You’re probably writing Python classes every day. You define a class, you create an instance, and you move on with your life. But have you ever stopped to ask what exactly makes the class itself? Most developers treat classes like blueprints. That’s fine for 90% of work. However, when you dig into the plumbing, you realize that in Python, classes aren't just blueprints—they are live objects. And every object needs a creator. This is where meta class in python enters the chat, usually accompanied by a headache and a sense of "wait, why am I doing this?"

Python is weirdly consistent. Everything is an object. Your integers are objects. Your strings are objects. Even your functions are objects. If a class is an object, it must be an instance of something else. That "something else" is the metaclass. By default, that creator is type. If you’ve ever called type(my_object) and saw <class 'type'> returned for a class definition, you’ve seen the face of the creator. But you aren't stuck with the default. You can hijack the creation process.

👉 See also: Objeto volador no identificado: Por qué ahora hasta el Pentágono les llama de otra forma

The Secret Life of the Type Object

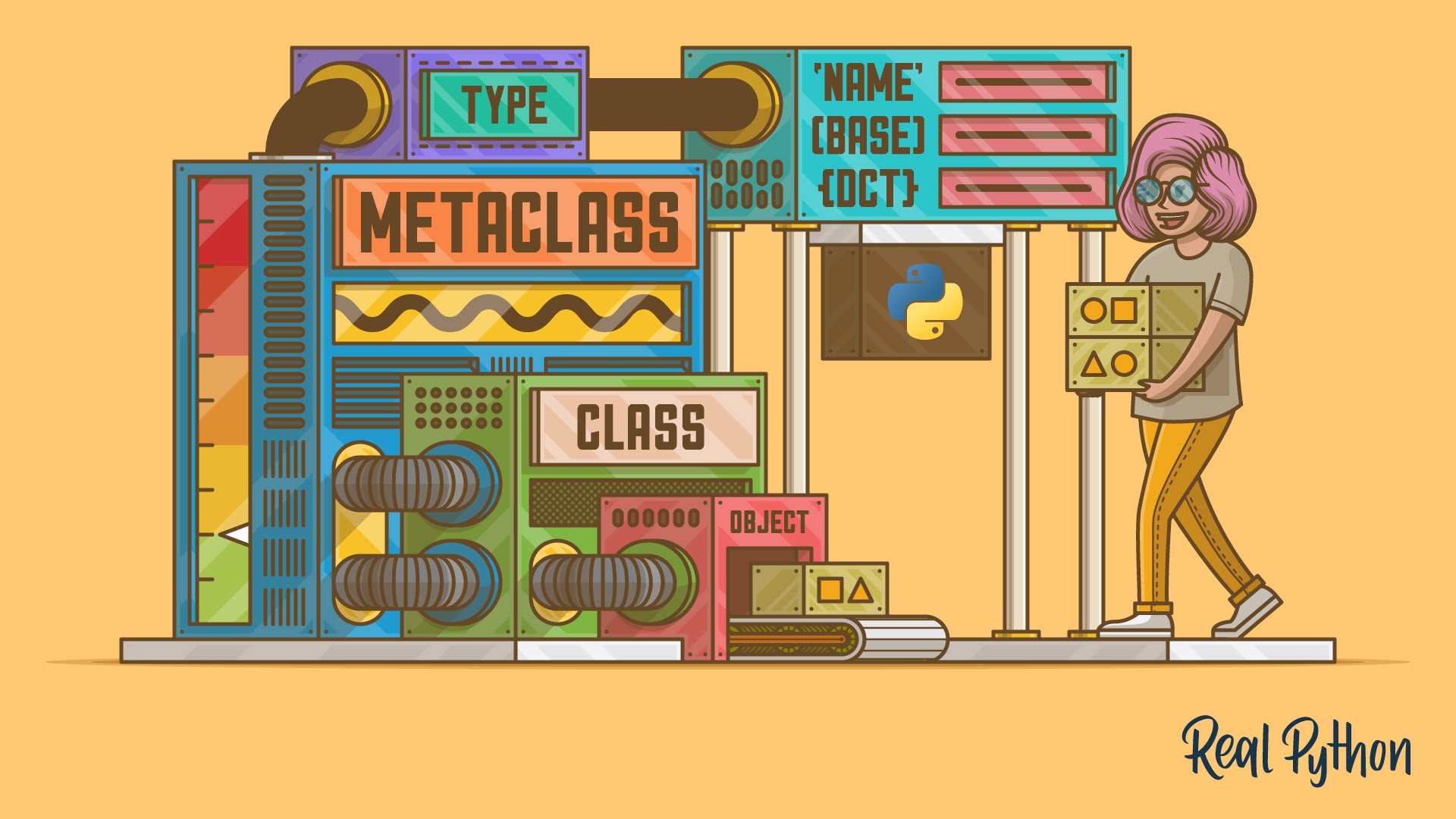

Let's be real: the name type is confusing as hell. It’s a function that tells you what an object is, but it’s also a class that builds other classes. It’s basically the "God Object" of the Python universe. When you write class MyClass: pass, Python doesn't just magically make that exist. Under the hood, it calls type('MyClass', (), {}).

It takes the name of the class, the parent classes it inherits from, and a dictionary of its attributes. Boom. You have a class.

