Most people hear the words Escherichia coli bacterial infection and immediately think of a bad burger or a recall on romaine lettuce. It’s the classic "stomach bug" villain. But honestly? That is such a tiny sliver of the actual story. E. coli isn't just one thing. It is a massive, diverse family of bacteria, and most of them are actually chilling in your gut right now, helping you digest dinner and producing Vitamin K. They're roommates. Usually, they're the good kind of roommates who pay rent on time and don't make noise.

The problem starts when you meet the "cousins" from out of town—the pathogenic strains that have evolved specific ways to hijack your system.

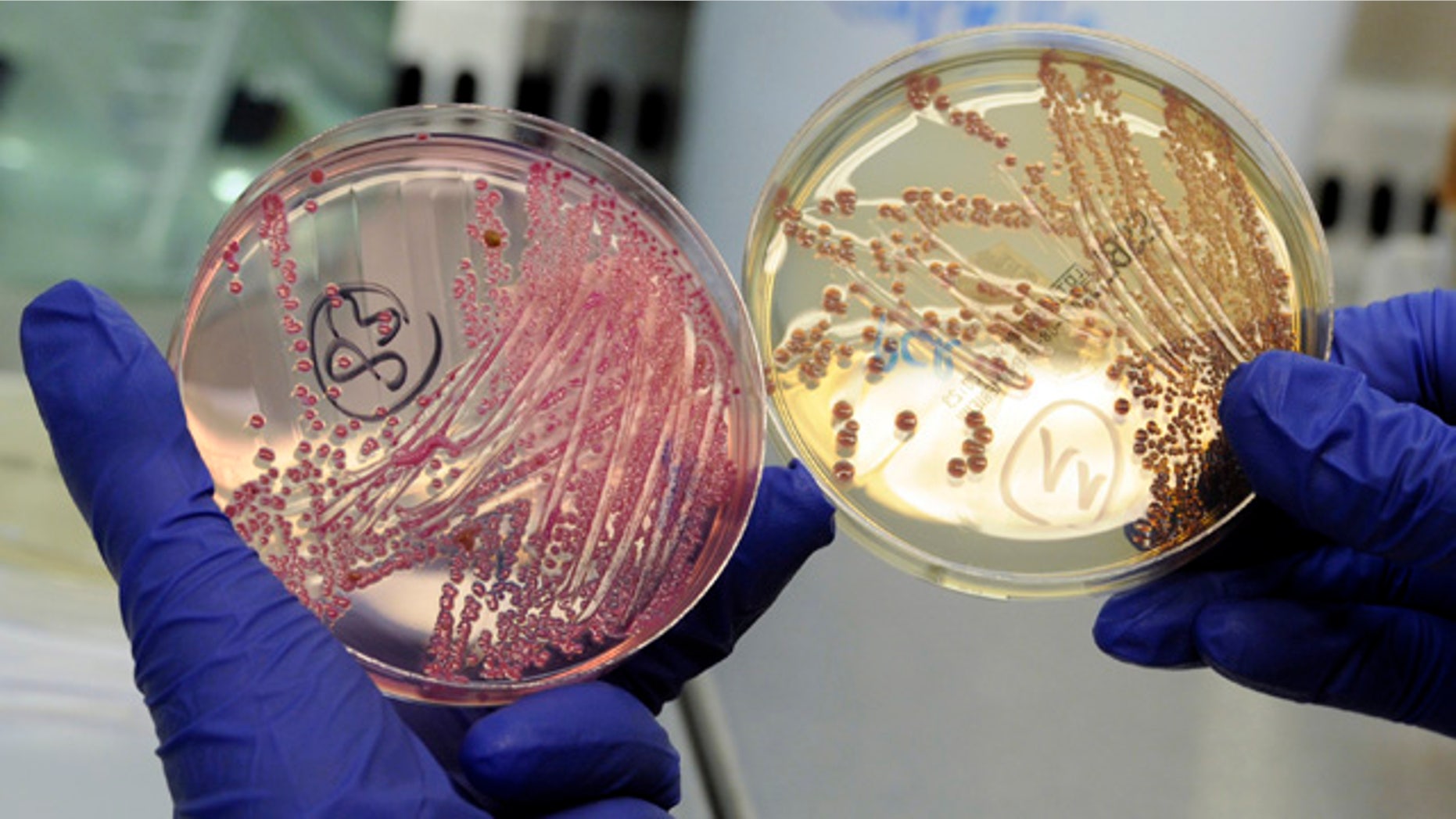

The Strain That Changed Everything

We have to talk about Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, or STEC. If you’ve ever seen a news report about an outbreak linked to ground beef, you’re looking at STEC, specifically the O157:H7 serotype. This isn't just a "run to the bathroom" situation. This bacteria produces a toxin so potent it can literally shut down your kidneys.

In 1993, the Jack in the Box outbreak became a watershed moment for American food safety. It wasn't just a few people getting sick; it was hundreds of people, mostly children, across four states. Four children died. It forced the USDA to declare E. coli O157:H7 an adulterant in ground beef, meaning if it's there, the meat is legally unfit for sale. Before that? It was basically "buyer beware."

But here is the nuance: while we obsess over meat, the landscape has shifted. Nowadays, you’re just as likely—if not more likely—to get an Escherichia coli bacterial infection from a bag of spinach or a bunch of cilantro. Why? Because cattle are the primary reservoir for these bacteria. When their manure runs off into irrigation water used for vegetable crops, the bacteria hitch a ride on the leaves. You can't just "wash it off" easily because the bacteria can actually get inside the stomata (pores) of the leaves.

