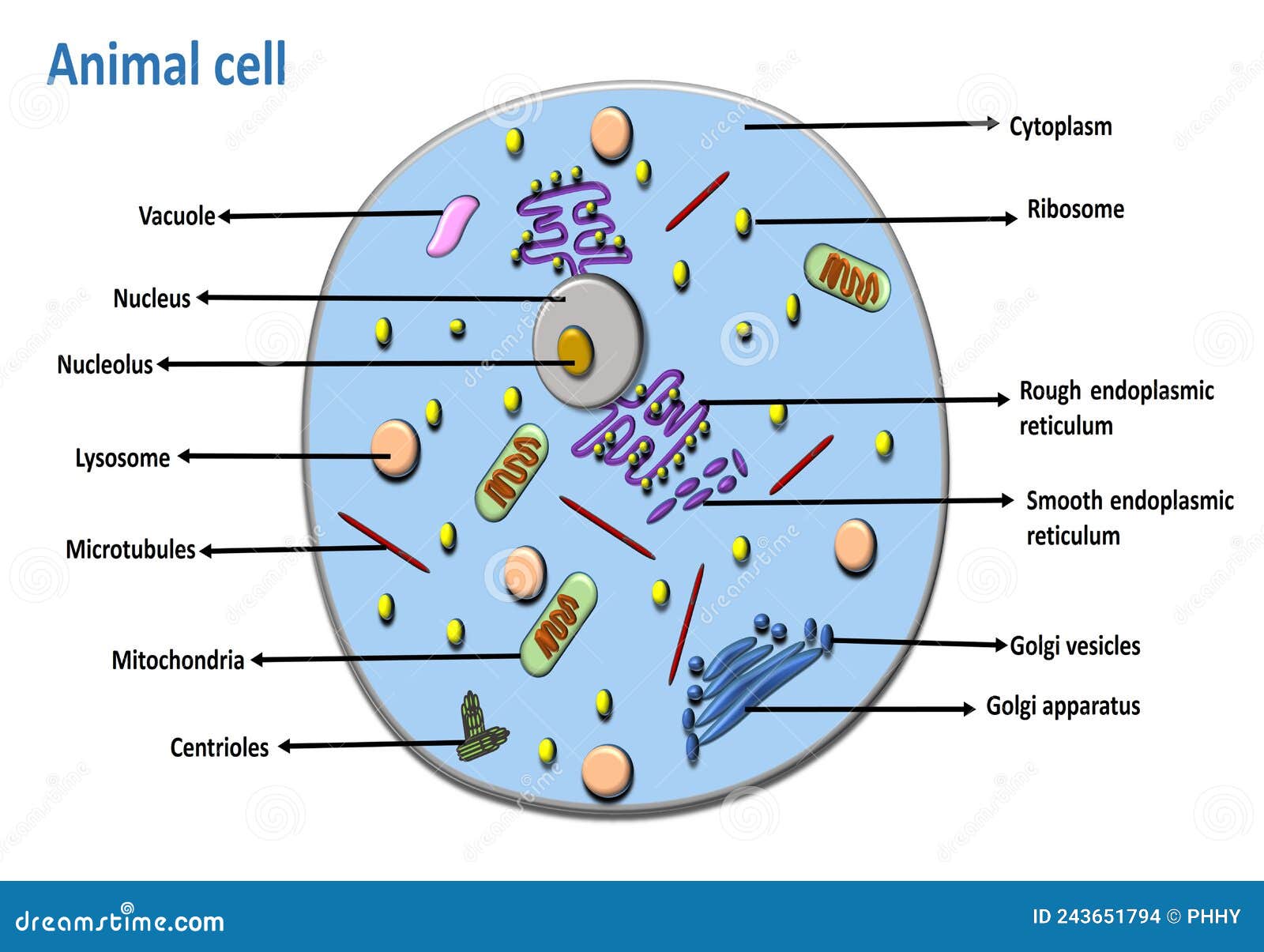

You've seen it a thousand times. That colorful, bean-shaped blob in your high school biology book with the little squiggles inside. It looks like a cross-section of a very busy jelly bean. Most people look at a eukaryotic cell labeled diagram and think, "Okay, there’s the nucleus, there’s the powerhouse, I’m done."

