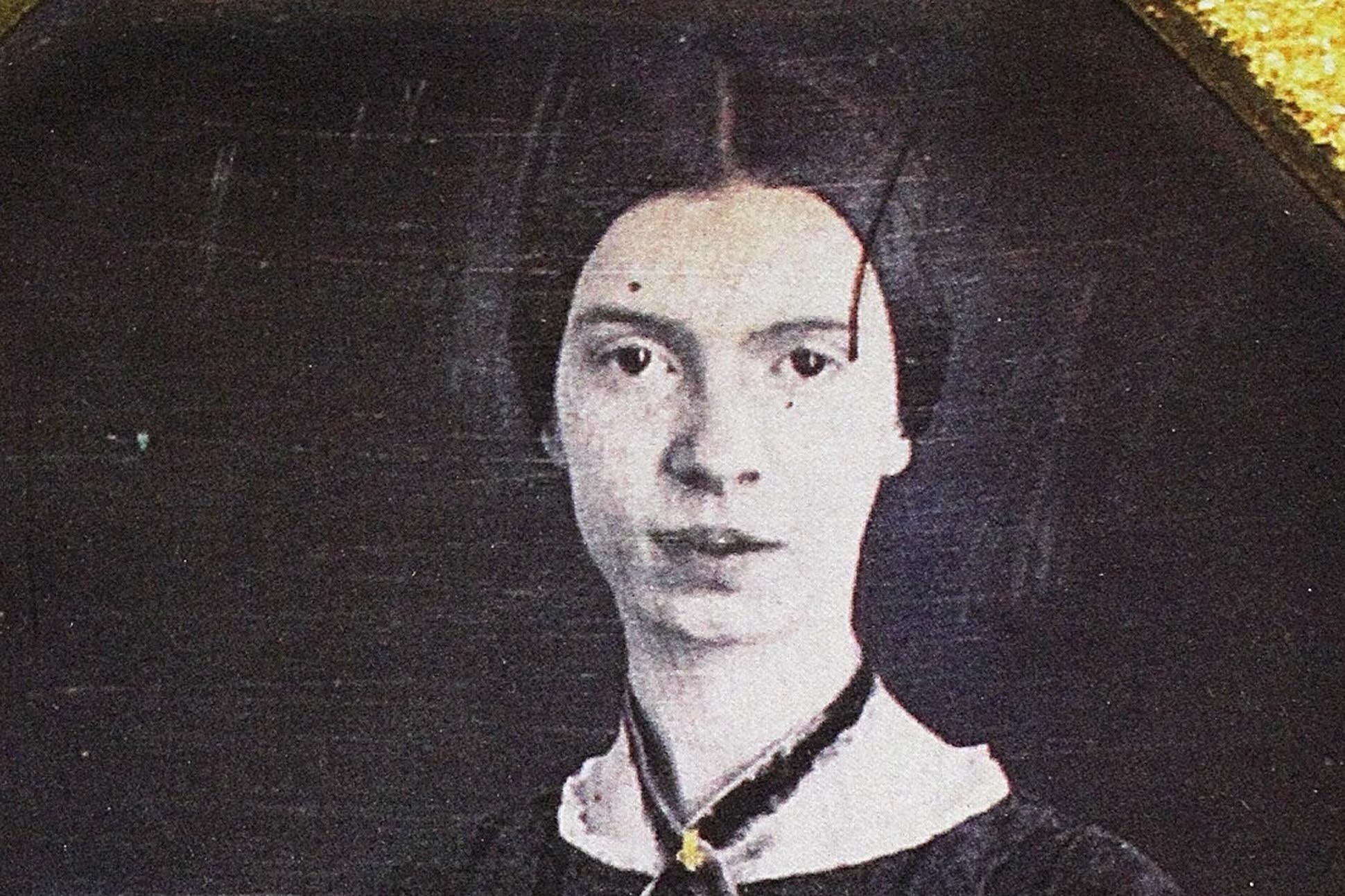

She stayed in her room. Mostly. Emily Dickinson spent a massive chunk of her adult life tucked away in a yellow brick house in Amherst, Massachusetts, wearing white and avoiding the neighbors. You’d think that would make her the last person to ask for advice on how to live, right? Wrong. It turns out that emily dickinson poems about life are some of the most electric, terrifying, and weirdly comforting things ever written in the English language.

