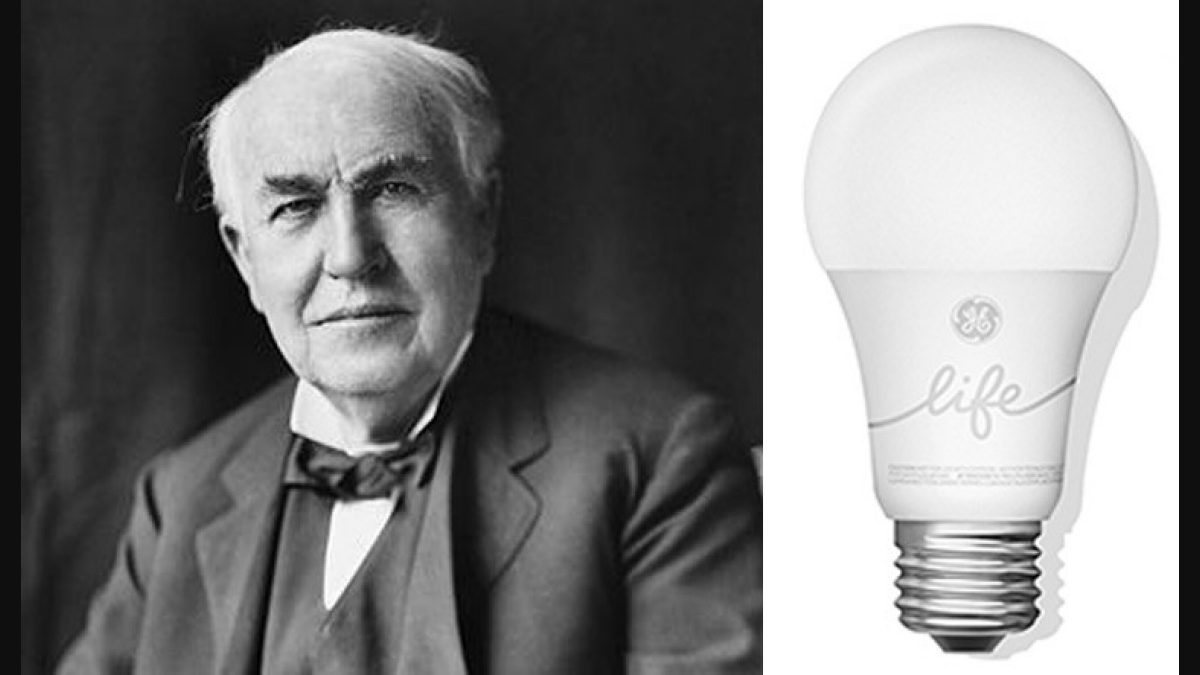

Honestly, if you ask a random person on the street about the electric bulb who invented it, they’ll shout "Thomas Edison" before you even finish the sentence. It’s the standard answer. It's in the history books. But history is usually a bit more chaotic than a third-grade textbook lets on. The reality is that Edison didn't just wake up one day, have a literal lightbulb moment, and save the world from darkness. He was actually standing on the shoulders of about twenty different inventors who had been messing around with glowing wires for over seventy years.

By the time Edison got his patent in 1879, the "idea" of electric light was already old news. People were tired of smelling like kerosene. They hated the dim, flickering, fire-hazard mess of gas lamps. The world was desperate for a clean, reliable glow. But making it happen? That was the hard part. It wasn't just about making a light; it was about making a light that didn't burn out in ten minutes or cost a fortune to run.

The 70-Year Head Start

Let’s go back to 1802. That’s nearly eighty years before Edison’s big breakthrough. A guy named Humphry Davy—an English chemist with a penchant for dangerous experiments—created the first electric light. He hooked up a bunch of batteries to two charcoal sticks and created an "arc" of light. It was blindingly bright. It was also completely useless for a living room because it sizzled, hissed, and burned out almost instantly.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Panasonic portable DVD player still has a cult following in 2026

Then came Warren de la Rue in 1840. He had a brilliant idea: use platinum. Since platinum has an incredibly high melting point, he figured it could handle the heat. He put a platinum filament in a vacuum tube and passed an electric current through it. It worked! Sorta. The problem was that platinum is insanely expensive. Unless you were a billionaire in the mid-1800s, a De la Rue bulb wasn't happening in your house.

So, when we talk about electric bulb who invented, we have to mention Joseph Swan. This is where the drama gets real. Swan, another Englishman, was working on this at the exact same time as Edison. In fact, Swan had a working prototype using carbonized paper filaments well before Edison did. He even lit up his own house and a library in Newcastle.

Edison’s Real Genius Wasn't the Bulb

Edison wasn't just an inventor; he was a relentless optimizer. He was the guy who stayed up all night at Menlo Park, testing thousands of different materials to see what would last. He tried coconut hair. He tried fishing line. He reportedly tested over 6,000 different vegetable fibers.

