Honestly, if you were a woman in 18th-century Paris with a paintbrush and a dream, the odds were basically stacked against you. Hard. You couldn't attend the official art schools. You couldn't draw from live nude models (scandalous!). You were basically expected to paint some flowers, get married, and disappear into the background of history.

But Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun didn't do that. Not even close.

She became the highest-paid portraitist in Paris, the "bestie" of the most hated queen in French history, and a savvy survivor who turned a terrifying exile into a European victory tour. While the French Revolution was busy chopping off heads, she was busy reinventing what it meant to be a professional female artist.

The Hustle of a Teenage Prodigy

Elizabeth wasn't born into the high life. Her dad, Louis Vigée, was a minor pastel painter who realized his daughter was a genius when she was still in pigtails. He died when she was only 12, leaving her with a stepfather she reportedly couldn't stand.

She had to work. Fast.

By 15, she was already painting portraits professionally to support her mom and brother. She didn't have a license, and the authorities actually seized her studio equipment at one point because she wasn't part of a guild. Did she quit? Nope. She just joined the Académie de Saint-Luc and kept right on going.

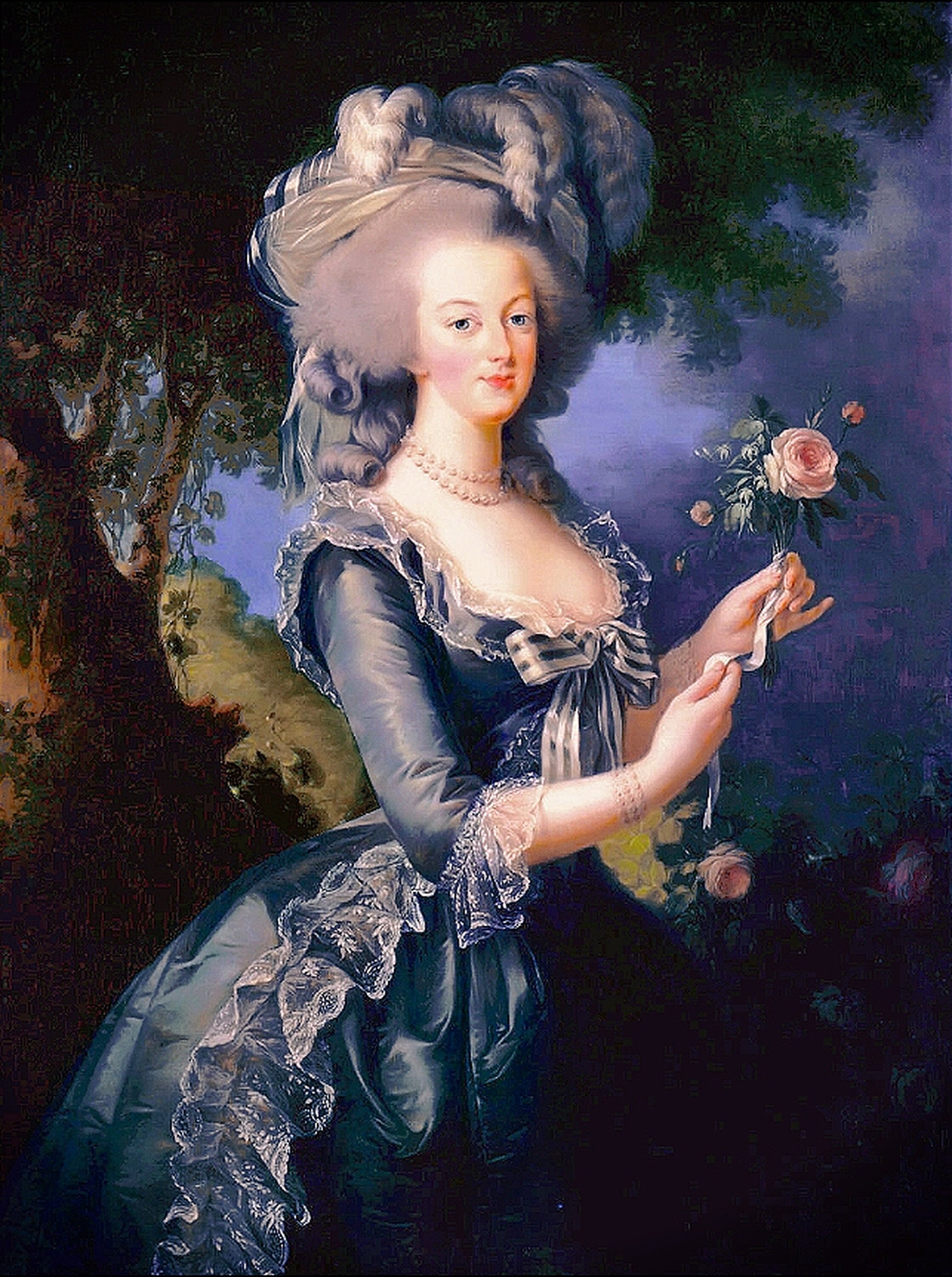

She had this uncanny ability to make people look... well, better. But it wasn't just "filter" level flattery. She captured a sort of luminous, dewy skin tone and a relaxed vibe that made the stiff, powdered-wig crowd look human for once.

