You've probably seen the maps. Those jagged, red-and-blue charts that pop up every four years, claiming to show how "tilted" the playing field is. They’re everywhere on social media and cable news. Usually, they’re used to argue that one party is getting a raw deal. But if you actually look at an electoral college bias chart from a data science perspective, the story is way messier—and more interesting—than just "small states have too much power."

Honestly, most people treat these charts like a fixed property of the Constitution. It's not.

Bias in the Electoral College is a moving target. It shifts based on how populations move, who shows up to vote, and where the "tipping point" state actually lands. In 2020, the system had a massive lean toward the GOP. In 2024? That lean basically evaporated. If you want to understand why the 2024 election didn't match the "Republican Lock" narrative, you have to look at how the efficiency of the vote changed.

What is an Electoral College Bias Chart Anyway?

Basically, political scientists use these charts to measure "partisan bias."

👉 See also: Finding Obituaries in Lawrence County: What Most People Get Wrong

Think of it this way: if both the Democrat and the Republican got exactly 50% of the national popular vote, who would win the most electoral votes? In a perfectly "fair" system, they’d both get 269. But we don't live in that world. A bias chart tracks the "tipping point" state—the one that gives the winner their 270th electoral vote—and compares it to the national average.

If the tipping point state is 3 points more Republican than the country as a whole, the chart shows a +3 GOP bias.

Why the "Small State" Argument is Sorta Wrong

Everyone blames the two extra electoral votes every state gets for their Senators. People say Wyoming has "more power" than California. Technically, yeah, a vote in Wyoming counts for more "electoral juice" because of the math. But experts like those at the University of Chicago’s Center for Effective Government have found that this isn't actually what drives the bias.

The real culprit? Winner-take-all.

When a candidate wins California by 5 million votes, those 5 million extra votes are "wasted." They don't help win Pennsylvania or Michigan. Because Democrats tend to cluster in massive margins in deep blue states, they "waste" more votes. That’s the engine behind the bias. It’s not about the size of the state; it’s about the efficiency of the margin.

The 2024 Shift: When the Bias Disappeared

For years, the electoral college bias chart looked like a steep climb for Democrats. In 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency while losing the popular vote by 2.1 points. In 2020, Joe Biden won the popular vote by 4.5 points but only narrowly carried the tipping point state (Wisconsin) by 0.6 points.

That was a nearly 4-point Republican bias. Massive.

But then 2024 happened. According to data from Sabato’s Crystal Ball and the Cook Political Report, that bias hit a wall. Donald Trump didn't just win the Electoral College; he won the popular vote by about 1.5 points. More importantly, the tipping point state—Pennsylvania—voted almost exactly like the rest of the country.

When the tipping point state matches the national popular vote, the bias is zero.

What caused the 2024 alignment?

- Democratic "Efficiency" Improved: Not because they won more voters, but because they lost them in the "right" places. Trump made huge gains in New York, California, and New Jersey. Those gains didn't win him those states, but they shrunk the Democratic margins.

- The Tipping Point Moved: Pennsylvania became the center of the universe. Because it stayed closer to the national average than Wisconsin did in 2020, the "tilt" of the map flattened out.

- Urban-Rural Flattening: In some ways, the country became more uniform. When the "Red" areas get a little less Red and "Blue" areas get significantly less Blue, the map starts to look more like the national total.

