Imagine being married to one of the most famous kings in history—a man known for his military genius, his flute playing, and his sharp wit—and having him basically ignore your existence for forty years. That was the reality for Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern. Honestly, her life sounds like a Gothic novel, but without the romantic ending. Most people who study Frederick the Great barely mention her. She’s often just a footnote, the "unloved wife" who stayed in a separate palace while he built Sanssouci. But if you look closer, Elisabeth Christine wasn't just a victim. She was a survivor who managed to run the entire Prussian court on her own while her husband was off fighting wars or hanging out with Voltaire.

She was born in 1715 into the house of Brunswick-Bevern. Her childhood wasn't exactly a fairytale, but it was stable enough until the Prussian "Soldier King," Frederick William I, decided she was the perfect match for his rebellious son. The Crown Prince, who would become Frederick the Great, hated the idea. He didn't hate her personally at first; he hated that his father was forcing the marriage to please the Austrians. He even threatened suicide. He told his sister, Wilhelmine, that there could never be love between them.

Talk about a rough start.

The Marriage That Wasn't Really a Marriage

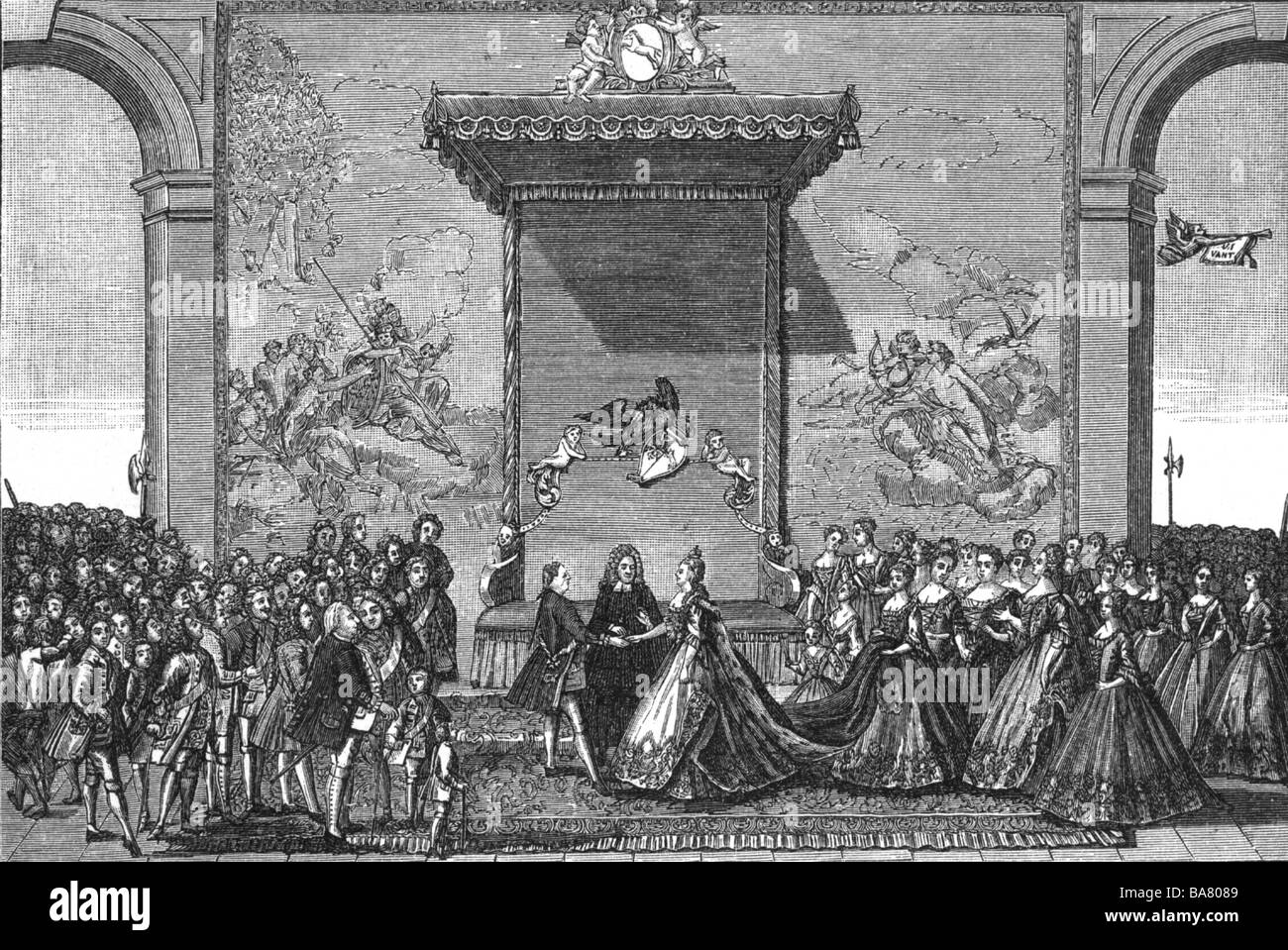

They got married in 1733. For a few years at Rheinsberg Palace, things were actually... okay? Elisabeth Christine later called this time the happiest of her life. They lived like a normal aristocratic couple, or at least a version of one. They talked, they had a court, and Frederick was relatively kind. But the second Frederick's father died in 1740, the mask dropped.

He became King, and basically told Elisabeth Christine: "You stay in Berlin. I'm going to Potsdam."

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

He gave her Schönhausen Palace as a summer residence and told her to handle the "boring" parts of being a Queen—the receptions, the etiquette, the foreign ambassadors. Meanwhile, he built Sanssouci, a palace where women were famously not allowed. Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern never even stepped foot in Sanssouci while Frederick was there. Can you imagine? Your husband has a world-famous palace just a few miles away and you're banned from the guest list.

Why Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern Was the Real Power in Berlin

While Frederick was away for years during the Seven Years' War, Elisabeth Christine became the face of the monarchy. She didn't just sit around and mope. She was remarkably pious and took her duties seriously. When the Russians and Austrians were literally at the gates of Berlin, she was the one who organized the evacuation of the court to Magdeburg.

The people loved her.

They saw her as the "Mother of the State." She spent a huge chunk of her personal allowance on charities. We’re talking about real, boots-on-the-ground help for orphans and widows of the war. She also had a massive intellectual life that gets totally ignored. She wrote books on religion and translated French works into German under a pseudonym. She wasn't just some quiet, submissive figure; she was a woman of the Enlightenment who just happened to be married to a man who didn't want a wife.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

