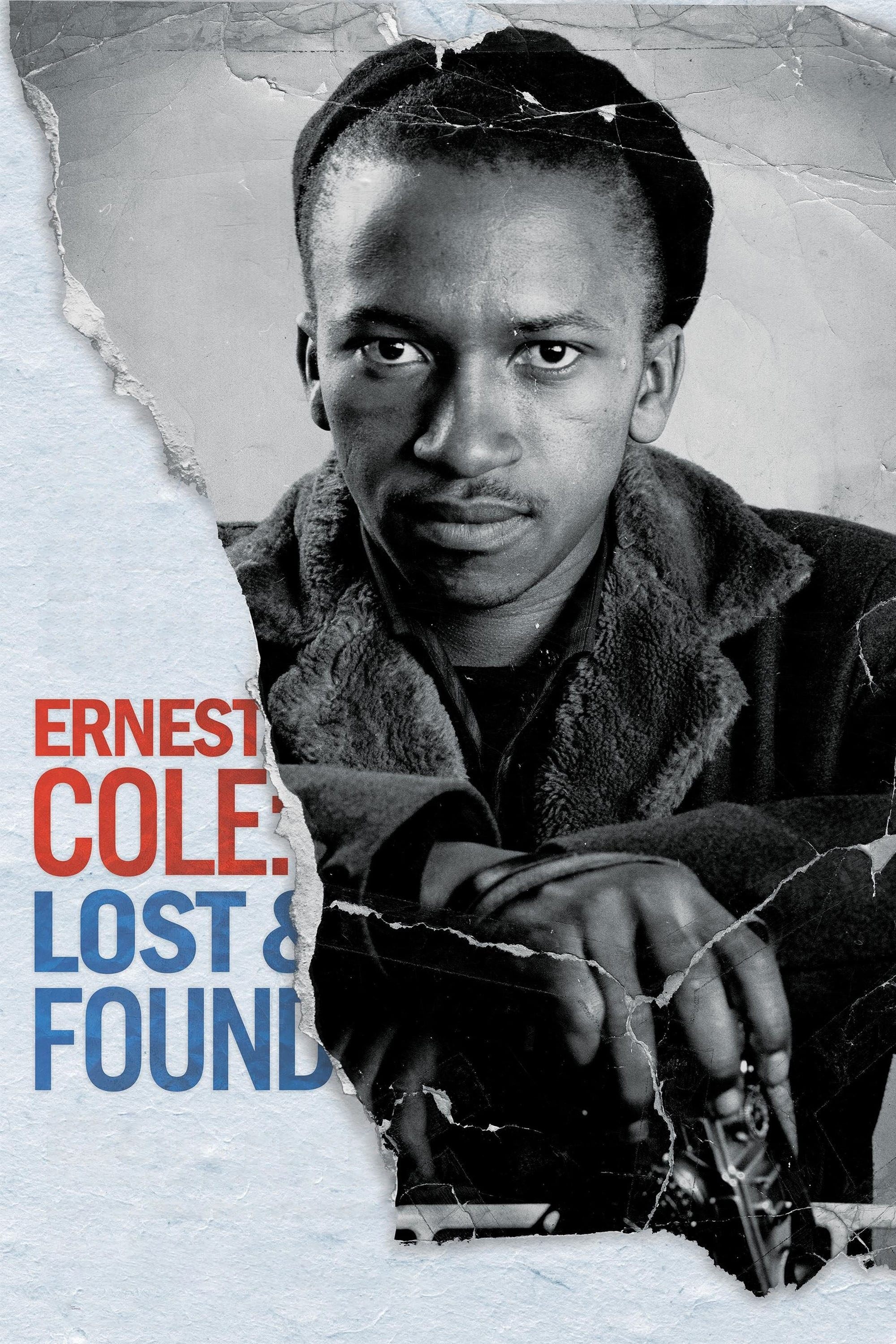

He died penniless in a New York City hospital. It was 1990, and the world was changing. Just days before Ernest Cole took his last breath, Nelson Mandela walked out of Victor Verster Prison a free man. Cole, the man who had done more than almost any other artist to show the world the jagged, bloody reality of apartheid, didn't live to see the liberation he'd spent his youth documenting. He was only 49.

For decades, that was the end of the story. A tragic "what if."

