Space is big. Really big. You might think it's a long way down the road to the chemist, but that's just peanuts to space. Douglas Adams said it best, but even he struggled to quantify the sheer, mind-numbing emptiness between stars. When we ask how far is one light year, we aren't just talking about a long road trip. We are talking about a distance so vast that our brains literally aren't wired to visualize it properly.

Basically, a light year is how far a beam of light travels in a single Earth year. Light is the fastest thing in the universe. It moves at about 186,282 miles per second. If you could travel that fast, you'd circle the Earth seven and a half times in the blink of an eye. Now, imagine doing that every second, for 365 days straight. That's the distance we’re trying to wrap our heads around. It’s not a measurement of time, even though the word "year" is right there in the name. It's a ruler. A really, really long one.

The Math Behind the Madness

To get the actual number, you just do some basic multiplication. Take the speed of light, multiply it by 60 seconds, then 60 minutes, then 24 hours, and finally 365.25 days (gotta count that leap year wiggle room). The result? Roughly 5.88 trillion miles. Or, if you prefer the metric system like most scientists, it's about 9.46 trillion kilometers.

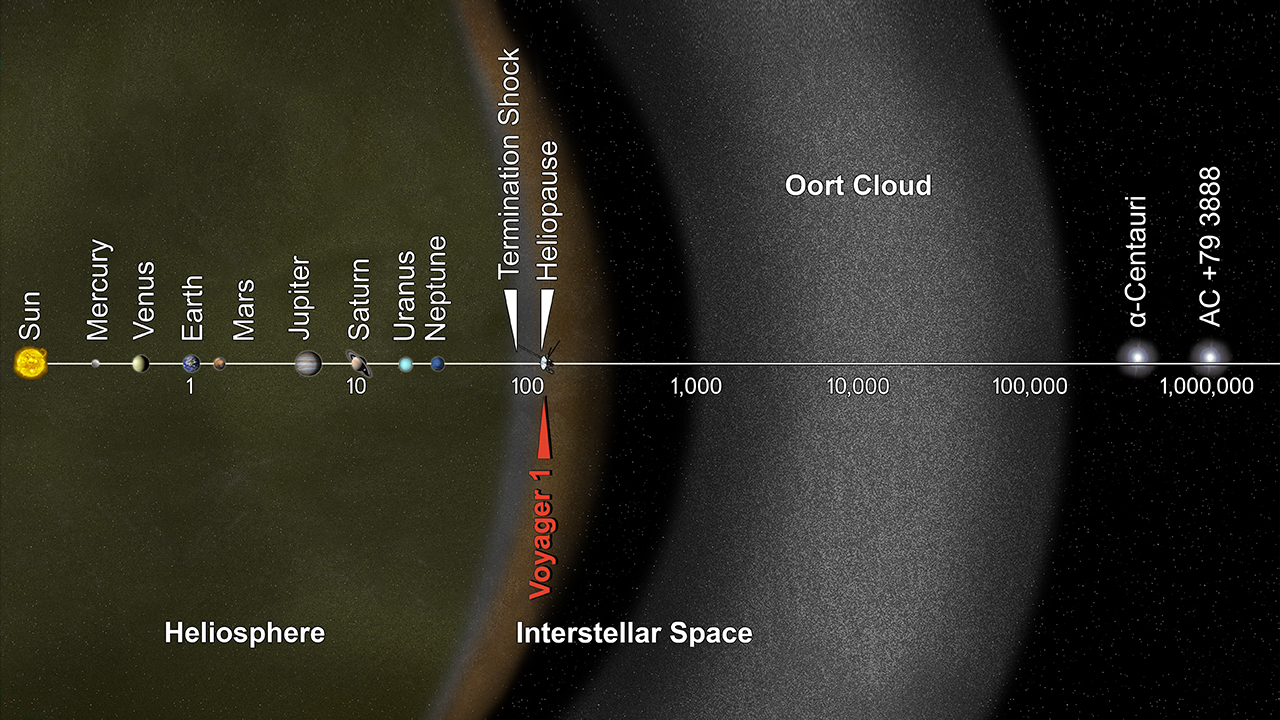

Numbers that big tend to lose their meaning. We see "trillion" and our eyes glaze over. To put it in perspective, if you were to drive a car at a steady 60 miles per hour, it would take you about 11 million years to cover the distance of one light year. You’d need a lot of snacks. Even the Voyager 1 spacecraft, which is currently screaming away from us at 38,000 miles per hour, would take somewhere around 17,000 to 18,000 years to cross just one light year of space.

Why We Don't Use Miles in Space

Using miles to measure the galaxy is like trying to measure the distance from New York to Tokyo in microns. The numbers just get too clunky. Astronomers use light years because it makes the math manageable when talking about the neighborhood.

Take Proxima Centauri, our closest stellar neighbor. It’s about 4.25 light years away. That sounds close, right? "Oh, it's just four units away." But if you convert that to miles, you’re looking at roughly 25 trillion miles. If NASA released a press release saying "We found a planet 25,000,000,000,000 miles away," it doesn't quite have the same ring to it. Plus, light years give us an accidental bonus: they tell us how old the light is that we're seeing.

