You probably learned the standard version in grade school. Eli Whitney, a clever Northerner, invents a machine in 1793 that pulls seeds out of cotton. It was supposed to make life easier. Instead, it accidentally supercharged the slave economy and paved the direct path to the Civil War. It's one of those historical "oops" moments that fundamentally reshaped the planet.

But honestly? The real story is a lot messier. It involves patent lawsuits, industrial espionage, and a guy who ended up making his real fortune selling muskets to the government because his "big idea" was stolen by basically everyone with a hammer and a piece of wood.

The cotton gin by Eli Whitney wasn't just a gadget. It was the moment the South stopped being a struggling agricultural region and started being an economic juggernaut fueled by "White Gold."

How the Cotton Gin Actually Worked (And Why It Mattered)

Before the 1790s, the American South was in a bit of a slump. Tobacco was wearing out the soil. Rice and indigo were niche. Long-staple cotton was easy to process but only grew on the coast. The "green seed" short-staple cotton could grow anywhere, but it was a total nightmare to clean.

Imagine spending an entire day—sunrise to sunset—picking tiny, sticky green seeds out of a single pound of lint. That was the reality. It was slow. It was expensive. It made large-scale production totally pointless.

Then comes Whitney. He was a Yale graduate who headed south to Georgia to be a tutor. While staying at Mulberry Grove, a plantation owned by Catherine Greene (the widow of Revolutionary War General Nathanael Greene), he heard the local planters complaining about the seed problem.

He built a prototype in about ten days.

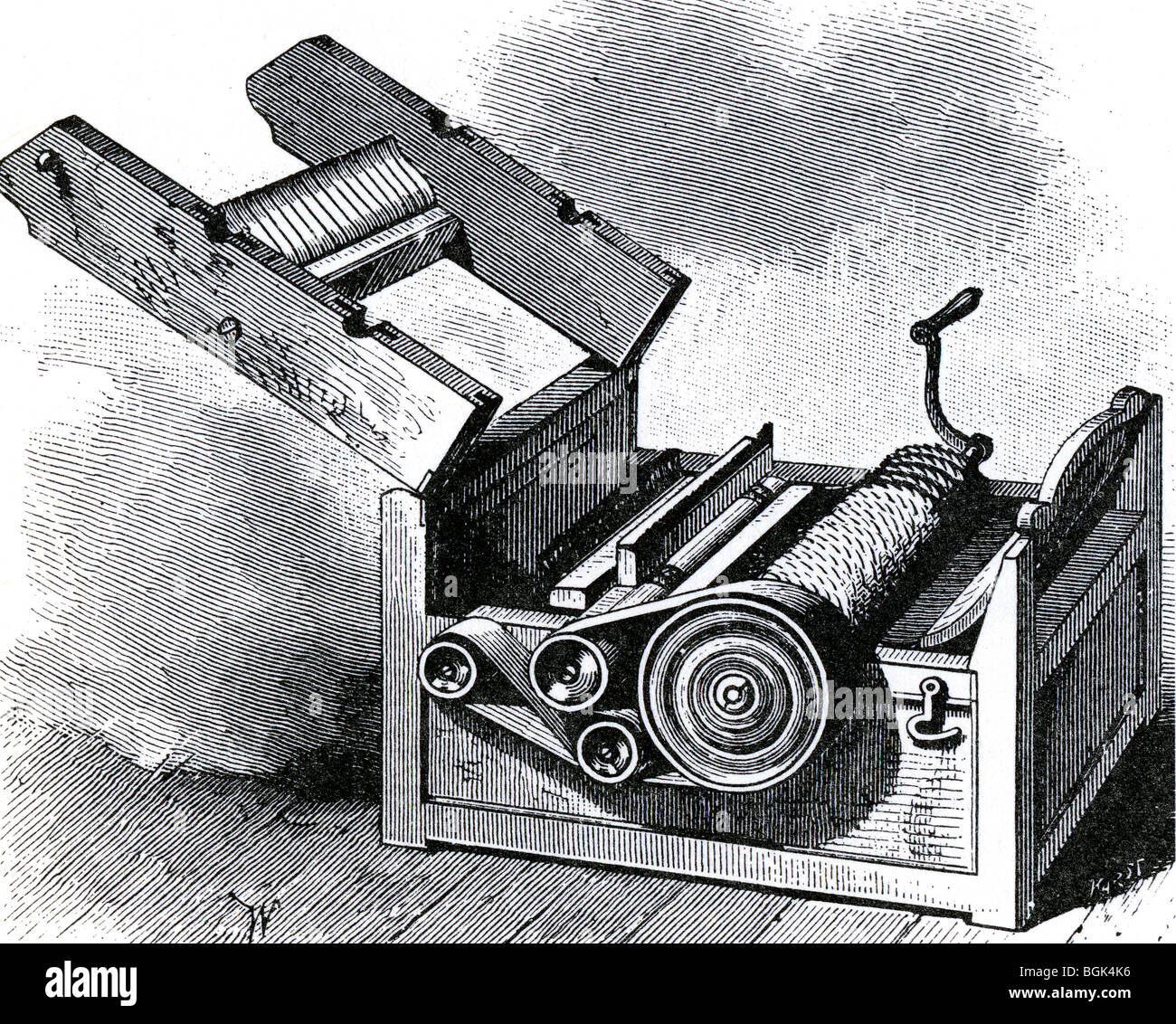

The design was deceptively simple. You had a wooden drum with hooks (later wire teeth) that pulled the cotton fibers through a mesh screen. The seeds were too big to fit through the slots, so they just fell away. A rotating brush then swept the clean lint off the hooks.

