You're sitting in a boardroom. Or maybe you're just trying to convince your partner that buying a $3,000 espresso machine is a "long-term investment." Either way, you're using tools that were sharpened about 2,300 years ago by a guy in a toga who didn't even have a LinkedIn profile. Aristotle basically wrote the playbook on how to change someone's mind. He called it the "modes of persuasion." Today, we know them as ethos, pathos, and logos.

But here's the thing. Most people treat these like a checklist. They think if they just mention a statistic (logos), show a picture of a sad puppy (pathos), and mention they have a PhD (ethos), the audience will just melt.

It doesn't work like that. Not in 2026, and certainly not when people have "BS detectors" tuned to a high frequency.

The Credibility Trap: Why Ethos Is More Than a Resume

Ethos is about character. It’s the "why should I listen to you?" factor. People often mistake this for just listing credentials. Look, having a degree from Stanford is great. It helps. But ethos is actually more about phronesis (practical wisdom), arete (virtue), and eunoia (goodwill toward the audience).

If I’m an expert mechanic but I’m clearly trying to rip you off, my ethos is zero. You trust my skill, but not my intent. In a business setting, your ethos is established long before you open your mouth. It's your reputation. It's the fact that you didn't ghost your last client when things got messy.

Aristotle argued in On Rhetoric that ethos is actually the most potent form of persuasion. Why? Because if the audience doesn't trust the speaker, the most logical argument in the world won't land. Think about it. If someone you despise tells you the sky is blue, you’ll probably look out the window just to double-check.

Building Ethos from Scratch

You don't need a Nobel Prize to have ethos. You just need to show you’ve done the work. Use "we" instead of "I." Admit a small mistake early on to show you're honest. This is what rhetoricians call "tactical flawing." It makes you human.

Pathos Isn't Just Making People Cry

We need to talk about pathos because it gets a bad rap. People think it’s manipulative. They think it’s about "tugging at heartstrings" in a cheap way.

Pathos is simply the emotional state of the audience. Are they angry? Bored? Terrified of losing their jobs? If you ignore the emotional context of the room, your logos—your logic—is basically dead on arrival.

Consider a CEO announcing a merger. If she focuses entirely on "synergistic efficiencies" (logos) while the employees are scared of layoffs, she has failed at pathos. She hasn't met them where they are. Effective pathos is about empathy. It’s about signaling that you feel what they feel.

I remember watching a pitch where the founder spent ten minutes on data. It was flawless data. But the investors were leaning back, arms crossed. Then, he told a story about his grandfather’s struggle with the very problem the company was solving. The energy shifted. That’s pathos. It’s the "bridge" that allows the logic to cross over into the listener’s brain.

The Dark Side of Emotion

You have to be careful. If you lean too hard into pathos without enough logos to back it up, you look like a demagogue. Or a scammer. People might feel inspired in the moment, but ten minutes later, they’ll feel "slimed." They’ll realize they were moved by a performance, not a reality.

The Logic of Logos: Data Is Not a Shield

Logos is the argument itself. The "meat."

Most people think logos means "more charts." Honestly, that’s usually a mistake. Too much data leads to "analysis paralysis." Logos is really about the enthymeme—a fancy word for a syllogism where one part is implied.

- Example: "We should invest in solar because it saves money in the long run."

- The hidden premise: We want to save money.

If your audience doesn't agree with the hidden premise, your logos fails.

In a business context, logos needs to be "pointy." It shouldn't be a dull wall of numbers. It should be a clear line from Point A to Point B. If we do X, then Y will happen. If you can't explain your logic to a ten-year-old, you probably don't understand your own logos well enough yet.