Why Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun and Marie Antoinette Clicked

In 1778, Elizabeth got the call that changed everything: an invite to Versailles to paint Marie Antoinette.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

The Queen was 23. Elizabeth was 23. They hit it off.

Over the next decade, Elizabeth painted the Queen about 30 times. They didn't just do formal sittings; they sang duets together. Elizabeth even famously picked up her own brushes after dropping them in front of the Queen—a massive breach of etiquette that Marie Antoinette brushed off with a smile.

But this friendship was a double-edged sword.

The "Chemise" Scandal

In 1783, Elizabeth painted Marie Antoinette en Gaulle. The Queen was wearing a simple, white muslin dress that looked... kinda like a nightgown. The public went nuclear. They thought it was disrespectful to the monarchy and, weirder still, unpatriotic because they thought the fabric looked English.

Elizabeth had to pull the painting from the Salon and quickly paint a new one with the Queen in formal blue silk. It was a lesson in PR that neither of them would ever forget.

Breaking the "Glass Ceiling" at the Royal Academy

Getting into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture was the ultimate goal, but women were strictly limited. Plus, Elizabeth was married to Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun, who was an art dealer. Academy rules forbade members from being married to anyone involved in the "trade" of art.

Basically, they tried to blackball her.

🔗 Read more: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

Marie Antoinette had to personally lean on her husband, King Louis XVI, to issue a royal decree to force the Academy to let Elizabeth in. She became one of only four women allowed. It wasn't exactly a warm welcome, but she was in. She used her "reception piece," Peace Bringing Back Abundance, to prove she could handle serious allegorical subjects, not just pretty faces.

Running for Her Life: The Exile Years

When the Bastille fell in 1789, Elizabeth knew she was in trouble. Her face was literally synonymous with the Queen's. She was the "Royalist painter." People were already spreading nasty rumors about her finances and her personal life.

On the night the royal family was dragged from Versailles to Paris, Elizabeth grabbed her daughter, Julie, and some cash and fled the country in a public coach.

She was gone for 12 years.

Most people would have crumbled, but Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun was a powerhouse. She turned her exile into a massive career expansion. She moved through Italy, Austria, and eventually Russia, where she stayed for six years.

- In Rome: She was elected to the Academy of St. Luke.

- In Naples: She painted the Queen of Naples (who was Marie Antoinette’s sister).

- In Russia: She became a favorite of Catherine the Great’s court.

She charged astronomical prices. She worked constantly. While her husband back in Paris had to divorce her to keep his property from being seized by the state, Elizabeth was out there becoming an international celebrity.

The Smile That Shocked Paris

If you look at Elizabeth's 1787 Self-Portrait with Her Daughter, you’ll notice something weird: she’s smiling. And you can see her teeth.

💡 You might also like: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

Today, that’s just a "selfie" vibe. In the 1780s? It was a scandal. Traditional art didn't do teeth. It was considered "low class" or even suggestive. Elizabeth didn't care. She wanted to capture maternal love and real human emotion. She was moving away from the stiff Rococo style toward something more natural and Neoclassical, even if the critics weren't ready for it.

The Bittersweet Return

Elizabeth finally made it back to France in 1802, but the world she knew was gone. Her friend the Queen was dead. Her marriage was a mess (though she eventually reconciled with her ex-husband in a "friendly roommates" kind of way).

Worst of all, she had a massive falling out with her daughter, Julie. Julie wanted to marry a Russian official Elizabeth didn't approve of, and the two were estranged for years. It’s a tragic footnote for a woman who spent so much of her career painting "ideal" motherhood.

She lived to be 86, writing her memoirs (Souvenirs) and painting until the end. She died in 1842, having survived the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the restoration of the monarchy.

How to Apply the "Le Brun" Method Today

Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun wasn't just a painter; she was a master of personal branding and resilience. Here is how you can take a page from her book:

- Diversify your network. When France became unsafe, Elizabeth had connections in every major European capital. Never rely on just one "client" or one market.

- Control the narrative. Elizabeth wrote her own memoirs to make sure history remembered her version of events. In a world of social media, you have to be the primary source of your own story.

- Flattery with substance. Her portraits worked because they weren't just "pretty"—they felt alive. Whether you're writing a resume or a pitch, find the "luminous" version of the truth.

- Embrace the "Chemise" moments. When you face a PR disaster or a failure, pivot immediately. Elizabeth replaced her scandalous painting within days. Speed is a competitive advantage.

To truly understand her impact, start by looking at her Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat at the National Gallery in London. It’s an homage to Rubens, but it’s 100% Elizabeth—confident, professional, and looking you right in the eye. That’s the gaze of a woman who knew exactly what she was worth.