The Weird Truth About Their "Meetings"

When they did meet, it was awkward. Like, really awkward. They only saw each other at official state functions or family weddings. Frederick would be polite, but cold. There’s a famous story that after the Seven Years' War ended—after six years of not seeing her—Frederick walked up to her and his only comment was: "Madame has become more stout."

Ouch.

Yet, she remained fiercely loyal. She never spoke ill of him. She seemed to genuinely admire his genius, even if he treated her like a piece of furniture he had to keep in the guest room. She even kept a portrait of him and mourned him deeply when he died in 1786.

Life at Schönhausen Palace

Schönhausen became her sanctuary. It was where she could be herself without the shadow of Frederick’s disapproval. She turned it into a center of Berlin society. If you were a foreign diplomat or a traveling noble, you didn't go to Potsdam to see the King (he probably wouldn't see you anyway); you went to Schönhausen to see the Queen.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

- She maintained a strict, traditional court.

- She promoted the silk industry in Prussia by planting mulberry trees.

- She hosted weekly receptions that kept the social fabric of the Kingdom together.

She lived to be 81, which was ancient for the 18th century. She outlived Frederick by eleven years and was treated with massive respect by his successor, her nephew Frederick William II.

What We Can Learn From Her Today

Most history books focus on the "Great" men, but Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern shows the strength it takes to fill a role you never asked for, with a partner who doesn't support you. She found purpose in service and intellect rather than in a romanticized marriage that didn't exist.

If you're ever in Berlin, you should actually go visit Schönhausen Palace. It’s one of the few places where her spirit still feels present. It’s not as flashy as Sanssouci, but it feels more human. It tells a story of resilience that’s honestly more impressive than winning a battle.

To get the full picture of this era, you should look into:

- The Memoirs of Wilhelmine of Bayreuth: Frederick’s sister gives a very blunt look at how messy this family really was.

- Schönhausen Palace Museum: They have preserved her apartments, and you can see the actual environment she created for herself.

- Frederick’s Will: He actually left her a significant amount of money and ordered that she be treated with the highest honor after his death, proving that while he didn't love her, he respected her utility to the state.

Next time you hear about the "Philosopher King," remember the woman who kept his capital running while he was busy thinking. She was more than just a forgotten Queen; she was the glue that held Prussia together when the King was nowhere to be found.