🔗 Read more: Fox 32 Chicago Schedule Explained: What You’re Actually Missing

Then, in 2017, something weird happened. A bank in Stockholm, Sweden, opened up a few safety deposit boxes that hadn't been touched in forty years. Inside? More than 60,000 negatives. This is where Ernest Cole: Lost and Found begins. It’s not just a documentary; it’s a resurrection of a man who literally risked his life to smuggle the truth out of South Africa in the 1960s.

Why Ernest Cole: Lost and Found is making people rethink history

Honestly, most people hadn't heard of Ernest Cole until Raoul Peck—the guy who directed I Am Not Your Negro—decided to dig into this archive. Peck doesn't do typical "talking head" documentaries. You won't see a bunch of professors in cardigans explaining why Cole was important. Instead, he uses Cole’s own words, narrated with this haunting, gravelly tone by LaKeith Stanfield.

It feels like Cole is talking to you from the grave. Kinda spooky, but mostly just deeply moving.

The "Lost" part of the title is literal. When Cole fled South Africa in 1966, he had to leave almost everything behind. He was "reclassified" as Coloured just so he could work as a photographer, a move that allowed him into areas where Black South Africans were banned. He took photos of miners being stripped for examinations, of children sleeping on cardboard, and of the "Europeans Only" signs that defined his existence.

The discovery that changed everything

When those 60,000 negatives were found in Sweden, it blew the doors off what we knew about his career. We always thought he just stopped working after his famous book, House of Bondage, came out in 1967.

Nope.

He was busy. He was in the U.S. shooting the Jim Crow South and the streets of Manhattan. The film shows how he looked at America and basically went, "Wait, this is just South Africa with a different accent." He saw the same segregation, the same systemic grind.

But here’s the kicker: the American editors didn't want to see it. They wanted him to be the "Anti-Apartheid Guy," not the "Critique of American Racism Guy." They wanted him to stay in his lane. He refused.

The man behind the lens

Cole wasn't some saint. He was complicated. He was stubborn.

💡 You might also like: Eyes Wide Shut: Why Kubrick’s Final Movie Still Haunts Us

The documentary doesn't shy away from the fact that he struggled. Hard. He went through periods of homelessness in New York. He felt like a ghost. Imagine being the guy who published one of the most important photo books of the 20th century and then not being able to afford a sandwich.

That’s the "Lost" part of his life. He lost his connection to his home. He lost his health to pancreatic cancer. He even lost control of his own work for decades.

What the Swedish archive revealed

- The American South: Thousands of photos showing the parallels between the U.S. and South Africa.

- New York City: A raw, unvarnished look at 1970s Manhattan through the eyes of an outsider.

- Personal Notes: Diaries and letters that show a man who was deeply depressed but never stopped seeing.

Raoul Peck manages to weave these images together so they don't just feel like an old slideshow. They feel urgent. You look at a photo from 1964 and you think about 2026. It’s that relevant.

Is it worth the watch?

If you're into photography, it's a must. If you care about history, it’s essential.

But even if you just like a good mystery, the story of how 60,000 negatives ended up in a Swedish vault is fascinating. There’s still no clear answer on why they were there or who exactly put them in those boxes. It’s one of those historical quirks that feels like it belongs in a movie.

📖 Related: Dylan Reynolds Video Editor: What Most People Get Wrong

The film won the L'Oeil d'or (the documentary prize) at Cannes for a reason. It’s beautiful, sure, but it’s also angry. It’s an indictment of how we treat Black artists and how easily we "lose" their contributions when they don't fit a convenient narrative.

Actionable insights for those interested in Cole’s legacy

If you're moved by the story in Ernest Cole: Lost and Found, don't just stop at the credits. Here is how you can actually engage with this history:

- Check out "The True America": This is the newer book (and exhibition) that features the work found in that Swedish vault. It’s the stuff Cole was told wouldn't sell.

- Find "House of Bondage": It was recently republished by Aperture. It was banned in South Africa for 22 years, which is usually a sign that it’s worth reading.

- Support the Ernest Cole Family Trust: The negatives are back with his family now. They are the ones doing the hard work of cataloging thousands of images that haven't been seen in half a century.

- Look for the documentary on streaming: Magnolia Pictures has been handling the distribution, so it's hitting major VOD platforms like Apple TV and Prime Video.

Ernest Cole didn't get his flowers while he was alive. The least we can do is look at what he left behind. It’s all right there in the title: he was lost, but through this film and that bank vault, he’s finally being found.

To truly understand the impact, start by looking up his most famous photograph: the one of the Black man being searched by a white policeman. Then, watch the film to see the 59,999 other stories he was trying to tell.