It was a Sunday. May 18, 1980. For weeks, the Pacific Northwest had been on edge because the mountain was bulging—literally. Geologists like David Johnston were watching a massive, 450-foot "tumor" growing on the north face of the peak. Everyone knew something was coming, but nobody expected the mountain to unzip sideways. When the eruption of Mount St. Helens finally happened at 8:32 a.m., it didn't just blow its top. It collapsed.

The scale of what happened in those first few minutes is hard to wrap your head around. It wasn't just a volcanic eruption; it was the largest terrestrial landslide in recorded history. A magnitude 5.1 earthquake shook the ground, and the entire north flank of the mountain simply gave up. It slid away at speeds reaching 150 miles per hour. If you were standing there, you wouldn't have seen a fountain of lava. You would have seen the world turning inside out.

The Side-Blast That Nobody Saw Coming

Most people think of volcanoes as giant chimneys. You expect the smoke and fire to go straight up. But Mount St. Helens was different because of that "cryptodome" of magma pushing against the side. When the landslide removed the weight of the mountain's north face, it was like popping the cork on a pressurized bottle of champagne that had been shaken for two months.

The lateral blast was terrifyingly fast. We’re talking 300 to 670 miles per hour. It overtook the landslide in seconds. It didn't just knock trees down; it stripped the bark off them and then snapped 200-foot-tall Douglas firs like they were toothpicks. Over 230 square miles of forest vanished. Just gone.

Geologist David Johnston was stationed at an observation post six miles away—a spot thought to be relatively safe. His last words over the radio were, "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!" He was gone seconds later. The blast was so hot and powerful that it reached temperatures of 660°F. Honestly, the sheer speed of the destruction is why 57 people lost their lives that day, even though many were miles outside the "danger zone."

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

Gray Snow and Total Darkness

While the blast was doing its work on the ground, a vertical plume of ash was screaming into the atmosphere. It hit 80,000 feet in less than 15 minutes. That’s nearly 15 miles high. For folks in eastern Washington, the sky didn't just get cloudy. It turned pitch black in the middle of the day.