It worked. Boy, did it work.

💡 You might also like: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

Suddenly, a single person could process 50 pounds of cotton in a day. That’s a 50-fold increase in productivity. Just like that, the bottleneck was gone.

The Patent Nightmare That Broke Whitney

If you think modern tech companies are bad with patent wars, you should've seen 1794. Whitney and his partner, Phineas Miller, made a massive tactical error. Instead of selling the machines, they tried to charge a "tax" on planters. They wanted one-third of all the cotton produced by their machines.

Planters hated this. It felt like extortion.

Because the cotton gin by Eli Whitney was basically a wooden box with some metal bits, it was incredibly easy to copy. Local blacksmiths started churning out "pirated" gins. Whitney spent years in court trying to protect his intellectual property. By the time he actually won a major suit in 1807, his patent was almost expired, and the South was already flooded with clones.

He famously wrote, "An invention can be so valuable as to be worthless to the inventor." He wasn't kidding. He barely broke even on the gin after legal fees.

The Evolution of the Design

It’s worth noting that Whitney wasn't the only one tinkering. Many historians, including those at the Smithsonian, point out that Catherine Greene likely suggested the use of the brush to clear the lint. Some also argue that enslaved people on the plantation, who had the most experience with the cotton, might have contributed ideas to the design.

Later, a guy named Hodgen Holmes improved the design by replacing Whitney's wire teeth with circular saw blades. This "saw gin" became the industry standard because it was even more efficient. Whitney sued him, too. It was a mess.

The Dark Side: How Technology Fueled Slavery

We can't talk about the cotton gin by Eli Whitney without talking about the human cost. Before 1793, slavery was actually on a slight decline in some parts of the U.S. Some founders thought it might just fade away because it wasn't profitable enough.

📖 Related: Frontier Mail Powered by Yahoo: Why Your Login Just Changed

The gin changed the math.

With the ability to process massive amounts of cotton, planters needed more land and more labor to grow it. Cotton production doubled every decade after the invention. By the mid-1800s, the U.S. was providing 75% of the world's cotton.

This created an insatiable demand for enslaved labor. The "internal slave trade" exploded, forcibly moving over a million people from the Upper South (like Virginia) to the "Cotton Kingdom" in the Deep South (Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana).

The machine was efficient, but the system it supported was brutal. It’s a classic example of how a "labor-saving" device can actually lead to more labor if the goal is infinite growth.

Beyond the Gin: Whitney’s Real Legacy

Whitney didn't stay depressed about his lost cotton profits forever. He took what he learned about mass production and applied it to something else: guns.

He got a government contract to produce 10,000 muskets. At the time, every gun was handmade by a master smith. If a screw broke on your rifle, you couldn't just buy a replacement; a smith had to custom-forge a new one.

Whitney championed the idea of interchangeable parts.

He showed up in Washington and allegedly laid out the parts of ten different guns, scrambled them, and reassembled them in front of President John Adams. While he actually cheated a bit (the parts weren't as "interchangeable" as he claimed, and he hand-fitted them beforehand), the idea stuck.

👉 See also: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

This concept—standardized parts made by machines—is the foundation of the modern assembly line. It’s the reason you can buy a replacement part for your car today. In a weird way, Whitney is the father of American manufacturing, even if his first big hit was a financial bust for him.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often treat Whitney as a lone genius who had a "Eureka" moment. In reality, he was a guy who saw a mechanical problem and applied basic engineering principles to solve it.

- Did he invent the first gin? Not exactly. "Churka" gins had been used in India for centuries for different types of cotton. Whitney's innovation was specifically for the sticky green-seed cotton of the American interior.

- Did he get rich off the gin? Nope. He made his money in firearms.

- Was the gin a "Northern" plot? Some Southerners claimed it was, but the Southern economy leaned into it with everything they had.

Why We Still Study This Today

The cotton gin by Eli Whitney is the ultimate case study in unintended consequences. Technology is never neutral. It interacts with the politics, economics, and social structures of the time.

Whitney thought he was solving a tedious manual labor problem. He ended up cementing an institution that would tear the country apart sixty years later. It’s a reminder that when we "disrupt" an industry, we don't always know where the pieces will land.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're digging into this topic for a project or just because you're a nerd for industrial history, here are a few ways to get a deeper look at the real Whitney:

Check the Primary Sources

The Eli Whitney Papers at Yale University are the gold standard. They contain his actual letters complaining about "pirates" stealing his designs. Reading his own frustration makes the history feel a lot more human.

Look Beyond the Textbook

Visit the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop in Hamden, Connecticut. They focus heavily on his later work with interchangeable parts and the development of the milling machine, which is arguably more important to modern technology than the gin itself.

Analyze the Economic Data

To see the true impact, look at the "Cotton Map" of the 1850s (often called the "Slave Map"). You can see a direct geographic correlation between where the cotton gin made the crop viable and where the highest density of enslaved populations lived. It’s a sobering visual of technology’s footprint.

Evaluate Modern Parallels

Think about how current technologies, like AI, are following similar paths—solving a bottleneck (like data processing) while creating massive, unforeseen shifts in how we live and work. Whitney’s story isn't just about 18th-century wood and wire; it's about the friction between innovation and society.

The legacy of the cotton gin is woven into the very fabric of the United States. It built the wealth of the South, powered the textile mills of the North and England, and forced a reckoning with the country's greatest moral failure. All from a simple box of wire teeth and brushes.