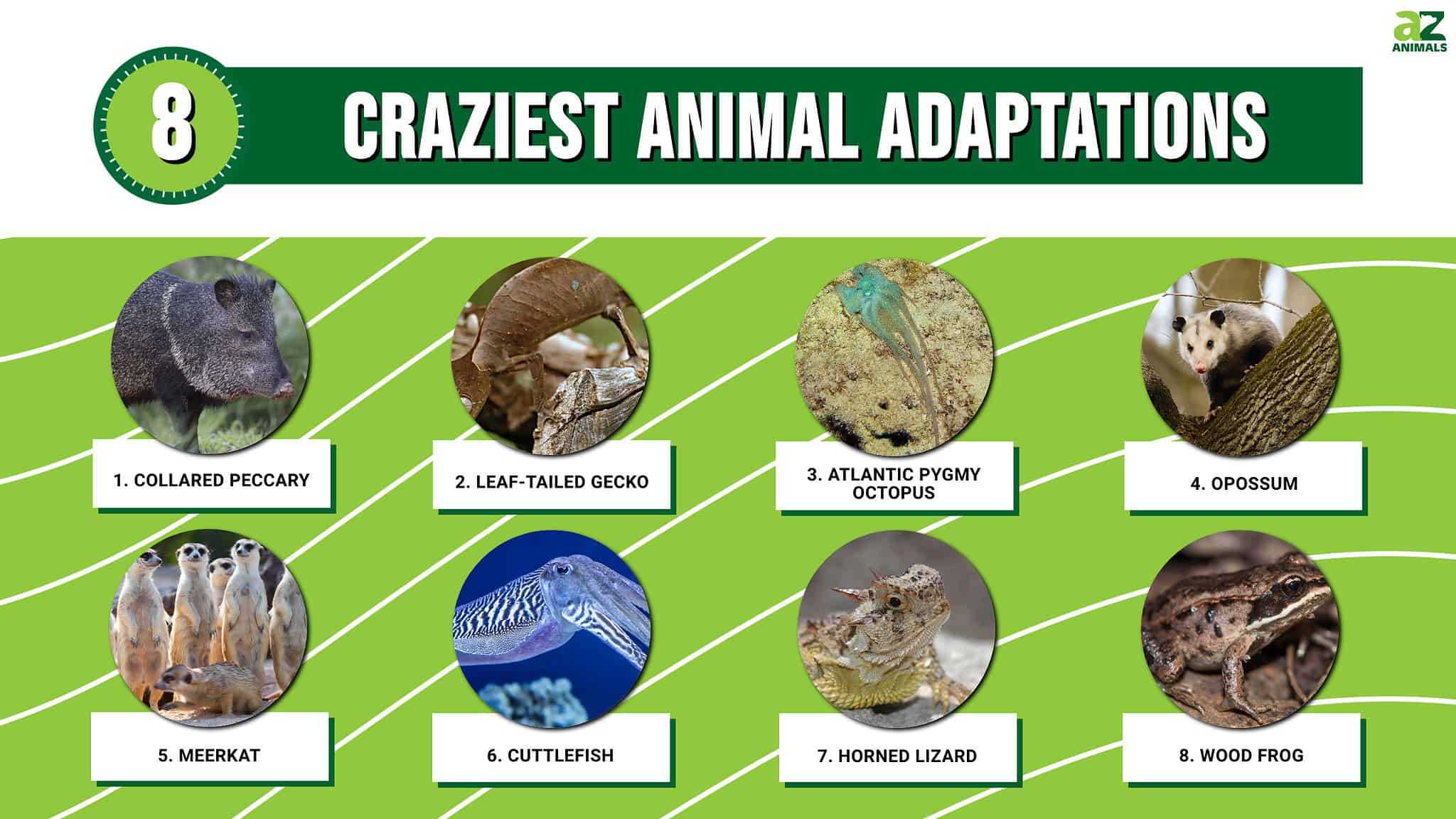

The Opossum is the king of this. Everyone knows "playing possum," but it’s actually way more intense than just lying down. When an opossum is threatened, it goes into an involuntary state of tonic immobility. It’s not "pretending." Its heart rate drops, and it actually releases a foul-smelling fluid from its anal glands that makes it smell like rotting meat. Most predators want a fresh kill, not a stinky, dead-looking pile of fur. It’s a gross, brilliant, and highly effective way to be left alone.