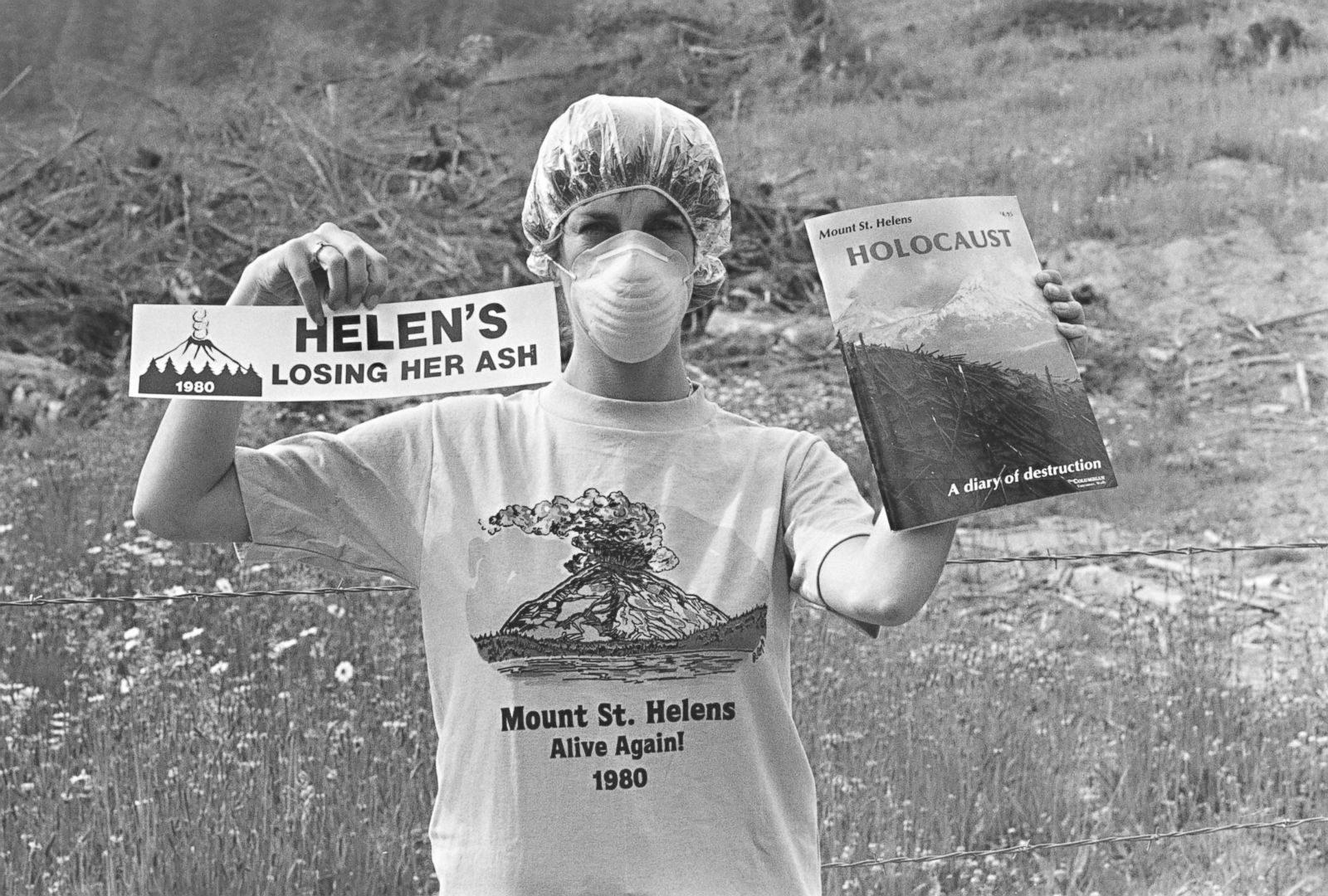

In places like Yakima and Spokane, streetlights clicked on at noon. People thought the world was ending. Ash isn't like soft wood smoke; it’s pulverized rock and glass. It's heavy. It’s abrasive. It smells like sulfur—that rotten egg smell that sticks in the back of your throat.

- 540 million tons of ash eventually blanketed 11 states.

- It clogged car engines and grounded planes.

- In some spots, it was several inches deep, looking like a weird, gray, apocalyptic snow.

The economic hit was massive too. We're talking $1.1 billion in 1980 dollars, which is roughly $3.5 billion today. Bridges were swept away by lahars—massive mudflows that had the consistency of wet concrete—which tumbled down the Toutle and Cowlitz rivers. These mudflows were powerful enough to carry entire houses and logging trucks downstream like they were toys.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Aftermath

There’s this common idea that the area around Mount St. Helens became a permanent moonscape. People thought life would take centuries to return. They were wrong.

👉 See also: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

Nature is surprisingly scrappy. Within just a few years, plants started poking through the ash. Small mammals like pocket gophers actually helped the recovery by churning the soil, bringing seeds and nutrients to the surface. Today, if you visit the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, you’ll see a vibrant, albeit different, ecosystem. The "Pumice Plain" is still a bit stark, but it’s crawling with life.

One of the weirdest things? Spirit Lake. The landslide slammed into the lake, pushing a massive wave of water 850 feet up the surrounding hills. This wave dragged thousands of trees back into the lake. Decades later, a giant "log mat" still floats on the surface. It’s a literal floating graveyard of the 1980 forest.

Why Mount St. Helens Still Matters

The 1980 eruption changed how we monitor volcanoes globally. Before this, "lateral blasts" weren't really at the top of the worry list. Now, every "bulge" on a volcano is treated with extreme suspicion. We have GPS sensors that can detect movements as small as a few millimeters.

But is it over? Not really. The mountain is still active. It had a long, slow eruption from 2004 to 2008 where it built a new lava dome inside the crater. It's breathing. It’s recharging.

✨ Don't miss: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

If you're planning to head out there, don't just go to the visitor center and leave.

- Visit Johnston Ridge Observatory: It’s named after David Johnston and sits right in the path of the blast. The view of the crater is haunting.

- Check the Seismographs: You can see real-time data of the mountain "shaking." It’s a good reminder that the ground isn't as solid as we think.

- Hike the Hummocks Trail: This takes you through the actual debris of the landslide. You’re literally walking on the pieces of the mountain that fell off.

- Respect the Zone: Stick to the trails. The recovery area is still a massive scientific laboratory, and the soil crust is delicate.

The eruption of Mount St. Helens wasn't just a historical event; it was a reset button for the entire region. It showed us that even the most permanent-looking landmarks can change in 20 seconds. We're still learning from the ash it left behind.

To stay informed on current volcanic activity, you can monitor the USGS Volcano Hazards Program updates. If you're planning a hike, always check the Mount St. Helens Institute for trail conditions and permits, especially for the summit climb which requires a specialized pass due to high demand.