But honestly? That static image is kind of a lie.

Cells aren't static. They are violent, crowded, pulsating chemical factories. If you could actually shrink down and stand inside a human liver cell, you wouldn't see a tidy map. You’d see a chaotic storm of proteins hitting each other at hundreds of miles per hour. It’s crowded in there. It’s messy. Understanding the diagram is just the first step toward realizing how incredibly weird you actually are on a microscopic level.

The Nucleus Is Not Just a "Brain"

We always call the nucleus the "brain" of the cell. That’s a bit of a lazy metaphor, isn't it? If we’re being real, it’s more like a highly secured, master library that’s constantly being raided for blueprints.

Inside that double-membraned vault, your DNA isn't just floating around like spaghetti in a bowl. It’s packed. It’s coiled around proteins called histones so tightly that it’s a miracle the cell can even read the instructions. When you look at a eukaryotic cell labeled diagram, you’ll see the nucleolus sitting right in the middle. That’s not just a "center." It’s a factory for ribosomes. It’s arguably the most active spot in the entire cell.

Think about the nuclear pores. They aren't just holes. They are sophisticated gatekeepers. They decide what gets to talk to the DNA and what doesn’t. If a virus wants to hijack you, it has to find a way to trick these pores. It’s high-stakes security.

The Endomembrane System: The Cell's Logistics Nightmare

The space between the nucleus and the outer edge of the cell is where the real work happens. This is the cytoplasm, but it’s mostly filled with the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) and the Golgi Apparatus.

Most diagrams show the ER as a series of flat pancakes. In reality, it’s a massive, winding labyrinth. The "Rough" ER is covered in ribosomes, making it look like it’s been rolled in sand. This is where proteins are born. But here’s what the diagrams don’t show: folding. If a protein folds wrong, the cell has to destroy it. If it doesn't, you get diseases like Alzheimer’s or Cystic Fibrosis.

Then there’s the Golgi. It’s basically the FedEx hub. It takes those proteins, slaps a "shipping label" (usually a sugar molecule) on them, and sends them off in vesicles.

📖 Related: What Does Kinesiology Tape Do? The Science Behind the Colorful Strips on Pro Athletes

- Vesicles are the delivery trucks.

- Lysosomes are the trash compactors, filled with acid to dissolve waste.

- Peroxisomes handle the toxic stuff, like breaking down alcohol in your liver.

Mitochondria: More Than Just a Powerhouse Meme

We have to talk about the mitochondria. It’s the one thing everyone remembers. $ATP$ production happens here through the citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain. But there is a secret history here that most people forget.

Mitochondria were once independent bacteria.

Billions of years ago, one cell ate another, but instead of digesting it, they formed a pact. This is called endosymbiosis. This is why mitochondria have their own DNA. They have their own ribosomes. They even divide on their own schedule. When you look at a eukaryotic cell labeled diagram, you’re looking at two different organisms that decided to live together forever. That’s not just biology; that’s a billion-year-old roommate agreement that actually worked.

The Cytoskeleton: The Invisible Scaffolding

If you took all the organelles out of a cell, it wouldn't just be a bag of water. It would hold its shape. Why? Because of the cytoskeleton.

This is the part most students skip, but it’s arguably the coolest. It’s made of microtubules, intermediate filaments, and microfilaments. It’s not just a skeleton; it’s a railway system. Motor proteins like kinesin literally "walk" along these tubes, carrying huge cargo bags (vesicles) to different parts of the cell. It looks like a tiny, two-legged robot dragging a trash bag behind it.

