Chemistry is weird. You’ve probably sat in a lab, staring at a beaker that’s getting ice-cold for no apparent reason, or maybe you’ve felt the sudden, alarming heat of a hand warmer on a winter morning. These aren't magic tricks. They’re just energy moving house. When we talk about an energy diagram endothermic vs exothermic process, we’re basically looking at a bank statement for molecules. Some reactions spend energy to get started and never quite make it back into the black, while others are like a jackpot that dumps heat into the surroundings.

It’s all about the "enthalpy," a fancy word for the total heat content of a system. But honestly? Forget the jargon for a second. Think of it as a hill.

The Hill You Have to Climb

Every single chemical reaction, whether it’s burning rocket fuel or just rusting a nail, starts with a struggle. This is the activation energy ($E_a$). Even if a reaction wants to happen, it needs a kickstart. You don't just see a piece of wood burst into flames; you need a match. That match provides the initial energy to break existing chemical bonds so new ones can form.

On an energy diagram, this is the peak. The view from the top is what chemists call the "activated complex." It’s a messy, unstable middle ground where the old bonds are halfway broken and the new ones are just starting to say hello.

Exothermic Reactions: The Great Energy Dump

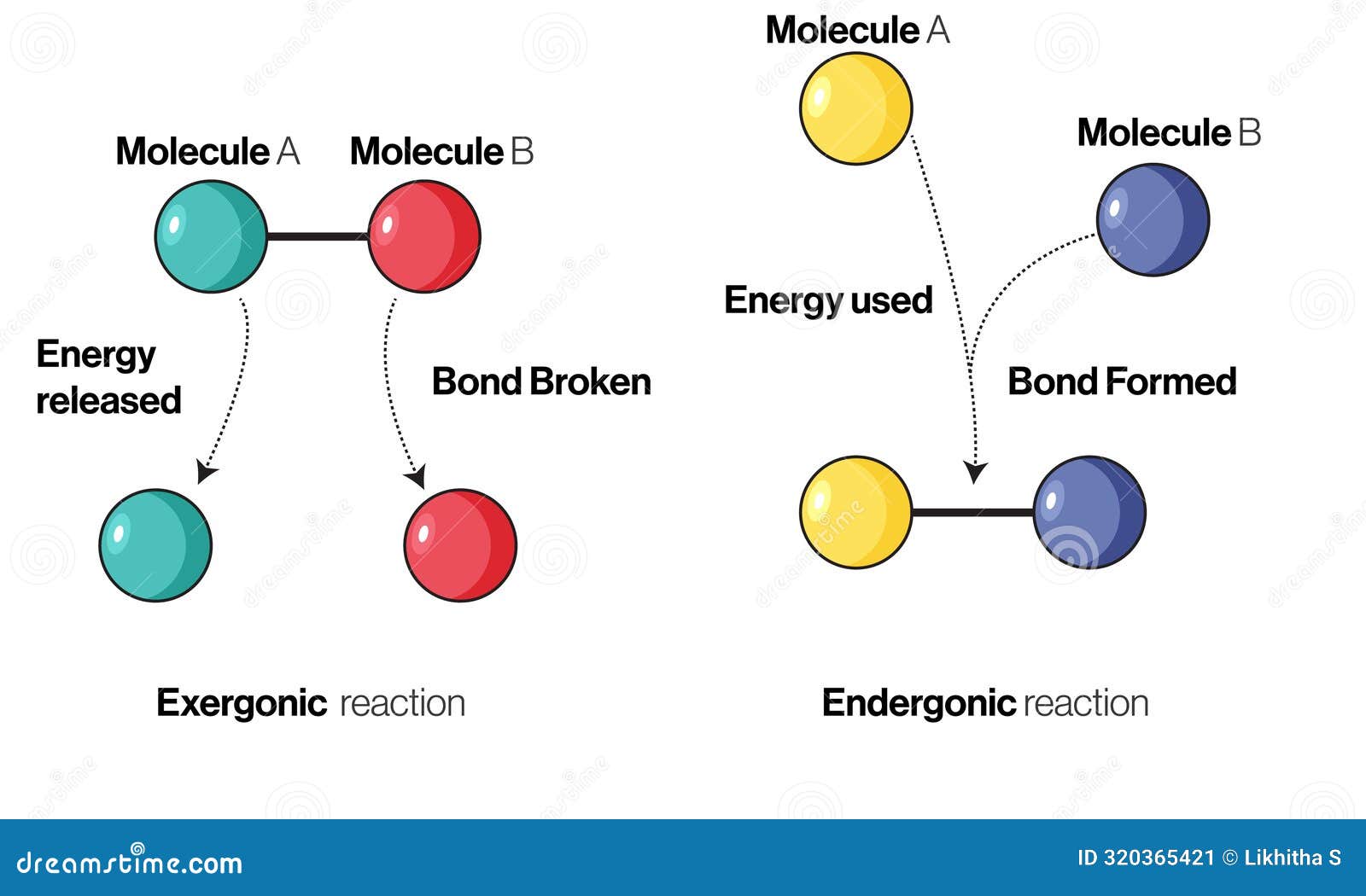

Most of the reactions we rely on to survive are exothermic. Your body breaking down glucose? Exothermic. Your car engine firing? Exothermic. In an energy diagram endothermic vs exothermic comparison, the exothermic side is the one that finishes lower than it started.