📖 Related: Why Your Pulse Is Racing: What Causes a High Heart Rate and When to Worry

It’s Not Always Food Poisoning

Everyone forgets about UTIs. If we’re being real, the most common type of Escherichia coli bacterial infection isn't foodborne at all—it's Urinary Tract Infections. Roughly 80% to 90% of community-acquired UTIs are caused by Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC).

These little guys are survivors. They have these hair-like structures called fimbriae that act like tiny grappling hooks. They use them to latch onto the lining of the bladder so they don't get flushed out. Once they’re in, they can form "intracellular bacterial communities," which is a fancy way of saying they hide inside your own cells to dodge your immune system and antibiotics. This is exactly why some people get hit with the same UTI over and over again. It’s not necessarily a "new" infection; it’s the old one coming out of hiding.

The Scary Part: Antibiotic Resistance

We are entering a bit of a "dark ages" for treating some of these infections. Doctors are seeing more cases of ESBL-producing E. coli. ESBL stands for Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase. Basically, the bacteria have learned how to create an enzyme that chews up common antibiotics like penicillin and cephalosporins.

When you go to the doctor with a suspected Escherichia coli bacterial infection, they used to just throw a standard antibiotic at you and call it a day. Now? They often have to wait for culture results to see what the specific strain is actually sensitive to. If it's a resistant strain, they might have to move to "drugs of last resort" like carbapenems. And even those are starting to see resistance in some parts of the world. It’s a literal arms race.

👉 See also: Why the Some Work All Play Podcast is the Only Running Content You Actually Need

Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS)

This is the complication that keeps pediatricians up at night. HUS usually follows the diarrheal stage of an infection with Shiga-toxin-producing strains. The toxin enters the bloodstream and starts destroying red blood cells. These "broken" cells then clog the tiny filtering units in the kidneys.

Symptoms of HUS are subtle at first.

- Extreme paleness.

- Decreased urination (because the kidneys are failing).

- Unexplained bruising.

- Irritability.

If a child has bloody diarrhea and then suddenly stops peeing, it is an absolute medical emergency. There is no "cure" for HUS; doctors just have to provide supportive care—blood transfusions, dialysis—and hope the kidneys recover. Most do, but it can leave lifelong scarring.

Where Does It Actually Hide?

You've probably heard about cross-contamination in the kitchen. Use a separate cutting board for meat, right? Standard stuff. But think about your kitchen sink. Studies have shown that the kitchen sink often has more fecal bacteria than the toilet seat.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Long Head of the Tricep is the Secret to Huge Arms

Think about it. You rinse a chicken or a head of lettuce that might have trace contaminants. The bacteria hang out in the damp drain or on the sponge. Then you wipe down the counter with that same sponge. You've just spread a potential Escherichia coli bacterial infection across every surface where you prep food.

Also, petting zoos. They are notorious. You pet a cute goat, the goat has E. coli in its gut, it rubs against the fence, you touch the fence, and then you eat a popcorn. Boom. It’s that simple. Hand sanitizer helps, but it’s not a magic wand, especially if your hands are visibly dirty. Soap and water are still the gold standard because the mechanical action of scrubbing actually lifts the bacteria off your skin and flushes them down the drain.

Sorting Fact From Fiction

Let’s clear some things up.

- "I cooked the steak, so it's safe." Not necessarily. If it's a whole muscle steak, the bacteria are usually just on the surface. Searing it kills them. But if it's ground beef? The grinding process moves the bacteria from the surface into the very center of the burger. If that burger is pink in the middle, you might be eating live E. coli.

- "It’s just a 24-hour bug." Nope. E. coli symptoms usually don't even start until 3 to 4 days after you eat the contaminated food. If you got sick two hours after lunch, it was likely something else, like Staphylococcus aureus or just plain old indigestion.

- "Antibiotics fix everything." Actually, for certain types of Escherichia coli bacterial infection (like STEC), some doctors advise against antibiotics. Why? Because killing the bacteria all at once can cause them to release a massive "death burst" of toxins into your system, potentially increasing the risk of kidney failure.

Taking Action: The "Expert" Checklist

If you want to actually lower your risk, quit worrying about "chemicals" and start worrying about microbiology.

- Use a thermometer. Stop guessing. Ground beef needs to hit 160°F (71°C). At that temperature, the protein in the bacteria denatures and they die.

- The "Two-Board" System. Have a plastic cutting board for raw proteins and a wooden one for produce. Plastic is easier to sanitize in a high-heat dishwasher after it's touched raw meat.

- Wash your produce, even the "pre-washed" stuff. While the factory wash is good, another rinse at home doesn't hurt, though it's not a guarantee. The best defense is buying from reputable sources and staying tuned to CDC recall notices.

- Hydration is the only real DIY treatment. If you do get a standard, non-toxic E. coli infection, don't rush for anti-diarrheal meds like Imodium. Your body is trying to flush the pathogen out. Let it. Just make sure you're replacing electrolytes. Pedialyte isn't just for kids; it's for anyone losing fluids faster than they can drink them.

- Watch the "Danger Zone." Food left out between 40°F and 140°F is a playground for bacterial replication. Most E. coli populations can double every 20 minutes in the right conditions. That potato salad at the 4th of July picnic? If it's been out for two hours in the sun, it's a biohazard.

Prevention isn't about being a germaphobe; it's about understanding the "fecal-oral route"—which is a gross term for a simple reality. Bacteria move from guts to hands to surfaces to mouths. Breaking that chain at any single point is usually enough to keep you out of the hospital.