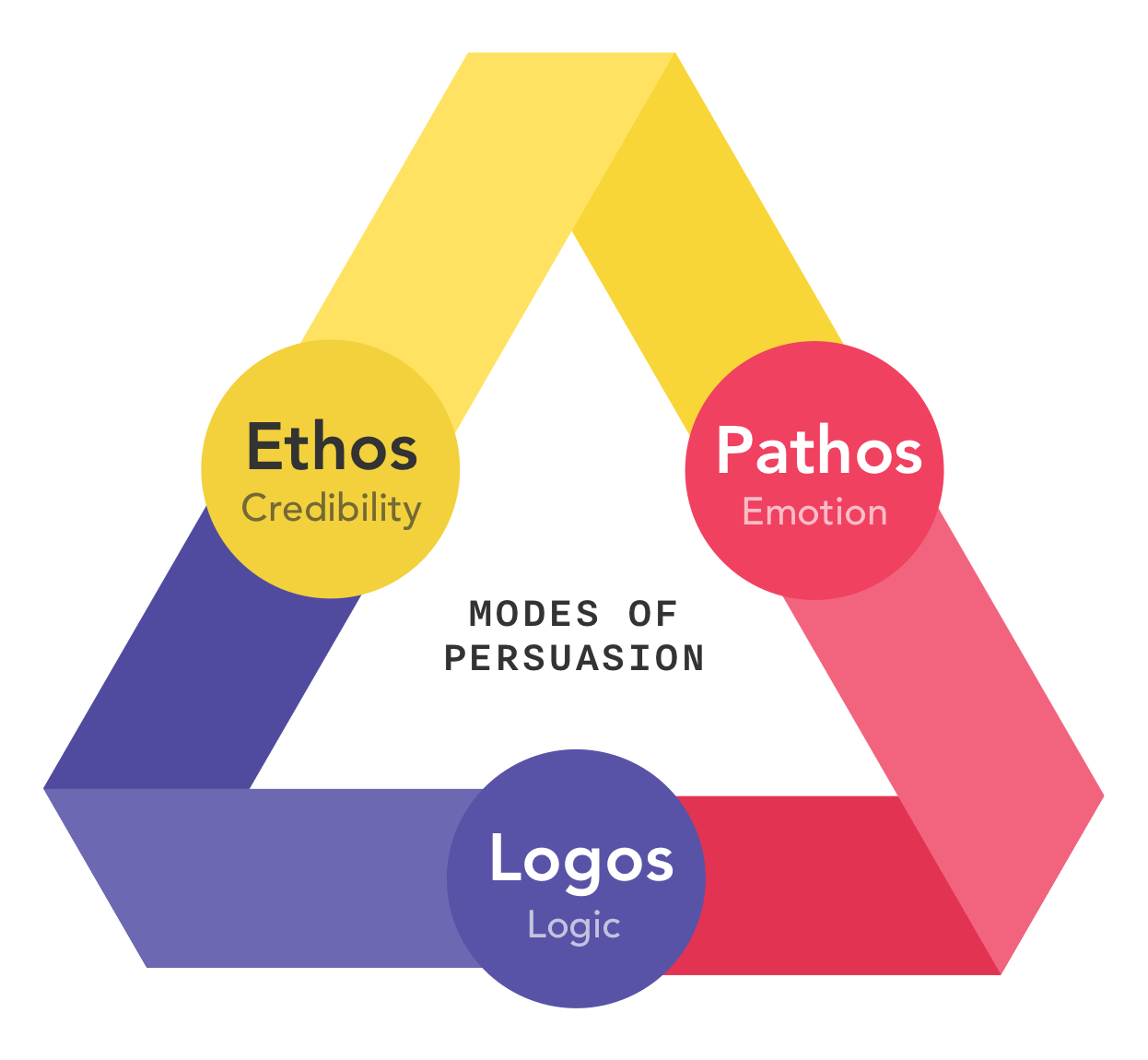

How the Three Interact (The Rhetorical Triangle)

Imagine a stool with three legs: ethos, pathos, and logos.

If one leg is shorter than the others, the whole thing topples. You’ve seen this. You’ve seen the "Expert" (Ethos) who is incredibly boring (No Pathos) and uses circular reasoning (No Logos). You’ve seen the "Hustler" (Pathos) who has no idea what they’re talking about (No Logos) and a shady background (No Ethos).

The magic happens in the overlap.

- Ethos + Logos: You sound smart and credible, but you're probably cold. People will agree with you but won't act.

- Pathos + Logos: You have a great case and it’s moving, but people don't know if they can trust you specifically to deliver.

- Ethos + Pathos: People love you and feel the vibe, but they have no idea what the plan actually is.

Real-World Case: Steve Jobs and the iPhone Launch

In 2007, Steve Jobs gave what many consider the greatest keynote of all time. He used all three perfectly.

🔗 Read more: 1 aus dollar to inr: Why the Rate is Moving So Fast Right Now

His Ethos: He was Steve Jobs. He’d already changed the world with the Mac and the iPod. He stood there in his black turtleneck—a uniform of "I’m too busy changing the world to pick out a shirt."

His Logos: He explained that current smartphones weren't smart and weren't easy to use. He showed a 2x2 matrix. He walked the audience through the logical necessity of a touch interface without a stylus. It made sense.

His Pathos: He joked. He teased. He created a sense of wonder. He made the audience feel like they were part of a "revolution." He used words like "magical."

He didn't just give a tech spec. He gave a performance that satisfied the brain, the heart, and the gut.

Why You’re Failing at Persuasion

Usually, when a pitch or an article fails, it’s because the writer is obsessed with their own perspective. You’re focused on your ethos. Your logic.

Persuasion is an act of service.

You are trying to lead someone to a conclusion that benefits them. If you’re just trying to "win," people can smell it. That’s why the Greeks emphasized Kairos—the sense of timing. You have to know when to use which tool. You don't lead with a joke at a funeral, and you don't lead with a 50-page spreadsheet at a pep rally.

Practical Steps to Mastering the Modes

Don't overcomplicate this. Next time you have to write an email, a deck, or a speech, run it through this filter.

First, check your Ethos. Do you sound like you know what you’re talking about? If not, cite a source or share a personal experience that proves you've "been there." Don't brag—just establish the ground you're standing on.

Second, look at your Logos. Is there a "therefore" in your argument? If you're just listing facts, you're not persuading; you're just talking. Every piece of data should serve a conclusion.

Third, evaluate the Pathos. What is the "temperature" of your audience? If they are stressed, your tone should be calm and reassuring. If they are complacent, your tone should be urgent. Match the emotion to the desired action.

The "So What?" Test

Read your argument back. After every sentence, ask "So what?"

- "Our software has 256-bit encryption." (Logos)

- So what?

- "So your customer data is safe." (Pathos - relief of anxiety)

- So what?

- "So you won't end up on the front page of the New York Times for a data breach." (Ethos - protecting your reputation)

Now you’re actually persuading. You've moved from a technical spec to a human reality.

Persuasion isn't about being "smooth." It's about being prepared. If you ignore the balance of ethos, pathos, and logos, you're just making noise. If you balance them, you're making a difference.

Start by identifying which of the three you naturally lean on too much. Most "left-brained" people lean on logos. Most "creatives" lean on pathos. Correct your lean, and you'll find people start saying "yes" a lot more often.