The Bamboo Breakthrough

In 1879, Edison’s team finally found that a carbonized cotton thread could last for about 13.5 hours. Not bad, but not enough to change the world. The real "eureka" moment happened when they tried carbonized bamboo. Specifically, a certain type of bamboo from Japan. That filament lasted for over 1,200 hours.

That was the game-changer.

But here’s the thing: Swan was suing him. Instead of fighting a decades-long legal battle that would have bankrupted both of them, they did something very modern. They merged. They formed "Ediswan," a company that dominated the British market. It’s a classic example of how business often matters more than the initial spark of creativity.

Why Everyone Forgets the Others

We love a lone wolf story. We want to believe in the singular genius in a lab coat. But the electric bulb who invented narrative is actually a story of infrastructure. Edison won the history books because he didn't just invent the bulb; he invented the grid.

He realized that a lightbulb is a paperweight if you don't have a way to get electricity into the house. He designed the wiring, the meters, the switches, and the power stations. He created the Pearl Street Station in New York, the first central power plant. He turned light into a utility.

🔗 Read more: How to Actually Get Spotify Premium Free 3 Months Without the Usual Hassle

Meanwhile, guys like Hiram Maxim (who later invented the machine gun) were also claiming they had the "real" lightbulb first. Maxim was bitter about it for the rest of his life. He felt Edison had cheated him out of his legacy through better marketing and faster patent filings. And he might have been right. But in the world of technology, being first is often less important than being the one who makes it scalable.

The Vacuum Problem

One of the biggest hurdles wasn't the filament at all. It was the air. If you have oxygen inside the bulb, the filament catches fire and disappears. You need a near-perfect vacuum. Hermann Sprengel invented the mercury vacuum pump in 1865. Without that specific piece of German engineering, neither Swan nor Edison would have succeeded. It’s these tiny, "boring" inventions that actually make the big ones possible.

The Tungsten Shift

If you look at an old-school incandescent bulb today, it doesn't use bamboo. It uses tungsten. Why? Because tungsten is tough. It has the highest melting point of any element in its pure form.

- 1904: A Hungarian company called Tungsram starts using tungsten.

- 1910: William David Coolidge at General Electric figures out how to make tungsten "ductile" (stretchy), so it can be made into thin wires.

- 1913: Irving Langmuir finds out that filling the bulb with an inert gas like argon prevents the tungsten from evaporating too fast.

This is the version of the bulb that survived for a century. It's the one that got hot to the touch and wasted about 90% of its energy as heat. We used it anyway because it was cheap and the light felt "warm."

The Modern Pivot: LED and Beyond

We’ve moved past the filament entirely now. The electric bulb who invented question has a new chapter: the LED (Light Emitting Diode). Nick Holonyak Jr. invented the first practical visible-spectrum LED in 1962 while working for GE. He called it the "magic one."

Unlike Edison's bulb, LEDs don't have a filament to burn out. They move electrons through a semiconductor material. It’s essentially a computer chip that glows. This is why your "bulb" now lasts 25,000 hours instead of 1,000. It’s also why we can have smart bulbs that change color to "Arctic Aurora" or "Sunset" with a tap on a phone.

The Dark Side of Innovation

There’s a weird bit of history called the Phoebus Cartel. In 1924, the major lightbulb manufacturers (including GE and Osram) got together and decided to intentionally shorten the lifespan of bulbs to 1,000 hours. Before this, some bulbs lasted much longer. They realized that if a bulb lasted forever, they’d go out of business. It’s one of the earliest documented cases of "planned obsolescence."

There is actually a bulb called the Centennial Light in Livermore, California. It has been burning almost continuously since 1901. It’s a hand-blown bulb with a carbon filament, and it proves that the technology to make things last has existed for over a century—we just chose not to use it for economic reasons.

Key Takeaways for the Curious

If you’re trying to wrap your head around the timeline, stop looking for a single date. It’s a progression.

- 1802: Humphry Davy creates the Arc Lamp (too bright, too fast).

- 1840: Warren de la Rue uses platinum (too expensive).

- 1878: Joseph Swan gets a UK patent for a carbon filament bulb.

- 1879: Thomas Edison finds the right vacuum and bamboo combo for a commercial product.

- 1900s: The shift to tungsten makes bulbs durable.

- 1960s-Present: The LED revolution makes filaments obsolete.

What You Should Do Next

If you’re interested in the history of tech, don't just stop at the lightbulb. Look into the "War of Currents" between Edison and Nikola Tesla. It explains why our houses use Alternating Current (AC) instead of the Direct Current (DC) Edison fought so hard for.

You can also check your own home. Most people are still using "warm white" LEDs that mimic Edison’s old carbon glow. If you want better sleep, try switching to bulbs that allow you to adjust the "color temperature" (measured in Kelvins). Lower Kelvins (2700K) are better for the evening, while higher Kelvins (5000K) are great for productivity during the day.

History isn't a straight line. It's a bunch of people in messy labs, suing each other, failing thousands of times, and eventually—luckily—finding something that glows.