Looking Back in Time

This is the part that usually trips people up. Because light takes time to travel, looking into deep space is exactly like using a time machine. When you look at Proxima Centauri through a telescope, you aren't seeing it as it exists right now, this second. You're seeing the light that left that star over four years ago.

If Proxima Centauri suddenly exploded today, we wouldn't know about it until 2030. We are literally seeing the past. The further out we look, the further back in time we go. The Andromeda Galaxy is about 2.5 million light years away. That means the light hitting your eyes from Andromeda tonight started its journey before Homo sapiens even existed. That's heavy.

👉 See also: Getting a Sharp ISS Pic From Earth Is Harder Than You Think

Common Misconceptions About Space Distances

People often confuse light years with "parsecs." You can thank Han Solo for some of that confusion. A parsec is actually a larger unit—about 3.26 light years. It's based on trigonometry and the way stars seem to shift against the background as Earth moves around the sun (parallax). Scientists often prefer parsecs for technical papers, but the light year remains the king of public science communication because it's so intuitive. Well, as intuitive as a trillion-mile ruler can be.

Another common mistake is thinking the solar system is light years wide. It isn't. Not even close. To measure things within our own sun's influence, we use "Astronomical Units" or AU. One AU is the distance from the Earth to the Sun (about 93 million miles).

- The Sun is 8 light-minutes away.

- Pluto is only about 0.0006 light years away.

- The Oort Cloud, the very edge of our solar system's gravitational reach, is maybe 1.5 to 2 light years thick, but the planets are all huddled much closer.

The Practical Reality of Crossing a Light Year

Kinda makes you realize how stuck we are. With current chemical rocket technology—the stuff we used for Artemis or the Space Shuttle—we aren't going anywhere fast. To actually cover one light year in a human lifetime, we’d need a complete revolution in propulsion technology.

There are serious people working on this, though. Projects like Breakthrough Starshot are looking at using powerful lasers to push tiny "nanocrafts" with light sails. The goal is to get these chips up to 20% of the speed of light. At that speed, they could reach Proxima Centauri in about 20 years. Still, that's just a tiny probe. Sending a human? That’s a whole different level of engineering nightmare involving radiation shielding, life support, and the fact that hitting a grain of space dust at 20% light speed would be like a nuclear bomb going off.

Scaling the Universe

If we want to understand the scale of the Milky Way, we have to scale up from that one light year. Our galaxy is about 100,000 light years across.

🔗 Read more: Java 25 Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Latest Version

Think about that.

If you were a photon of light, it would take you a hundred thousand years just to cross from one side of our "city" to the other. And the Milky Way is just one of billions of galaxies. The observable universe is estimated to be about 93 billion light years in diameter. The reason that number is bigger than the age of the universe (13.8 billion years) is because space itself is expanding, stretching the distance between things while the light is still in transit. It's weird, it's confusing, and it makes you feel very small.

Actionable Insights for the Amateur Stargazer

Understanding how far is one light year changes how you look at the night sky. It's no longer a flat curtain of lights; it's a 3D environment with depth. Here is how you can use this knowledge next time you're outside:

👉 See also: Buying an SDXC Card for MacBook Pro: Why Most People Overpay for the Wrong Speed

- Find Sirius: It’s the brightest star in the sky. It’s about 8.6 light years away. When you look at it, realize that the light entering your eye left Sirius when a movie from nearly a decade ago was just hitting theaters.

- Locate the Big Dipper: The stars in this constellation look like they belong together, but they are at vastly different distances. Some are 60 light years away, others are over 100. They have no physical relationship to each other; they just happen to line up from our specific porch in the galaxy.

- Download a Scale App: Use an app like "Luminos" or "SkySafari." They allow you to toggle distances. Seeing the "depth" in light years helps visualize the "void" between the dots.

- Think in "Light-Time": Stop thinking of space in miles. Start thinking of it in time. The moon is 1.3 light-seconds away. Mars is roughly 12.5 light-minutes away (on average). It helps conceptualize the communication lag that future Mars colonies will deal with.

Space isn't just a place; it's a history book. Every time we measure a light year, we aren't just measuring how far away something is—we are measuring how far back in time we are allowed to see. It’s a limit imposed by the physics of our universe, a cosmic speed limit that keeps the stars isolated but also preserves their history for us to discover.

Next time you look up, remember that the distance you're seeing isn't just empty space. It's a 5.88-trillion-mile stretch of nothingness that defines the scale of our existence.

Next Steps for Exploration

To truly grasp the scale of the cosmos, your next step should be researching the Cosmic Distance Ladder. This is the succession of methods by which astronomers determine the distances to celestial objects, starting with basic geometry for nearby stars and moving to "standard candles" like Cepheid variables and Type Ia supernovae for distant galaxies. Understanding this ladder explains how we actually know these distances without ever having to leave our own backyard.