She wasn't some fragile flower. She was a scientist of the soul.

Dickinson didn't write for the "Likes" or the "Shares." In fact, she barely published anything while she was breathing. She was basically the original "if you know, you know" underground artist. When her sister Lavinia found that cherry-wood chest full of nearly 1,800 hand-sewn booklets—or fascicles—after Emily died in 1886, the world finally got a glimpse of a mind that had been mapping out the human experience with surgical precision.

The Myth of the Recluse vs. The Reality of the Poetry

People love the "Crazy Recluse" narrative. It's easy. It’s a trope. But if you actually sit down with her work, you realize she wasn't hiding from life; she was focusing on it so intensely it probably hurt. Her poems about life aren't about grand adventures or climbing mountains. They are about the tiny, tectonic shifts that happen inside your chest when you wake up on a Tuesday and realize you're alive.

Take Poem 324, often titled "Some keep the Sabbath going to Church." While everyone else was putting on their Sunday best to go hear a sermon, Emily was hanging out in her garden. She wrote: “With a Bobolink for a Chorister – / And an Orchard, for a Dome –”

She was basically saying, "I don't need the building to find the meaning." That’s a gutsy move in the 1800s. She found the divine in the dirt and the birds. Honestly, it’s the most relatable thing ever. Who hasn’t felt more "connected" on a solo hike than in a crowded room?

Why Her Style Still Feels Like a Modern Text Message

Have you noticed the dashes? The random Capitalization?

Dickinson's grammar is a mess by traditional standards, but it’s a masterpiece of pacing. Those dashes—those little horizontal breaths—are where the real poem happens. They represent the pauses in our own thinking. Life doesn't happen in perfect, flowing sentences. It happens in bursts. It happens in "Wait—did I just—oh, okay."

She used common meter, which is the same beat as "The Yellow Rose of Texas" or the "Gilligan’s Island" theme. It’s catchy. It’s folk-like. But then she fills that simple structure with words like "intercalary" or "circumference." It’s this wild juxtaposition of the simple and the cosmic.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

Dealing with the "Dark Side" of Being Alive

You can’t talk about emily dickinson poems about life without talking about the heavy stuff. She was obsessed with the boundary between living and not-living.

“I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” she starts one poem.

That is one of the most accurate descriptions of a mental breakdown ever recorded. She describes the "Mourners to and fro" treading until "Sense was breaking through." She doesn’t sugarcoat it. She doesn't give you a "hang in there" kitten poster. She acknowledges that sometimes, being alive feels like a plank in your floor just gave way and you’re dropping through worlds.

There's a specific kind of bravery in that.

The "Certain Slant of Light" Problem

In Poem 258, she talks about that "certain Slant of light, / Winter Afternoons – / That oppresses, like the Heft / Of Cathedral Tunes –"

We’ve all felt that. That weird, unnamable Sunday-scary feeling when the sun hits the wall at a certain angle in February and you suddenly feel the weight of existence. She gave us a vocabulary for the moods we didn't think anyone else had. Scholars like Helen Vendler have spent decades parsing how Dickinson managed to pin down these ephemeral feelings. It's not just "sadness." It's "imperial affliction." It's a "Heavenly Hurt."

Hope is the Thing with Feathers (And Talons)

Okay, let's talk about the big one. Poem 254.

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers – / That perches in the soul –”

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

People use this on greeting cards all the time, but they usually miss the grit. Dickinson’s version of hope isn't a fluffy little bird that sings when things are great. It’s a bird that "sings the tune without the words — / And never stops — at all —."