What You Won't Find in Plant Cells (And Vice Versa)

It’s a common mistake to think all eukaryotes are the same. They aren't. If you’re looking at a diagram of a plant cell, you’re going to see three big differences:

- The Cell Wall: A rigid outer layer made of cellulose. It’s why trees stand up without bones.

- Chloroplasts: The green machines that turn sunlight into sugar. Like mitochondria, these also have their own DNA and an endosymbiotic past.

- The Large Central Vacuole: This is a giant water balloon in the middle of the cell. It provides "turgor pressure." When you forget to water your plants and they wilt, it’s because this vacuole has deflated.

Animal cells, on the other hand, have centrioles. These look like little bundles of pasta and are vital for cell division. Most plants don't have them.

Why This Matters for Modern Medicine

Understanding a eukaryotic cell labeled diagram isn't just for passing a test. It’s how we cure people.

Take cancer. Cancer is essentially a cell’s regulatory system failing. The "checkpoints" in the cell cycle—often managed by proteins created in the ER and sorted in the Golgi—simply stop working. Or look at mRNA vaccines. To make them work, scientists had to figure out exactly how to get a piece of genetic code through the cell membrane and into the ribosomes without the lysosomes eating it first.

We are also learning that the "junk" DNA inside the nucleus isn't junk at all. It’s a complex regulatory network. We used to think 98% of our genome was useless because it didn't code for proteins. We were wrong. It's the "dark matter" of the cell, controlling when and how the other genes turn on.

The Membrane: The Fluid Mosaic

The outer boundary, the plasma membrane, is often drawn as a solid line. It’s actually more like a sea of oil. It’s a phospholipid bilayer. The "heads" love water; the "tails" hate it. This creates a natural barrier that keeps the insides in and the outsides out.

👉 See also: Why Tanning Bed With Red Light Therapy Is Taking Over Local Salons

Floating in this oil are proteins. Some are channels. Some are receptors. Some are anchors. This is why we call it the "Fluid Mosaic Model." It’s constantly shifting. If it gets too cold, the membrane gets brittle. If it gets too hot, it falls apart. Your body spends a massive amount of energy just keeping this delicate balance.

Breaking Down the Misconceptions

People often think the cytoplasm is just empty space. In reality, it’s so packed with proteins and molecules that it has the consistency of a thick gel or even a soft solid. Movement isn't easy. Everything is a struggle of diffusion and active transport.

Another big myth? That the diagram is a "typical" cell. There is no such thing. A neuron looks like a tree with long branches. A muscle cell has multiple nuclei and is packed with contractile fibers. A red blood cell doesn't even have a nucleus! The "standard" diagram is just a composite—a "greatest hits" of organelles.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Cell Biology

If you are trying to actually learn this stuff—whether for a premed course or just because you’re curious—don't just stare at a static image. Use these strategies to make the information stick.

- Draw it from memory, but change the perspective. Don't just draw the "side view." Try to imagine what the cell looks like from the "top" or as if you were standing on the surface of the nucleus looking out.

- Focus on the "Why" of the shape. Why are the mitochondrial membranes folded (cristae)? Because it increases surface area. More surface area means more room for the proteins that make energy. Form always follows function.

- Use 3D Models. Use interactive tools or even physical models. Seeing the spatial relationship between the ER and the Golgi makes the "logistics" metaphor much easier to understand.

- Trace a Protein's Journey. Start at a gene in the nucleus. Trace it to a ribosome, then through the ER, into a vesicle, through the Golgi, and finally out through the plasma membrane. If you can map that journey, you understand the cell.

- Compare and Contrast. Don't just study the animal cell. Look at a fungal cell or a protist. Seeing how they differ (like the chitin in fungal cell walls) highlights why the standard eukaryotic structures are so efficient.

The next time you see a eukaryotic cell labeled diagram, remember that you aren't looking at a map of a place. You’re looking at a snapshot of a high-speed, microscopic city that is currently performing trillions of chemical reactions every second just so you can sit there and read this.