It was late summer, 1974. A dusty, sun-scorched plateau in Twin Falls, Idaho, had basically become the center of the universe. Or at least, the center of a very weird, very rowdy universe. Robert "Evel" Knievel—a man who lived his life in a red-white-and-blue leather jumpsuit—was about to do the unthinkable. He wasn't just jumping a few Greyhound buses this time. He was going to fly over the Evel Knievel Snake River Canyon jump site in a steam-powered rocket.

Honestly, calling it a "motorcycle jump" is a bit of a stretch. The machine, dubbed the Skycycle X-2, looked more like a giant silver bullet with wheels than anything you'd see on a highway. It was a 13-foot-long pressure cooker on wings. The plan? Blast across a 1,600-foot gap over a canyon floor dropping 500 feet straight down.

People expected a miracle. What they got was a riot, a mechanical "fizzle," and one of the most debated moments in the history of extreme sports.

The Skycycle X-2: A Steam-Powered Pipe Dream?

Before the jump, Knievel had already become a living legend for breaking bones. He’d smashed his back, his pelvis, and pretty much every limb at least once. But the Snake River Canyon was different. The government wouldn't let him jump the Grand Canyon, so he leased a patch of private land in Idaho and hired a former Navy engineer named Robert Truax to build him a ride.

Truax wasn't some backyard tinkerer; he was a serious rocket scientist. But the Skycycle X-2 was an odd beast. It used superheated water—literally steam—to generate 6,000 pounds of thrust. There was no internal combustion engine. Just a tank of water heated to $600^\circ\text{F}$ ($315^\circ\text{C}$). When Knievel hit the button, a "cork" would pop, and the steam would propel him up a massive dirt ramp at 350 mph.

It sounded brilliant. On paper.

In reality, the tests were a disaster. The first unmanned prototype went straight into the river. The second one fared just as poorly. Knievel's team was terrified. They begged him to do one more test, but the money was running out and the hype was already at a boiling point. Evel, being Evel, decided to "wing it." He famously said that he wasn't afraid of dying, but he was afraid of being "stale."

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Woodstock Without the Love: The Twin Falls Chaos

If you weren't there, it's hard to describe the vibe at the canyon that week. Imagine about 30,000 people—bikers, hippies, families, and thrill-seekers—crammed into a temporary city in the middle of nowhere. There were no hotels. People just slept in the dirt.

It was absolute mayhem.

Reports from the time describe a "happening" that turned dark. There was plenty of beer, plenty of drugs, and a lot of boredom. When the beer ran out, things got ugly. Some of the "Hell’s Angels" were reportedly hired as security, which went about as well as you’d expect. They ended up clashing with the crowds. There was nudity, vandalism, and a general sense that the whole thing might implode before the rocket even launched.

Reporters on the scene, like Tim Woodward from the Idaho Statesman, mentioned moving backwards from the canyon rim because the crowd was pushing so hard. People were literally on the edge of terror. They didn't just want to see a jump; they wanted to see something—anything—happen.

What Happened During the Evel Knievel Snake River Canyon Jump

September 8, 1974. The sun was high. Knievel climbed into the cramped cockpit. He looked like an astronaut from a low-budget sci-fi movie. The crane lowered him onto the ramp. The countdown started.

Three. Two. One.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

A massive roar of white steam erupted. The Skycycle X-2 shot up the ramp like a bat out of hell. For about two seconds, it looked like he might actually make it. But then, tragedy (or comedy, depending on who you ask) struck.

The drogue parachute deployed almost immediately.

As the rocket cleared the ramp, the white chute blossomed behind it, acting like a giant brake. Instead of soaring across the 1,600-foot gap, the Skycycle stalled in mid-air. It began to float, then tumble, down into the gorge. The wind—which is always tricky in a canyon—actually saved Knievel’s life. It blew the rocket backward toward the launch wall.

If it had fallen straight down or moved forward, Evel would have landed in the Snake River. Here’s the scary part: Knievel was strapped into the seat with a harness he couldn't release himself. He would have drowned in his own rocket. Instead, he slammed into the rocks on the canyon floor, just feet away from the water's edge.

The Aftermath and the "Rip-Off" Accusations

Knievel survived with nothing more than a broken nose and some scrapes. For a guy who had survived the Caesar's Palace crash, this was a walk in the park. But the fans? They weren't happy.

Many felt cheated. They had paid good money—some watching on closed-circuit TV in theaters across the country—to see a man fly. Instead, they saw a parachute malfunction. A "dud."

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

There were rumors for years that Evel "pulled the cord" himself because he lost his nerve. Engineers later debunked this, blaming a design flaw in the parachute's mechanical cover. It basically couldn't handle the "base drag" of the launch. Still, the damage to Knievel’s reputation was real. Some called it the "Snake River Rip-off."

Why the Jump Still Matters Today

Despite the failure, the Evel Knievel Snake River Canyon jump is the DNA of modern extreme sports. Before the X Games, before Red Bull Stratos, there was a guy in a leather suit trying to jump a canyon in a steam rocket.

It proved that there was a massive market for "spectacle." People would pay to see someone try the impossible, even if they failed miserably. It was the birth of the modern "daredevil" as a brand.

In 2016, a stuntman named Eddie Braun actually finished what Knievel started. He built a replica rocket (the "Evel Spirit") with the help of Scott Truax—the son of the original designer. He hit the button, the chute stayed in, and he soared across the canyon successfully. He proved the math was right all along. Evel just had bad luck—or a bad latch.