The math is simple, even if the molecular physics isn't. You start with reactants at a certain energy level. You climb the activation energy hill. Then, you slide down the other side—and you keep sliding until you’re way below your starting point. Because the products have less energy than the reactants, that "missing" energy has to go somewhere. It usually leaves as heat or light.

🔗 Read more: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

That’s why a campfire feels warm. The chemical bonds in the wood and oxygen are being traded for much stronger, more stable bonds in carbon dioxide and water. Because the new bonds are more "comfortable" (lower energy), they release the excess. In these diagrams, the change in enthalpy ($\Delta H$) is negative. It’s a loss for the molecules, but a gain for your frozen fingers.

Endothermic Reactions: The Energy Vampires

Now, flip the script. Ever used an instant cold pack? You crack the inner pouch, the chemicals mix, and suddenly it’s freezing. This is an endothermic reaction. It’s literally sucking the heat out of your bruised ankle to fuel its own chemical transformation.

On an energy diagram endothermic vs exothermic, the endothermic plot looks like a grueling uphill climb that never really levels out. The products end up with more potential energy than the reactants started with.

How does this happen? The energy has to come from the environment. It takes more work to break the bonds of the reactants than is "paid back" when the products form. You’re essentially storing energy in the chemical bonds. Photosynthesis is the ultimate example here. Plants take low-energy water and carbon dioxide, steal some photons from the sun, and build high-energy sugar molecules. Without that constant solar input, the reaction stops dead. Here, $\Delta H$ is positive. The system is gaining.

Why the "Flat Line" in Your Textbook is a Lie

If you look at a standard classroom energy diagram, the lines are usually smooth and perfect. In reality, chemical reactions are rarely a single-step leap. Most things you see in a lab involve a "mechanism"—a series of tiny, frantic mini-reactions.

💡 You might also like: Brain Machine Interface: What Most People Get Wrong About Merging With Computers

Each step has its own little hill. Sometimes you’ll see an energy diagram with two or three humps. The tallest hump is the bottleneck, the "rate-determining step." If a reaction is moving too slow, it’s usually because that specific hill is too high for the molecules to get over at their current temperature.

Catalysts: The Secret Tunnel

We can't talk about an energy diagram endothermic vs exothermic without mentioning catalysts. Whether it’s the enzymes in your saliva or the platinum in your car’s catalytic converter, these things are cheat codes.

A catalyst doesn't change where you start (reactants) or where you end (products). It doesn't change the $\Delta H$. What it does is provide an alternative path with a much lower activation energy. It’s like finding a tunnel through the mountain instead of climbing over the peak. This allows the reaction to happen much faster, or at much lower temperatures, than it normally would.

Real World Stakes: Why This Matters for 2026

We’re currently obsessed with hydrogen fuel and carbon capture. Both of these technologies live and die by these diagrams. Splitting water to get hydrogen is a massive endothermic mountain. We’re currently looking for better catalysts to make that hill smaller so we can produce green fuel without wasting half the energy we put in.

On the flip side, capturing $CO_2$ from the air is also an energy-heavy lift. The "ideal" reaction would be one that captures the gas and then releases it for storage using as little energy as possible—meaning we want a reaction profile that is barely endothermic, just enough to be stable but not so much that it's a power hog.

📖 Related: Spectrum Jacksonville North Carolina: What You’re Actually Getting

How to Read the Graph Like a Pro

If you’re looking at a graph and trying to figure out what’s going on, just look at the tails.

- Left tail higher than right tail? It’s exothermic. Heat is leaving. The beaker gets hot.

- Right tail higher than left tail? It’s endothermic. Heat is entering. The beaker gets cold.

- The gap between the start and the peak? That’s the activation energy. High peak means a slow, stubborn reaction.

- The gap between the start and the end? That’s your Enthalpy ($\Delta H$). That’s the "profit" or "loss" of the reaction.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Lab or Project

If you’re trying to control a reaction based on its energy profile, keep these three things in mind.

First, temperature is your throttle. For endothermic reactions, adding heat isn't just a suggestion; it's the fuel. If you don't keep the heat coming, the reaction will literally starve and stop. For exothermic reactions, be careful. Because they release heat, they can sometimes "run away." The heat they release provides the activation energy for the neighboring molecules, which release more heat, leading to an explosion if not cooled down.

Second, don't confuse "spontaneous" with "fast." A reaction can be highly exothermic (it wants to release a ton of energy) but have such a massive activation energy hill that it never starts on its own. Diamonds turning into graphite is actually an exothermic process, but the hill is so high that your wedding ring isn't going to turn into a pencil lead anytime in the next billion years.

Third, always check your state symbols. Whether a substance is a liquid, gas, or solid changes its starting energy level. Boiling water is endothermic; condensing steam is exothermic. If you’re calculating $\Delta H$ for a report, make sure you aren't accidentally using the values for liquid water when you’re actually producing steam. That small mistake will wreck your data.

Chemistry isn't just about mixing liquids until they change color. It’s a constant tug-of-war between stability and chaos, and the energy diagram is the map that shows you who’s winning.