The key word there is never.

She’s saying hope is a relentless, almost annoying instinct. It stays warm in the "chillest land" and on the "strangest Sea." It doesn’t ask for a "crumb" from you. It’s just... there. Persistent. It’s an evolutionary survival mechanism wrapped in a metaphor. That is the genius of how she viewed the human condition. Life is hard, but we are weirdly hardwired to keep going.

The Science and Botany of the Soul

Emily wasn't just a "poetess." She was a gardener. She studied botany at Amherst Academy. She had an herbarium where she pressed over 400 different species of plants.

This matters because when she writes about life, she uses the language of growth and decay. She understood that life requires dirt. She understood that for a flower to bloom, it has to break out of its own skin.

“The Grass so little has to do – / A Sphere of simple Green –”

She envied the grass. She looked at the natural world and saw a version of life that was effortless, compared to the "profound" labor of being a human with a brain that won't shut up.

Misconceptions About Her "Small" Life

Critics for years tried to dismiss her because she didn't travel. They thought her poems about life were limited because she stayed in Amherst. But as she famously wrote, "To fill a Gap / Insert the Thing that caused it— / Do not patch it with a Microbe / Or a Wight of Air—"

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

She didn't need to go to Paris. She had the entire universe inside her skull. She proves that the scale of your life isn't measured by your stamps in a passport, but by the depth of your attention. If you pay enough attention to a single bee or a single breeze, you can find the infinite.

How to Read Dickinson Without Feeling Like You’re in High School English

If you want to actually enjoy these poems, stop trying to "solve" them. They aren't riddles with a single answer. They are experiences.

- Read them out loud. Listen to the slant rhymes. Notice how "Gate" and "Mat" don't quite rhyme, but they feel right. That’s intentional. It creates tension.

- Ignore the titles. She didn't give them titles. Editors did that later. Just look at the numbers or the first lines.

- Look at the variants. Dickinson often wrote multiple options for a single word in her manuscripts. She’d put a little "+" sign and offer a synonym in the margin. She knew that life is about choices, and sometimes two different words are both "true."

- Accept the ambiguity. If you finish a poem and think, "I have no idea what just happened," you're doing it right. She was writing about the "Undiscovered Continent" of the human mind. It's supposed to be a bit blurry.

The Actionable Insight: Living Like Emily (Sorta)

You don't have to lock yourself in a bedroom to get what Emily was talking about. Her poems about life are ultimately a call to radical presence.

In a world of TikTok and 24-hour news cycles, her work is a reminder to look at the "Slant of light" in your own living room. It's a reminder that "Forever – is composed of Nows –" (Poem 624).

If you want to live a "Dickinsonian" life:

- Notice the small stuff. Find one thing in nature today—a leaf, a bug, the way the clouds are moving—and look at it for three full minutes.

- Don't fear the solitude. She showed us that being alone isn't the same as being lonely. It's where the best thinking happens.

- Embrace the "Dash." Allow yourself those pauses in your day. Not every moment needs to be filled with productivity or noise.

- Write it down. You don't have to be a genius. Just try to describe a feeling using a metaphor that feels "wrong" but looks right.

Emily Dickinson’s poems about life are still relevant because the human heart hasn't changed much since 1860. We still feel the "Heft" of sad afternoons. We still have that "feathered thing" perching in our souls when things get dark.

She just had the guts to put it on paper.

Where to go from here

To truly dive in, pick up the The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition edited by R.W. Franklin. It’s the most "raw" version of her work. Start with Poem 657 (I dwell in Possibility). It’s her manifesto. It’s the ultimate argument for why poetry, and life, should be wide open, with "numerous doors" and "windows superior" to the mundane world.

Stop reading about her and go read her. That’s what she would’ve wanted. Well, actually, she might have just wanted to be left alone with her plants, but you get the point.