How to Read a Bias Chart Like an Expert

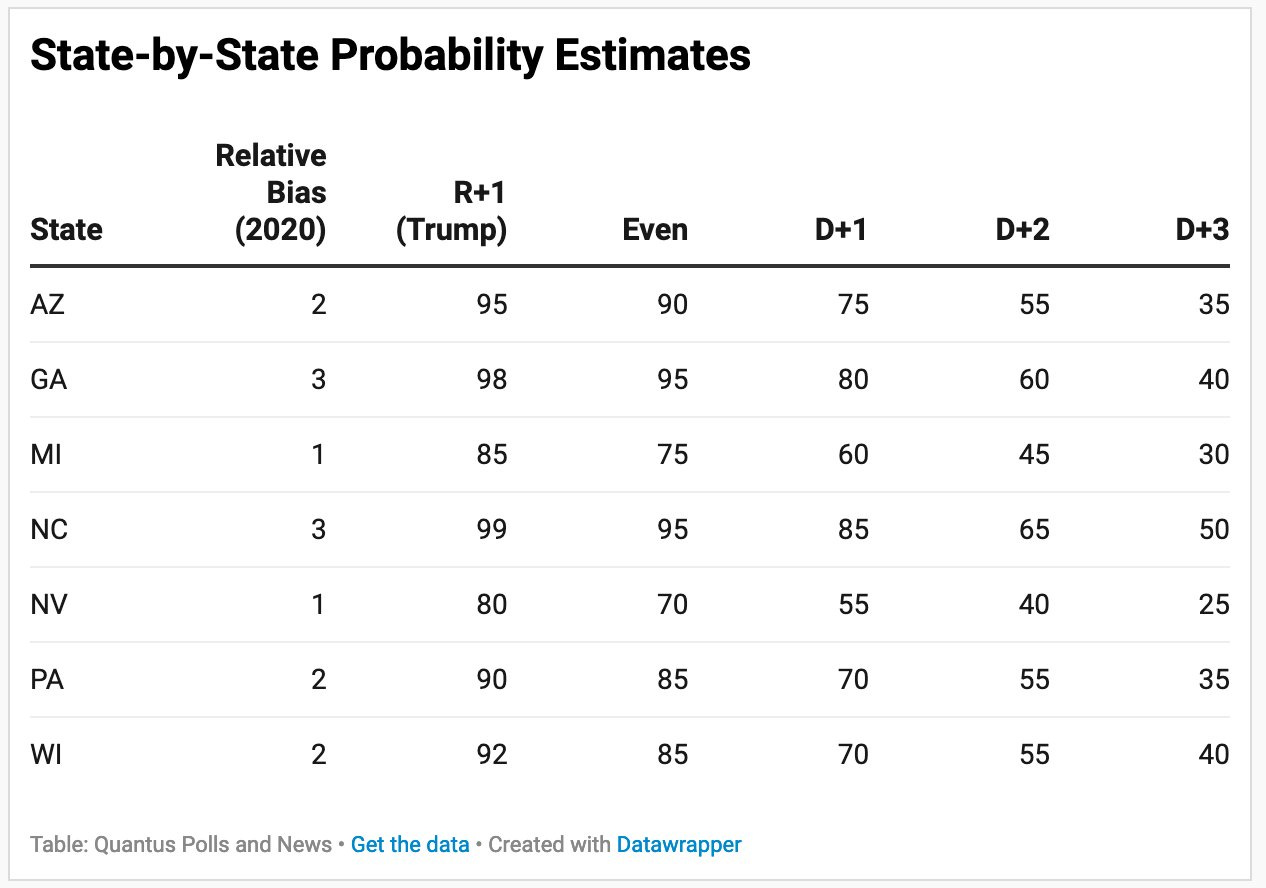

If you're looking at a chart from Nate Silver’s Silver Bulletin or FiveThirtyEight, don't just look at the win probabilities. Look at the "Chances of a Split."

A split is when one person wins the popular vote and the other wins the Electoral College. In 2020, the charts showed a very high chance of a split favoring Trump. In 2024, those same charts showed the split chance dropping as the campaign went on.

Key Indicators to Watch:

- State vs. National Margin: If the swing states are polling 2 points to the right of the national polls, the map is biased toward Republicans.

- The "Blue Wall" Correlation: Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin usually move together. If they break away from the national trend, the bias chart will spike.

- Third-Party Impact: In 1992 and 1996, Ross Perot scrambled the math so much that the traditional bias charts almost broke. Third parties "eat" votes that would otherwise contribute to a party's efficiency.

The Future of the "GOP Lock"

Is the Republican advantage gone for good? Kinda, but maybe not.

Politics is fluid. The electoral college bias chart is just a snapshot of a specific moment in time. If Democrats continue to lose ground with Hispanic voters and working-class voters in big cities, their "wasted vote" problem might actually go away. If you win a state like New York by 10 points instead of 30, your national popular vote total drops, but your Electoral College standing stays the same.

That’s the irony of 2024. The GOP’s success in "Blue" territory actually made the Electoral College look "fairer" by traditional metrics.

Actionable Insights for Following the Map

If you want to stay ahead of the curve for the next cycle, stop obsessing over national polls. They're fun for headlines, but they don't tell you about the map's tilt.

Focus on the "Deviation" instead. Check sources like Cook Political Report’s PVI (Partisan Voting Index). If a swing state’s PVI is moving closer to even (0.0), the Electoral College bias is shrinking. If it's moving further away, prepare for another year where the popular vote winner might lose the White House.

Keep an eye on Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) movements too. As the American Bar Association noted in their 2025 updates, more states are looking at RCV and nonpartisan primaries. If these reforms take hold, the way we calculate "bias" will have to change entirely because the winner-take-all math gets disrupted.

Don't let a single chart freak you out. The map isn't destiny; it's just a reflection of where we're standing right now.

Next Steps for Tracking Election Trends:

- Monitor the Cook PVI updates for 2026 to see if swing states are becoming more or less "extreme" relative to the national average.

- Check the State Level Deviation charts on Sabato's Crystal Ball to see which regions are "de-aligning" from their traditional party bases.

- Look for updates on the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which currently has 17 states (plus D.C.) signed on, to see if the Electoral College itself is heading for a legal overhaul.