Bird Migration: The Original GPS

Think about the Arctic Tern. This bird flies from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back every single year. That’s about 44,000 miles. Why? Because it wants to live in a world of perpetual summer where food is always blooming.

They don't have Google Maps. They use a mix of the Earth's magnetic field, the position of the sun, and even chemical cues in the air to find their way. This behavior is hard-wired. If they stayed in one place, they’d starve. By moving, they exploit the best resources the planet has to offer at exactly the right time.

Physiological Adaptations: The Internal Lab

This is where things get really sci-fi. Physiological adaptations happen inside the body, usually at a chemical or cellular level. You can’t see them, but they’re probably the most impressive examples of adaptations in animals because they defy what we think is possible for living tissue.

📖 Related: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

The Wood Frog is a master of this.

During Alaskan winters, these frogs literally freeze. Their heart stops. Their breathing stops. They become a "frog-sicle." Usually, when cells freeze, the water inside them expands and shreds the cell walls, which is why frostbite is so dangerous for humans. But the Wood Frog floods its blood with glucose (sugar) and urea. This acts like a natural antifreeze. The water between the cells freezes, but the cells themselves stay hydrated and intact. When spring hits, the frog thaws out and just hops away like nothing happened.

Deep Sea Pressure Cookers

Down in the Mariana Trench, the pressure is roughly 1,000 times higher than at sea level. If you put a regular fish down there, it would be crushed instantly.

Animals like the Snailfish have evolved to have bones that aren't fully calcified—they’re more like cartilage. Their cell membranes are also specifically designed to stay fluid under intense pressure. They’ve basically rebuilt their entire molecular structure to survive in a place that would turn a human into a pancake.

Mimicry: The Art of the Lie

Survival isn't always about being the strongest. Sometimes it’s about being the best liar.

The Mimic Octopus is the ultimate shapeshifter. It doesn’t just change color to blend into the background. It actually changes its shape and movement to look like other, more dangerous animals. If it sees a predatory damselfish, it might tuck six of its legs away and pretend to be a venomous sea snake. If it’s out in the open, it might flatten itself and swim like a toxic flatfish.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

It’s assessing the threat and choosing the specific lie that will work best in that moment. That's high-level cognitive adaptation disguised as a physical one.

The Misconception of "Perfect" Adaptation

People often think evolution is moving toward some "perfect" version of an animal. It's not.

Adaptation is messy. It’s about what’s "good enough" to survive until reproduction. Sometimes, an adaptation that helped a million years ago becomes a burden. The Giant Irish Elk grew antlers so large (up to 12 feet across) to attract mates that it likely struggled to move through dense forests when the climate shifted. Evolution doesn't have a plan. It’s just a series of reactions to a changing world.

Biologist Stephen Jay Gould often talked about "spandrels"—traits that exist not because they are adaptations themselves, but as byproducts of other changes. Not everything has a "reason." But the things that do have a reason are usually pretty spectacular.

What You Can Do With This Knowledge

Understanding how animals adapt isn't just for trivia night. It’s a blueprint for how we solve human problems.

- Look into Biomimicry: Engineers are constantly looking at animal adaptations to solve human problems. The Shinkansen bullet train in Japan was redesigned based on the beak of a Kingfisher to reduce noise and increase speed. If you're in a creative or technical field, look at how nature solves "friction"—it’s usually already figured out the most efficient way.

- Support Habitat Preservation: The biggest threat to these adaptations is the speed of human-driven climate change. Animals can adapt to almost anything over thousands of years, but they can't adapt to a 5-degree temperature shift in fifty years. Supporting organizations like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) or local conservation trusts helps maintain the environments these specialists need.

- Observe Locally: You don't need to go to the Amazon to see this. Look at the birds in your backyard. Notice how their beak shapes differ based on what they eat. The "cracking" beak of a finch is a world away from the "tweezer" beak of a warbler.

- Think About Your Own Adaptations: Humans adapt too, though usually through culture and technology. We didn't grow fur; we made coats. We didn't grow gills; we made scuba gear. Recognizing our place in this biological continuum helps us understand our impact on the planet.

Evolution is an ongoing process. Right now, in cities across the world, moths are becoming darker to blend in with soot, and birds are singing at higher pitches to be heard over traffic. The story of adaptation isn't over; it's just getting a new chapter.