But why should you care? Because sometimes you want your classes to behave in ways that standard inheritance won't allow. Think about Django’s Models or SQLAlchemy’s declarative base. When you define a class in Django, you just list some class variables like name = models.CharField(). Yet, somehow, when you instantiate that class, it suddenly knows how to talk to a database, validate fields, and handle complex logic. That isn’t magic. It’s a meta class in python intercepting the class creation and rewriting it on the fly.

When to Actually Use a Metaclass

Tim Peters, the guy who wrote the Zen of Python, famously said that metaclasses are "deeper magic than 99% of users should ever worry about." He was right. If you’re asking if you need one, you probably don't. You can usually get away with class decorators or simple inheritance.

However, metaclasses are the right tool when you need to enforce rules across an entire codebase without the developer even knowing it. Imagine you’re working on a massive enterprise system. You want to ensure that every single class created by your team follows a specific naming convention or has a specific attribute, and you want it to fail at import time, not runtime. A metaclass can literally refuse to let a class be created if it doesn't meet your criteria.

An Illustrative Example: Enforcing Case Sensitivity

Let’s say you’re a bit of a stickler for rules. You want to make sure no one on your team ever defines a class attribute that isn't lowercase.

class EnforceLowercase(type):

def __new__(cls, name, bases, dct):

for attr in dct:

if not attr.startswith('__') and any(c.isupper() for c in attr):

raise TypeError(f"Hey! Attribute '{attr}' in '{name}' has uppercase letters. Not on my watch.")

return super().__new__(cls, name, bases, dct)

class MyStrictClass(metaclass=EnforceLowercase):

valid_variable = 10 # This works fine

BadVariable = 20 # This will raise a TypeError immediately

Notice that __new__ method. In a metaclass, __new__ is where the action happens. It’s called before the class is even born. You get to look at the name, the bases, and the dictionary of attributes (the dct) and mess with them. You can add methods, delete variables, or throw an error like I did above. It’s pure power.

The call Method and Singleton Patterns

One of the most common "real world" uses for a meta class in python—even if it’s a bit controversial—is implementing the Singleton pattern. A Singleton ensures that a class only ever has one instance.

Normally, when you call MyClass(), you’re invoking the __call__ method of the class's metaclass. By overriding __call__ in your own metaclass, you can control whether a new object is actually created or if you just return an existing one.

class Singleton(type):

_instances = {}

def __call__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if cls not in cls._instances:

cls._instances[cls] = super().__call__(*args, **kwargs)

return cls._instances[cls]

class DatabaseConnection(metaclass=Singleton):

def __init__(self):

print("Connecting to the database...")

If you call DatabaseConnection() five times, you only see that print statement once. The metaclass is acting as a gatekeeper. Honestly, it’s a lot cleaner than hacking it inside the class itself using __new__.

Why You Might Want to Avoid Them

Look, metaclasses make code harder to read. If a junior developer jumps into your repo and sees a custom metaclass, their brain might melt. It adds a layer of "invisible" logic that doesn't show up in the class definition.

In modern Python (3.6+), we got __init_subclass__. It’s a much simpler way to do about 80% of what people used to use metaclasses for. If you just need to register a subclass or set some default values when a class is inherited, use __init_subclass__. It’s more readable and less likely to break your IDE’s autocomplete.

The Architecture of Class Creation

To truly master the meta class in python, you have to understand the sequence. It’s not just a random pile of methods. When Python sees a class definition:

- It determines the proper metaclass (it looks at the

metaclass=keyword, then the bases, then the global scope). - It prepares the namespace by calling the metaclass's

__prepare__method. This is cool because it lets you use things likeOrderedDictfor the class dictionary (though in Python 3.7+, dicts are ordered by default anyway). - It executes the class body in that namespace.

- It calls the metaclass's

__new__to create the class object. - It calls the metaclass's

__init__to initialize the class object.

It’s a factory. A literal factory for building objects that then build other objects. If that sounds meta, well, that's why they call it that.

Nuance: Abstract Base Classes

Actually, you’ve probably used metaclasses without realizing it if you've ever used the abc module. abc.ABCMeta is the metaclass that makes abstract base classes work. It’s what prevents you from instantiating a class that hasn't implemented all its abstract methods. It hooks into the creation process to verify that the "contract" is fulfilled.

Moving Forward with Metaprogramming

So, what should you actually do with this information? Don't go out and rewrite your entire codebase with metaclasses tomorrow. You’ll regret it. Instead, start by looking at your current class hierarchies. Are you repeating the same boilerplate over and over? Are you manually registering classes in a central registry?

Actionable Next Steps:

🔗 Read more: Why the Large Round Bottom Flask Still Runs the Modern Laboratory

- Audit your Boilerplate: Check if you have complex logic inside

__init__that actually belongs to the class structure itself. If so, see if__init_subclass__can simplify it. - Experiment in Isolation: Create a small script using a metaclass to see if you can auto-generate docstrings or validate method signatures across a family of classes.

- Read Library Source Code: Open up the source for a library like

PydanticorMarshmallow. They use metaclasses (or similar machinery) to transform simple class attributes into powerful data validators. It’s the best way to see how the pros handle this "magic." - Check Compatibility: Remember that metaclasses can be tricky with multiple inheritance. If two parent classes have different metaclasses, Python will throw a

TypeError(metaclass conflict). Be ready to write a "common" metaclass if you hit this wall.

Metaprogramming is a tool for library authors and framework designers. For the rest of us, it’s a fascinating look under the hood that explains why Python is as flexible as it is. Use it sparingly, but keep it in your back pocket for those moments when inheritance just isn't enough.