What You Should Do If You Visit Twin Falls

If you’re a fan of history or just want to see where it all went down, you can still visit the site today. Here is how to make the most of it:

- See the Ramp: The massive dirt berm used for the launch is still visible on the south rim of the canyon. It’s about two miles east of the Twin Falls Visitor Center.

- Walk the Trail: The Centennial Trail is a paved path that gets you within about 100 yards of the jump site. It’s a bit of a hike, but it gives you a terrifying perspective of just how wide that gap really is.

- Visit the Monument: There’s a monument dedicated to Knievel near the Perrine Bridge. It’s a great spot for a photo and a quick history lesson.

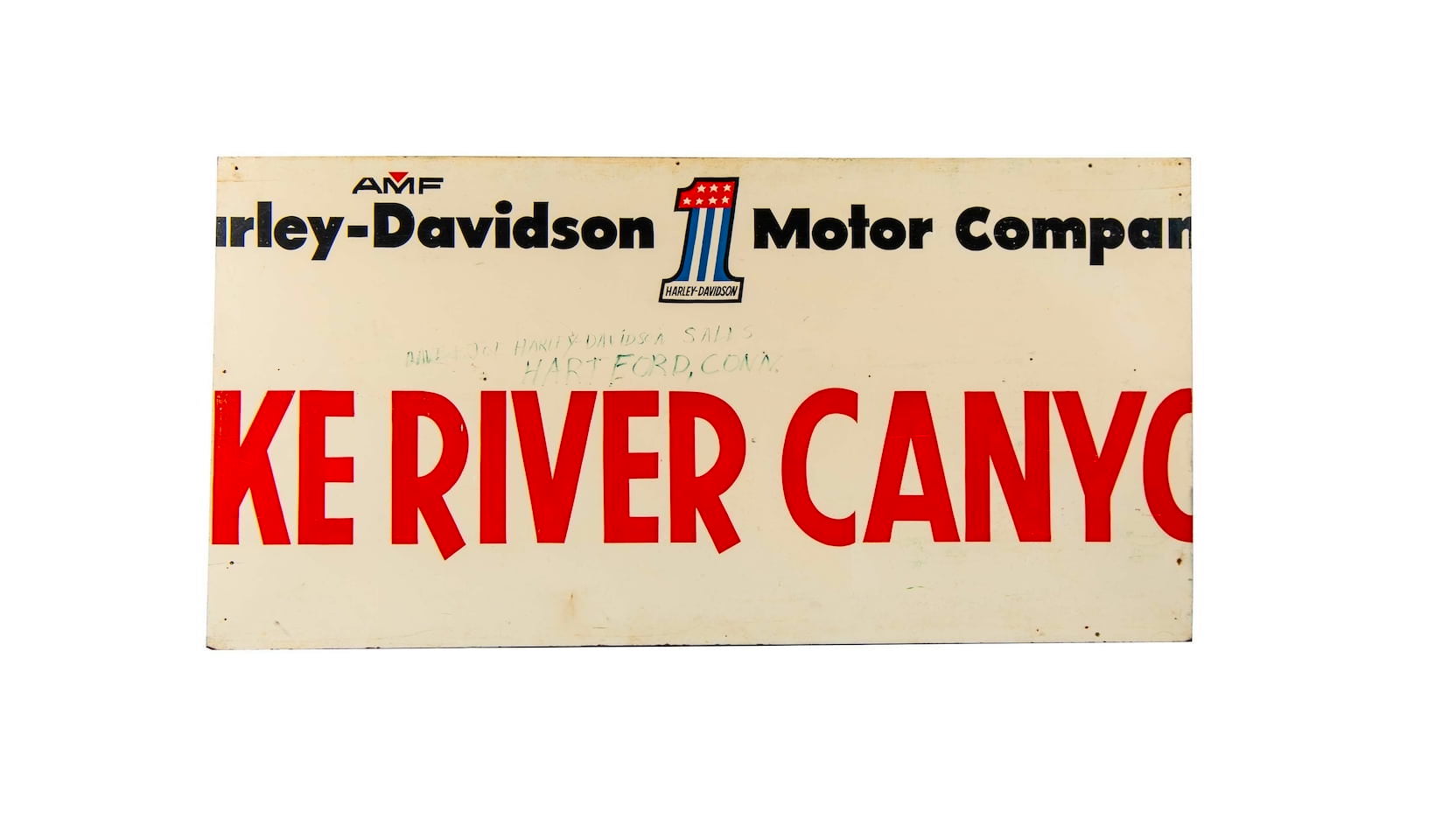

- Check out the Museum: If you want to see the actual "leftovers," the Skycycle X-2 (the one used for the jump) is often on display at the Evel Knievel Museum or at various Harley-Davidson exhibits. Seeing it in person makes you realize how crazy he truly was to climb inside.

To understand the jump, you have to understand the era. It wasn't about the landing; it was about the audacity of the launch. Knievel didn't make it to the other side, but he made sure nobody ever forgot he tried.

Next time you're driving through Southern Idaho, pull over near the Perrine Bridge. Look at that 500-foot drop. Imagine a man in a white jumpsuit, strapped to a tank of boiling water, looking at that same view and saying, "Yeah, I can clear that." That's the real legacy of the Snake River Canyon.

Instead of just reading about the history, you should take a look at the modern footage of Eddie Braun's successful recreation to see how the physics were actually supposed to work. It puts the entire 1974 "failure" into a much clearer perspective.